2024 AIME II Problems/Problem 12

Contents

- 1 Problem

- 2 Solution 1 (completely no calculus required)

- 3 Solution 2

- 4 Solution 3

- 5 Solution 4 (coordinate bash)

- 6 Solution 5 (small perturb)

- 7 Solution 6(trig identities and questionable rigidity)

- 8 Solution 7

- 9 Solution 8 (intuitive elementary calculus solution)

- 10 Video Solution

- 11 Video Solution

- 12 Query

- 13 See also

Problem

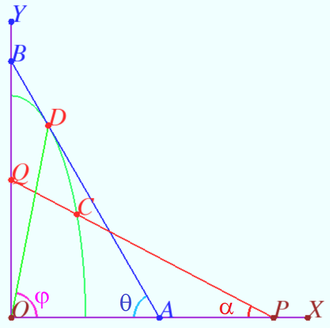

Let \(O=(0,0)\), \(A=\left(\tfrac{1}{2},0\right)\), and \(B=\left(0,\tfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\) be points in the coordinate plane. Let \(\mathcal{F}\) be the family of segments \(\overline{PQ}\) of unit length lying in the first quadrant with \(P\) on the \(x\)-axis and \(Q\) on the \(y\)-axis. There is a unique point \(C\) on \(\overline{AB}\), distinct from \(A\) and \(B\), that does not belong to any segment from \(\mathcal{F}\) other than \(\overline{AB}\). Then \(OC^2=\tfrac{p}{q}\), where \(p\) and \(q\) are relatively prime positive integers. Find \(p+q\).

Solution 1 (completely no calculus required)

Begin by finding the equation of the line ![]() :

: ![]() Now, consider the general equation of all lines that belong to

Now, consider the general equation of all lines that belong to ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be located at

be located at ![]() and

and ![]() be located at

be located at ![]() . With these assumptions, we may arrive at the equation

. With these assumptions, we may arrive at the equation ![]() . However, a critical condition that must be satisfied by our parameters is that

. However, a critical condition that must be satisfied by our parameters is that ![]() , since the length of

, since the length of ![]() .

.

Here's the golden trick that resolves the problem: we wish to find some point ![]() along

along ![]() such that

such that ![]() passes through

passes through ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() . It's not hard to convince oneself of this, since the property

. It's not hard to convince oneself of this, since the property ![]() implies that if

implies that if ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

We should now try to relate the point ![]() to some value of

to some value of ![]() . This is accomplished by finding the intersection of two lines:

. This is accomplished by finding the intersection of two lines: ![]()

Where we have also used the fact that ![]() , which follows nicely from

, which follows nicely from ![]() .

. ![]()

Square both sides and go through some algebraic manipulations to arrive at

![]()

Note how ![]() is a solution to this polynomial, and it is logically so. If we found the set of intersections consisting of line segment

is a solution to this polynomial, and it is logically so. If we found the set of intersections consisting of line segment ![]() with an identical copy of itself, every single point on the line (all

with an identical copy of itself, every single point on the line (all ![]() values) should satisfy the equation. Thus, we can perform polynomial division to eliminate the extraneous solution

values) should satisfy the equation. Thus, we can perform polynomial division to eliminate the extraneous solution ![]() .

. ![]()

Remember our original goal. It was to find an ![]() value such that

value such that ![]() is the only valid solution. Therefore, we can actually plug in

is the only valid solution. Therefore, we can actually plug in ![]() back into the equation to look for values of

back into the equation to look for values of ![]() such that the relation is satisfied, then eliminate undesirable answers.

such that the relation is satisfied, then eliminate undesirable answers.

![]() This is easily factored, allowing us to determine that

This is easily factored, allowing us to determine that ![]() . The latter root is not our answer, since on line

. The latter root is not our answer, since on line ![]() ,

, ![]() , the horizontal line segment running from

, the horizontal line segment running from ![]() to

to ![]() covers that point. From this, we see that

covers that point. From this, we see that ![]() is the only possible candidate.

is the only possible candidate.

Going back to line ![]() , plugging in

, plugging in ![]() yields

yields ![]() . The distance from the origin is then given by

. The distance from the origin is then given by  . That number squared is

. That number squared is ![]() , so the answer is

, so the answer is ![]() .

.

