2001 AIME I Problems/Problem 6

Problem

A fair die is rolled four times. The probability that each of the final three rolls is at least as large as the roll preceding it may be expressed in the form ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are relatively prime positive integers. Find

are relatively prime positive integers. Find ![]() .

.

Contents

Solutions

Solution 1

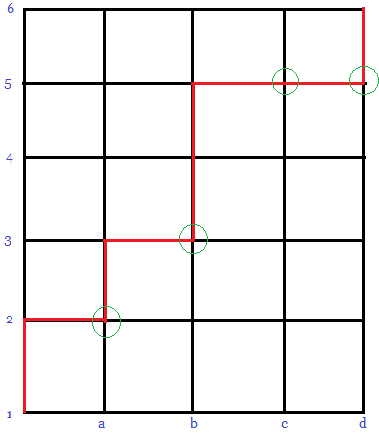

Recast the problem entirely as a block-walking problem. Call the respective dice ![]() . In the diagram below, the lowest

. In the diagram below, the lowest ![]() -coordinate at each of

-coordinate at each of ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() corresponds to the value of the roll.

corresponds to the value of the roll.

The red path corresponds to the sequence of rolls ![]() . This establishes a bijection between valid dice roll sequences and block walking paths.

. This establishes a bijection between valid dice roll sequences and block walking paths.

The solution to this problem is therefore ![]() . So the answer is

. So the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 2

If we take any combination of four numbers, there is only one way to order them in a non-decreasing order. It suffices now to find the number of combinations for four numbers from ![]() . We can visualize this as taking the four dice and splitting them into 6 slots (each slot representing one of {1,2,3,4,5,6}), or dividing them amongst 5 separators. Thus, there are

. We can visualize this as taking the four dice and splitting them into 6 slots (each slot representing one of {1,2,3,4,5,6}), or dividing them amongst 5 separators. Thus, there are  outcomes of four dice. The solution is therefore

outcomes of four dice. The solution is therefore ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Solution 3

Call the dice rolls ![]() . The difference between the

. The difference between the ![]() and

and ![]() distinguishes the number of possible rolls there are.

distinguishes the number of possible rolls there are.

- If

, then the values of

, then the values of  are set, and so there are

are set, and so there are  values for

values for  .

. - If

, then there are

, then there are  ways to arrange for values of

ways to arrange for values of  , but only

, but only  values for

values for  .

. - If

, then there are

, then there are  ways to arrange

ways to arrange  , and there are only

, and there are only  values for

values for  .

.

Continuing, we see that the sum is equal to  . The requested probability is

. The requested probability is ![]() .

.

Solution 4

The dice rolls can be in the form

ABCD

AABC

AABB

AAAB

AAAA

where A, B, C, D are some possible value of the dice rolls. (These forms are not keeping track of whether or not the dice are in ascending order, just the possible outcomes.)

- Now, for the first case, there are

ways for this. We do not have to consider the order because the combination counts only one of the permutations; we can say that it counts the correct (ascending order) permutation.

ways for this. We do not have to consider the order because the combination counts only one of the permutations; we can say that it counts the correct (ascending order) permutation. - Second case:

ways to pick 3 numbers,

ways to pick 3 numbers,  ways to pick 1 of those 3 to duplicate. A total of 60 for this case.

ways to pick 1 of those 3 to duplicate. A total of 60 for this case. - Third case:

ways to pick 2 numbers. We will duplicate both, so nothing else in this case matters.

ways to pick 2 numbers. We will duplicate both, so nothing else in this case matters. - Fourth case:

ways to pick 2 numbers. We pick one to duplicate with

ways to pick 2 numbers. We pick one to duplicate with  , so there are a total of 30 in this case.

, so there are a total of 30 in this case. - Fifth case:

; all get duplicated so nothing else matters.

; all get duplicated so nothing else matters.

There are a total of ![]() possible dice rolls.

possible dice rolls.