~Installhelp_hex

Why this works: Assume the quartic equation has exactly two real roots. Then for ![]() to be the only solution, it must be a doubled root. Thus, even after dividing the quartic by

to be the only solution, it must be a doubled root. Thus, even after dividing the quartic by ![]() ,

, ![]() is still a root.

~inaccessibles

is still a root.

~inaccessibles

Solution 2

![]()

Now, we want to find ![]() . By L'Hôpital's rule, we get

. By L'Hôpital's rule, we get ![]() . This means that

. This means that ![]() , so we get

, so we get ![]() .

.

~Bluesoul

Solution 3

The equation of line ![]() is

is ![]()

The position of line ![]() can be characterized by

can be characterized by ![]() , denoted as

, denoted as ![]() .

Thus, the equation of line

.

Thus, the equation of line ![]() is

is

![]()

Solving (1) and (2), the ![]() -coordinate of the intersecting point of lines

-coordinate of the intersecting point of lines ![]() and

and ![]() satisfies the following equation:

satisfies the following equation:

![]()

We denote the L.H.S. as ![]() .

.

We observe that ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

Therefore, the point

.

Therefore, the point ![]() that this problem asks us to find can be equivalently stated in the following way:

that this problem asks us to find can be equivalently stated in the following way:

We interpret Equation (1) as a parameterized equation that ![]() is a tuning parameter and

is a tuning parameter and ![]() is a variable that shall be solved and expressed in terms of

is a variable that shall be solved and expressed in terms of ![]() .

In Equation (1), there exists a unique

.

In Equation (1), there exists a unique ![]() , denoted as

, denoted as ![]() (

(![]() -coordinate of point

-coordinate of point ![]() ), such that the only solution is

), such that the only solution is ![]() . For all other

. For all other ![]() , there are more than one solutions with one solution

, there are more than one solutions with one solution ![]() and at least another solution.

and at least another solution.

Given that function ![]() is differentiable, the above condition is equivalent to the first-order-condition

is differentiable, the above condition is equivalent to the first-order-condition

![]()

Calculating derivatives in this equation, we get

![\[ - \left( \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3} x_C \right) \frac{\cos 60^\circ}{\sin^2 60^\circ} + x_C \frac{\sin 60^\circ}{\cos^2 60^\circ} = 0. \]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/4/3/a/43a5e2720c57d2a8c604b428074f9242206beb54.png)

By solving this equation, we get

![]()

Plugging this into Equation (1), we get the ![]() -coordinate of point

-coordinate of point ![]() :

:

![]()

Therefore, \begin{align*} OC^2 & = x_C^2 + y_C^2 \\ & = \frac{7}{16} . \end{align*}

Therefore, the answer is ![]() .

.

~Steven Chen (Professor Chen Education Palace, www.professorchenedu.com)

Solution 4 (coordinate bash)

Let ![]() be a segment in

be a segment in ![]() with x-intercept

with x-intercept ![]() and y-intercept

and y-intercept ![]() . We can write

. We can write ![]() as

\begin{align*}

\frac{x}{a} + \frac{y}{b} &= 1 \\

y &= b(1 - \frac{x}{a}).

\end{align*}

Let the unique point in the first quadrant

as

\begin{align*}

\frac{x}{a} + \frac{y}{b} &= 1 \\

y &= b(1 - \frac{x}{a}).

\end{align*}

Let the unique point in the first quadrant ![]() lie on

lie on ![]() and no other segment in

and no other segment in ![]() . We can find

. We can find ![]() by solving

by solving

![]() and taking the limit as

and taking the limit as ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() has length

has length ![]() ,

, ![]() by the Pythagorean theorem. Solving this for

by the Pythagorean theorem. Solving this for ![]() , we get

\begin{align*}

a^2 + b^2 &= 1 \\

b^2 &= 1 - a^2 \\

\frac{db^2}{da} &= \frac{d(1 - a^2)}{da} \\

2a\frac{db}{da} &= -2a \\

db &= -\frac{a}{b}da.

\end{align*}

After we substitute

, we get

\begin{align*}

a^2 + b^2 &= 1 \\

b^2 &= 1 - a^2 \\

\frac{db^2}{da} &= \frac{d(1 - a^2)}{da} \\

2a\frac{db}{da} &= -2a \\

db &= -\frac{a}{b}da.

\end{align*}

After we substitute ![]() , the equation for

, the equation for ![]() becomes

becomes

![]()

In ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . To find the x-coordinate of

. To find the x-coordinate of ![]() , we substitute these into the equation for

, we substitute these into the equation for ![]() and get

\begin{align*}

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}(1 - \frac{x}{\frac{1}{2}}) &= (\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \frac{\frac{1}{2}}{\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}} da)(1 - \frac{x}{\frac{1}{2} + da}) \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}(1 - 2x) &= (\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \frac{da}{\sqrt{3}})(1 - \frac{x}{\frac{1 + 2da}{2}}) \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x &= \frac{3 - 2da}{2\sqrt{3}}(1 - \frac{2x}{1 + 2da}) \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x &= \frac{3 - 2da}{2\sqrt{3}} \cdot \frac{1 + 2da - 2x}{1 + 2da} \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x &= \frac{3 + 6da - 6x - 2da - 4da^2 + 4xda}{2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3}da} \\

(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x)(2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3}da) &= 3 + 6da - 6x - 2da - 4da^2 + 4xda \\

3 + 6da - 6x - 12xda &= 3 + 4da - 6x - 4da^2 + 4xda \\

2da &= -4da^2 + 16xda \\

16xda &= 2da + 4da^2 \\

x &= \frac{da + 2da^2}{8da}.

\end{align*}

We take the limit as

and get

\begin{align*}

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}(1 - \frac{x}{\frac{1}{2}}) &= (\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \frac{\frac{1}{2}}{\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}} da)(1 - \frac{x}{\frac{1}{2} + da}) \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}(1 - 2x) &= (\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \frac{da}{\sqrt{3}})(1 - \frac{x}{\frac{1 + 2da}{2}}) \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x &= \frac{3 - 2da}{2\sqrt{3}}(1 - \frac{2x}{1 + 2da}) \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x &= \frac{3 - 2da}{2\sqrt{3}} \cdot \frac{1 + 2da - 2x}{1 + 2da} \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x &= \frac{3 + 6da - 6x - 2da - 4da^2 + 4xda}{2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3}da} \\

(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} - \sqrt{3}x)(2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3}da) &= 3 + 6da - 6x - 2da - 4da^2 + 4xda \\

3 + 6da - 6x - 12xda &= 3 + 4da - 6x - 4da^2 + 4xda \\

2da &= -4da^2 + 16xda \\

16xda &= 2da + 4da^2 \\

x &= \frac{da + 2da^2}{8da}.

\end{align*}

We take the limit as ![]() to get

to get

![]() We substitute

We substitute ![]() into the equation for

into the equation for ![]() to find the y-coordinate of

to find the y-coordinate of ![]() :

:

![]() The problem asks for

The problem asks for

![]() so

so ![]() .

.

Solution 5 (small perturb)

![[asy] pair O=(0,0); pair X=(1,0); pair Y=(0,1); pair A=(0.5,0); pair B=(0,sin(pi/3)); pair A1=(0.6,0); pair B1=(0,0.8); pair A2=(0.575,0.04); pair B2=(0.03,0.816); dot(O); dot(X); dot(Y); dot(A); dot(B); dot(A1); dot(B1); dot(A2); dot(B2); draw(X--O--Y); draw(A--B); draw(A1--B1); draw(A--A2); draw(B1--B2); label("$B$", B, W); label("$A$", A, S); label("$B_1$", B1, SW); label("$A_1$", A1, S); label("$B_2$", B2, E); label("$A_2$", A2, NE); label("$O$", O, SW); pair C=(0.18,0.56); label("$C$", C, E); dot(C); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/5/b/8/5b8b2170c51ddfe08233b19df590742415215e94.png)

Let's move a little bit from ![]() to

to ![]() , then

, then ![]() must move to

must move to ![]() to keep

to keep ![]() .

. ![]() intersects with

intersects with ![]() at

at ![]() . Pick points

. Pick points ![]() and

and ![]() on

on ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that ![]() ,

, ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is very small,

is very small, ![]() ,

, ![]() , so

, so ![]() ,

, ![]() , by similarity,

, by similarity,  . So the coordinates of

. So the coordinates of ![]() is

is  .