Thus,

Solution 5

Consider the number of possible dice roll combinations which work after ![]() roll, after

roll, after ![]() rolls, and so on. There is 6 possible rolls for the first dice. If the number rolled is a 1, then there are 6 further values that are possible for the second dice; if the number rolled is a 2, then there are 5 further values that are possible for the second dice, and so on.

rolls, and so on. There is 6 possible rolls for the first dice. If the number rolled is a 1, then there are 6 further values that are possible for the second dice; if the number rolled is a 2, then there are 5 further values that are possible for the second dice, and so on.

Suppose we generalize this as a function, say ![]() return the number of possible combinations after

return the number of possible combinations after ![]() rolls and

rolls and ![]() being the beginning value of the first roll. It becomes clear that from above,

being the beginning value of the first roll. It becomes clear that from above, ![]() ; every value of

; every value of ![]() after that is equal to the sum of the number of combinations of

after that is equal to the sum of the number of combinations of ![]() rolls that have a starting value of at least

rolls that have a starting value of at least ![]() . If we slowly count through and add up all the possible combinations we get

. If we slowly count through and add up all the possible combinations we get ![]() possibilities.

possibilities.

Solution 6

In a manner similar to the above solution, instead consider breaking it down into two sets of two dice rolls. The first subset must have a maximum value which is ![]() the minimum value of the second subset.

the minimum value of the second subset.

- If the first subset ends in a 1, there is

such subset and there are

such subset and there are  ways of making the second subset.

ways of making the second subset. - If the first subset ends in a 2, there is

such subsets and there are

such subsets and there are  ways of making the second subset.

ways of making the second subset.

Thus, the number of combinations is  , and the probability again is

, and the probability again is ![]() , giving

, giving ![]() .

.

Solution 7 Recursion Formula

If you're too tired to think about any of the above smart transformations of the problem, a recursion formula can be a robust way to the correct answer.

We just need to work out the valid cases for each roll. Denote by ![]() the number of valid cases in the

the number of valid cases in the ![]() -th roll when the number

-th roll when the number ![]() is rolled, for

is rolled, for ![]() and

and ![]() . Then we have the following recursion formula:

. Then we have the following recursion formula:

![]()

![]()

![]() The logic is that, if

The logic is that, if ![]() is rolled, then the number of valid cases is the subtotal of valid cases in the preceding roll for the outcome of 1 to

is rolled, then the number of valid cases is the subtotal of valid cases in the preceding roll for the outcome of 1 to ![]() . The recursion can be easily calculated by hand when

. The recursion can be easily calculated by hand when ![]() are put in columns side by side, given the fact that te numbers are smaller than 100.

Finally, the total number of cases is

are put in columns side by side, given the fact that te numbers are smaller than 100.

Finally, the total number of cases is

![\[N = \sum_{n=1}^{6} N_{3}(n)\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/f/2/1/f21df1f4507d3651ff4cdf7475e42fd760a937c8.png) and

and

![]()

Solution 8

We use expected value.

The first dice averages to ![]() . So, we start off with

. So, we start off with ![]() . Now, we have a

. Now, we have a ![]() chance.

chance.

Next, we consider the number that we picked. There is a total of ![]() for the probabilities when we pick

for the probabilities when we pick ![]() ,

, ![]() , or

, or ![]() . So, we get

. So, we get ![]() . Finally, we have

. Finally, we have ![]() and

and ![]() . This gives

. This gives ![]() . Multiplying, we get

. Multiplying, we get ![]() .

~asdf334

(I actually don't know if this is a valid sol, it seems sketchy to me lol)

.