.

so ![]() , the answer is

, the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 6(trig identities and questionable rigidity)

Let's try to find the general form of a line that is in ![]() based on what angle it makes with the x-axis,

based on what angle it makes with the x-axis, ![]() , and

, and ![]() so its slope is

so its slope is ![]() and due to us knowing its y-intercept we know that our line has form

and due to us knowing its y-intercept we know that our line has form ![]()

Now we can analyze the system of equations made by ![]() and

and ![]() , this gives us that

, this gives us that ![]()

We can proceed to simplify our expression further:

![]()

![]()

![\[= \dfrac{2\sin{\dfrac{\theta - 60^\circ}{2}}\cos{\dfrac{\theta + 60^\circ}{2}}}{\dfrac{2\sin{\dfrac{\theta - 60^\circ}{2}}\cos{\dfrac{\theta - 60^\circ}{2}}}{\cos{\theta}\cos{60^\circ}}}\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/1/d/b/1dbb478649ada70d8d69ed54c549424536588f0d.png)

![\[= \dfrac{\sin{\dfrac{\theta - 60^\circ}{2}}}{\sin{\dfrac{\theta - 60^\circ}{2}}} \cdot \dfrac{\cos{\theta}\cos{60^\circ}\cos{\dfrac{\theta + 60^\circ}{2}}}{\cos{\dfrac{\theta - 60^\circ}{2}}}.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/9/5/e/95ef1cb7bc18554776b76e4cfa61e3dfdd140899.png)

Seeing that there are only valid solutions when ![]() is acute(all that is allowed anyways) and when

is acute(all that is allowed anyways) and when ![]() since one of the expressions in our simplified solution will equal

since one of the expressions in our simplified solution will equal ![]() . Since there is only one intersection point for every

. Since there is only one intersection point for every ![]() and vice versa in the appropriate domain and range(we can easily prove this by contradiction), we know that the missing element of the range(the points) must correspond with the excluded value. The x-coordinate of which which can be evaluated by taking the limit of our expression as

and vice versa in the appropriate domain and range(we can easily prove this by contradiction), we know that the missing element of the range(the points) must correspond with the excluded value. The x-coordinate of which which can be evaluated by taking the limit of our expression as ![]() goes to

goes to ![]() which is

which is ![]() regardless of the direction we approach

regardless of the direction we approach ![]() from. The corresponding

from. The corresponding ![]() is

is ![]() and using the distance formula gives us

and using the distance formula gives us ![]() as our answer.

as our answer.

While this solution may seem long all of these steps come naturally.

~SailS

Solution 7

Denote ![]()

![]() Then

Then ![]()

Let ![]() be the point with property

be the point with property ![]()

![]()

So locus of points ![]() is the ellipse with semiaxes

is the ellipse with semiaxes ![]() and

and ![]()

Point ![]() is a unique point on

is a unique point on ![]() if the ellipse is tangent to the line

if the ellipse is tangent to the line ![]()

In this case in point ![]() we get

we get ![]()

The tangent of the line ![]() is

is ![]()

For point ![]() we get

we get ![]()

![]()

For the line ![]()

![\[D = \left( \frac{\cos \theta}{k+1}, \frac{k \sin \theta}{k+1} \right) = \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+ \tan^2 \theta} \cdot (k+1)}, \frac{k \tan \theta}{\sqrt{1+ \tan^2 \theta} \cdot (k+1)} \right) =\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/b/9/b/b9b16c586458cf18ae9e8547c48817693ff0a492.png)

so we get

so we get ![]() .

.

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

Solution 8 (intuitive elementary calculus solution)

First, we find the equation of the line ![]()

![]() Now, say we have some line in

Now, say we have some line in ![]() that spans from point

that spans from point ![]() at

at ![]() , and because this segment has unit length, ends at point

, and because this segment has unit length, ends at point ![]() located at

located at ![]() . Note that

. Note that ![]() has the equation

has the equation

![]() We notice that as

We notice that as ![]() varies,

varies, ![]() will intersect

will intersect ![]() at all points on

at all points on ![]() except point

except point ![]() . We make the key observation that

. We make the key observation that ![]() is what the intersection point of

is what the intersection point of ![]() and

and ![]() approaches as

approaches as ![]() approaches

approaches ![]() .

.

To find this point, let's find the intersection point of ![]() and

and ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() .

\begin{align*}

y &= -\sqrt{3} x + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

y &= -\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}x + a \\

-\sqrt{3} x + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} &= -\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}x + a \\

(\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}} - \sqrt{3}) \cdot x &= a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

x &= \dfrac{(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}}{a - \sqrt{3} \cdot \sqrt{1-a^2}} \\

\end{align*}

.

\begin{align*}

y &= -\sqrt{3} x + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

y &= -\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}x + a \\

-\sqrt{3} x + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} &= -\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}x + a \\

(\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}} - \sqrt{3}) \cdot x &= a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

x &= \dfrac{(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}}{a - \sqrt{3} \cdot \sqrt{1-a^2}} \\

\end{align*}

Note that we don't need to find the ![]() -coordinate because we know that this point is on line

-coordinate because we know that this point is on line ![]() , and once we find the

, and once we find the ![]() -coordinate, we can simply plug it into the equation of line

-coordinate, we can simply plug it into the equation of line ![]()

Now, we want to find ![\[ \lim_{a\to\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}} \dfrac{(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}}{a - \sqrt{3} \cdot \sqrt{1-a^2}} \]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/c/1/e/c1e506ab20c3bfda61543653be53a856644b772e.png) We apply L'Hopital's Rule as this limit is indeterminate.

Taking the derivative of the numerator using product rule:

\begin{align*}

\dfrac{d}{da} \left[(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}\right] &= \sqrt{1-a^2} \cdot \dfrac{d}{da} \left(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) + \dfrac{d}{da} \left(\sqrt{1-a^2}\right) \cdot (a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})

\end{align*}

Note that we can apply the chain rule to get

We apply L'Hopital's Rule as this limit is indeterminate.

Taking the derivative of the numerator using product rule:

\begin{align*}

\dfrac{d}{da} \left[(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}\right] &= \sqrt{1-a^2} \cdot \dfrac{d}{da} \left(a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) + \dfrac{d}{da} \left(\sqrt{1-a^2}\right) \cdot (a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2})

\end{align*}

Note that we can apply the chain rule to get ![]() \begin{align*}

&= \sqrt{1-a^2} + \dfrac{-a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}} * (a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}) \\

&= \dfrac{-2a^2 + \dfrac{a\sqrt{3}}{2} + 1}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}

\end{align*}

Taking the derivative of the denominator:

\begin{align*}

\dfrac{d}{da} \left[a-\sqrt{3}\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}\right] &= \dfrac{d}{da} (a) - \sqrt{3}\dfrac{d}{da}(\sqrt{1-a^2}) \\

&= 1 - \sqrt{3}\cdot\dfrac{-a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}} \\

&= \dfrac{\sqrt{1-a^2} + \sqrt{3}a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}

\end{align*}

So, our final expression is

\begin{align*}

&= \sqrt{1-a^2} + \dfrac{-a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}} * (a-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}) \\

&= \dfrac{-2a^2 + \dfrac{a\sqrt{3}}{2} + 1}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}

\end{align*}

Taking the derivative of the denominator:

\begin{align*}

\dfrac{d}{da} \left[a-\sqrt{3}\cdot\sqrt{1-a^2}\right] &= \dfrac{d}{da} (a) - \sqrt{3}\dfrac{d}{da}(\sqrt{1-a^2}) \\

&= 1 - \sqrt{3}\cdot\dfrac{-a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}} \\

&= \dfrac{\sqrt{1-a^2} + \sqrt{3}a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}

\end{align*}

So, our final expression is ![\[ \dfrac{\frac{-2a^2 + \frac{a\sqrt{3}}{2} + 1}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}}{\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2} + \sqrt{3}a}{\sqrt{1-a^2}}} \]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/b/0/b/b0b0a7b239d752cf372c1a1d645a5d4992aec0b0.png)

![]()