~asdf334

(I actually don't know if this is a valid sol, it seems sketchy to me lol)

Solution 9: Observation of each case

Lets try casework and observe the cases. Notice that if the last roll is a ![]() , then the only dice rolls may be

, then the only dice rolls may be ![]() , which is only

, which is only ![]() possibility. Observe that if the last roll is

possibility. Observe that if the last roll is ![]() , then there are

, then there are ![]() possibilities. When the last roll is a

possibilities. When the last roll is a ![]() , there are

, there are ![]() possibilities. Notice when the last roll is

possibilities. Notice when the last roll is ![]() , the number of cases is the sum of the first

, the number of cases is the sum of the first ![]() positive triangular numbers. This is easily provable when observing the numbers of possibilities after assigning a value to the last and second to last rolls.

So there are a total of

positive triangular numbers. This is easily provable when observing the numbers of possibilities after assigning a value to the last and second to last rolls.

So there are a total of ![]() possibilities. So the probability is

possibilities. So the probability is ![]() and

and ![]() . ~skyscraper

. ~skyscraper

Solution 10: Distributions

This is equivalent to picking a four-element sequence of ![]() with repetition. Notice that once the sequence is picked, there is one and only one way to order these so that they form a sequence of rolls satisfying our conditions.

with repetition. Notice that once the sequence is picked, there is one and only one way to order these so that they form a sequence of rolls satisfying our conditions.

Now count the number of such four-element sequences, let ![]() be the number of

be the number of ![]() s in the sequence,

s in the sequence, ![]() be the number of

be the number of ![]() s,

s, ![]()

![]() s,

s, ![]()

![]() s,

s, ![]()

![]() s, and

s, and ![]()

![]() s. Now we see that we must have

s. Now we see that we must have ![]() with

with ![]() being nonnegative integers since there are a total of

being nonnegative integers since there are a total of ![]() numbers picked. The number of solutions to this is

numbers picked. The number of solutions to this is ![]() so our total number is equal to

so our total number is equal to ![]() making our answer

making our answer ![]()

~Ilikeapos

Solution 11: The proof no one will read

We can construct a bijection using stars and bars as follows:

Consider the sequence of ![]() balls

balls ![]() . Now place

. Now place ![]() bars in between them. For instance, the configuration

bars in between them. For instance, the configuration ![]() represents the rolls

represents the rolls ![]() . Now you might think, "Oh now it's easy.

. Now you might think, "Oh now it's easy. ![]() ." However, what if we have

." However, what if we have ![]() ? Maybe we could remove the last ball. But then we have

? Maybe we could remove the last ball. But then we have ![]() balls. How do we rid of this ambiguity? Well we could give it a value. If there is nothing to the right of a bar, give it the value of

balls. How do we rid of this ambiguity? Well we could give it a value. If there is nothing to the right of a bar, give it the value of ![]() . Now the answer is simple.

. Now the answer is simple.  . Then we have

. Then we have ![]() different rolls, and now, the answer is simply

different rolls, and now, the answer is simply ![]() , which gives the answer of

, which gives the answer of ![]() . (Remember to always include the

. (Remember to always include the ![]() in this competition for

in this competition for ![]() or

or ![]() digit numbers).

digit numbers).

~th1nq3r

See also

| 2001 AIME I (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 5 |

Followed by Problem 7 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.

ways to arrange for values of

ways to arrange for values of  ways to arrange

ways to arrange  ways for this. We do not have to consider the order because the combination counts only one of the permutations; we can say that it counts the correct (ascending order) permutation.

ways for this. We do not have to consider the order because the combination counts only one of the permutations; we can say that it counts the correct (ascending order) permutation. ways to pick 3 numbers,

ways to pick 3 numbers,  ways to pick 2 numbers. We will duplicate both, so nothing else in this case matters.

ways to pick 2 numbers. We will duplicate both, so nothing else in this case matters. ways to pick 2 numbers. We pick one to duplicate with

ways to pick 2 numbers. We pick one to duplicate with  , so there are a total of 30 in this case.

, so there are a total of 30 in this case. ; all get duplicated so nothing else matters.

; all get duplicated so nothing else matters.