Now, all that remains is to substitute ![]() \begin{align*}

&= \dfrac{-\dfrac{3}{2} + \dfrac{3}{4} + 1}{\dfrac{1}{2} + \dfrac{3}{2}} \\

&= \dfrac{1}{8}

\end{align*}

Now, we can plug in

\begin{align*}

&= \dfrac{-\dfrac{3}{2} + \dfrac{3}{4} + 1}{\dfrac{1}{2} + \dfrac{3}{2}} \\

&= \dfrac{1}{8}

\end{align*}

Now, we can plug in ![]() into the equation of

into the equation of ![]() :

\begin{align*}

y &= -\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{8} + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

y &= \dfrac{3\sqrt{3}}{8}

\end{align*}

So point C is located at

:

\begin{align*}

y &= -\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{8} + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

y &= \dfrac{3\sqrt{3}}{8}

\end{align*}

So point C is located at ![]() The question asks for

The question asks for ![]() , so we simply apply the Pythagorean Theorem:

\begin{align*}

OC^2 &= (\dfrac{1}{8})^2 + (\dfrac{3\sqrt{3}}{2})^2 \\

OC^2 &= \dfrac{7}{16}\\

7 + 16 &= \boxed{23}

\end{align*}

, so we simply apply the Pythagorean Theorem:

\begin{align*}

OC^2 &= (\dfrac{1}{8})^2 + (\dfrac{3\sqrt{3}}{2})^2 \\

OC^2 &= \dfrac{7}{16}\\

7 + 16 &= \boxed{23}

\end{align*}

~143466534811009我输了游戏56二伯

Video Solution

https://youtu.be/914687Yv6SY?si=tc6XfoOIHu0gu6AL

(no calculus)

~MathProblemSolvingSkills.com

Video Solution

~Steven Chen (Professor Chen Education Palace, www.professorchenedu.com)

Query

![[asy] pair O=(0,0); pair X=(1,0); pair Y=(0,1); pair A=(0.5,0); pair B=(0,sin(pi/3)); dot(O); dot(X); dot(Y); dot(A); dot(B); draw(X--O--Y); draw(A--B); label("$B$", B, W); pair P=(0.5, sin(pi/3)); dot(P); draw(A--P--B); label("$A$", A, S); label("$O$", O, SW); pair C=(1/8,3*sqrt(3)/8); dot(C); label("$C$", C, SW); draw(C--P); label("$P$", P, NE); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/8/1/2/8127f1ad0f774d25ffc13e4b52ee26adb0ca7b54.png) Let

Let ![]() be a fixed point in the first quadrant. Let

be a fixed point in the first quadrant. Let ![]() be a point on the positive

be a point on the positive ![]() -axis and

-axis and ![]() be a point on the positive

be a point on the positive ![]() -axis such that

-axis such that ![]() passes through

passes through ![]() and the length of

and the length of ![]() is minimal. Let

is minimal. Let ![]() be the point such that

be the point such that ![]() is a rectangle. Prove that

is a rectangle. Prove that ![]() . (One can solve this through algebra/calculus bash, but I'm trying to find a solution that mainly uses geometry. If you know such a solution, write it here on this wiki page.) ~Furaken

. (One can solve this through algebra/calculus bash, but I'm trying to find a solution that mainly uses geometry. If you know such a solution, write it here on this wiki page.) ~Furaken

I think there is such a geometry way:

Let ![]() pass through

pass through ![]() while point

while point ![]() is on the outside of line segment

is on the outside of line segment ![]() and point

and point ![]() is in between

is in between ![]() and

and ![]() . We aim to show

. We aim to show ![]() is longer than

is longer than ![]() . Now since

. Now since ![]() is the altitude of triangle

is the altitude of triangle ![]() yet just a cevian on the base

yet just a cevian on the base ![]() of triangle

of triangle ![]() (thus making the height shorter than

(thus making the height shorter than ![]() ), it suffices to show the area of triangle

), it suffices to show the area of triangle ![]() is bigger than that of triangle

is bigger than that of triangle ![]() . To do this, we compare these two triangles (let

. To do this, we compare these two triangles (let ![]() intersect

intersect ![]() at point

at point ![]() ), and we just want to show

), and we just want to show ![]() . This is trivial by similarity ratios. ~gougutheorem

. This is trivial by similarity ratios. ~gougutheorem

Thanks! Now we know that it's possible to solve the AIME problem with only geometry. ~Furaken

Can someone better explain this solution please? How does ![]() show that

show that ![]() is bigger than

is bigger than ![]() ? ~inaccessibles

? ~inaccessibles

See also

| 2024 AIME II (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 11 |

Followed by Problem 13 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions. ![]()