Difference between revisions of "2012 AMC 12B Problems/Problem 19"

(Created page with "==Solution== File:2012_AMC-12B-19.jpg Observe the diagram above. Each dot represents one of the six vertices of the regular octahedron. Three dots have been placed exact...") |

Arcticturn (talk | contribs) (→Solution 1) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ==Solution== | + | ==Problem== |

| + | A unit cube has vertices <math>P_1,P_2,P_3,P_4,P_1',P_2',P_3',</math> and <math>P_4'</math>. Vertices <math>P_2</math>, <math>P_3</math>, and <math>P_4</math> are adjacent to <math>P_1</math>, and for <math>1\le i\le 4,</math> vertices <math>P_i</math> and <math>P_i'</math> are opposite to each other. A regular octahedron has one vertex in each of the segments <math>P_1P_2</math>, <math>P_1P_3</math>, <math>P_1P_4</math>, <math>P_1'P_2'</math>, <math>P_1'P_3'</math>, and <math>P_1'P_4'</math>. What is the octahedron's side length? | ||

| + | |||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | import three; | ||

| + | |||

| + | size(7.5cm); | ||

| + | triple eye = (-4, -8, 3); | ||

| + | currentprojection = perspective(eye); | ||

| + | |||

| + | triple[] P = {(1, -1, -1), (-1, -1, -1), (-1, 1, -1), (-1, -1, 1), (1, -1, -1)}; // P[0] = P[4] for convenience | ||

| + | triple[] Pp = {-P[0], -P[1], -P[2], -P[3], -P[4]}; | ||

| + | |||

| + | // draw octahedron | ||

| + | triple pt(int k){ return (3*P[k] + P[1])/4; } | ||

| + | triple ptp(int k){ return (3*Pp[k] + Pp[1])/4; } | ||

| + | draw(pt(2)--pt(3)--pt(4)--cycle, gray(0.6)); | ||

| + | draw(ptp(2)--pt(3)--ptp(4)--cycle, gray(0.6)); | ||

| + | draw(ptp(2)--pt(4), gray(0.6)); | ||

| + | draw(pt(2)--ptp(4), gray(0.6)); | ||

| + | draw(pt(4)--ptp(3)--pt(2), gray(0.6) + linetype("4 4")); | ||

| + | draw(ptp(4)--ptp(3)--ptp(2), gray(0.6) + linetype("4 4")); | ||

| + | |||

| + | // draw cube | ||

| + | for(int i = 0; i < 4; ++i){ | ||

| + | draw(P[1]--P[i]); draw(Pp[1]--Pp[i]); | ||

| + | for(int j = 0; j < 4; ++j){ | ||

| + | if(i == 1 || j == 1 || i == j) continue; | ||

| + | draw(P[i]--Pp[j]); draw(Pp[i]--P[j]); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | dot(P[i]); dot(Pp[i]); | ||

| + | dot(pt(i)); dot(ptp(i)); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | |||

| + | label("$P_1$", P[1], dir(P[1])); | ||

| + | label("$P_2$", P[2], dir(P[2])); | ||

| + | label("$P_3$", P[3], dir(-45)); | ||

| + | label("$P_4$", P[4], dir(P[4])); | ||

| + | label("$P'_1$", Pp[1], dir(Pp[1])); | ||

| + | label("$P'_2$", Pp[2], dir(Pp[2])); | ||

| + | label("$P'_3$", Pp[3], dir(-100)); | ||

| + | label("$P'_4$", Pp[4], dir(Pp[4])); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\textbf{(A)}\ \frac{3\sqrt{2}}{4}\qquad\textbf{(B)}\ \frac{7\sqrt{6}}{16}\qquad\textbf{(C)}\ \frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\qquad\textbf{(D)}\ \frac{2\sqrt{3}}{3}\qquad\textbf{(E)}\ \frac{\sqrt{6}}{2}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 1== | ||

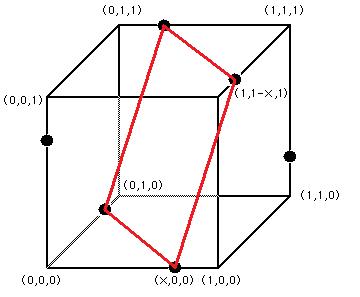

[[File:2012_AMC-12B-19.jpg]] | [[File:2012_AMC-12B-19.jpg]] | ||

| − | Observe the diagram above. Each dot represents one of the six vertices of the regular octahedron. Three dots have been placed exactly x units from the (0,0,0) corner of the unit cube. The other three dots have been placed exactly x units from the (1,1,1) corner of the unit cube. A red square has been drawn connecting four of the dots to provide perspective regarding the shape of the octahedron. Observe that the three dots that are near (0,0,0) are each x | + | Observe the diagram above. Each dot represents one of the six vertices of the regular octahedron. Three dots have been placed exactly x units from the <math>(0,0,0)</math> corner of the unit cube. The other three dots have been placed exactly x units from the <math>(1,1,1)</math> corner of the unit cube. A red square has been drawn connecting four of the dots to provide perspective regarding the shape of the octahedron. Observe that the three dots that are near <math>(0,0,0)</math> are each <math>(x)(\sqrt{2}</math>) from each other. The same is true for the three dots that are near <math>(1,1,1).</math> There is a unique <math>x</math> for which the rectangle drawn in red becomes a square. This will occur when the distance from <math>(x,0,0)</math> to <math>(1,1-x, 1)</math> is <math>(x)(\sqrt{2}</math>). |

| − | Using the distance formula we find the distance between the two points to be: sqrt | + | Using the distance formula we find the distance between the two points to be: <math>\sqrt{{(1-x)^2} + {(1-x)^2} + 1}</math> = <math>\sqrt{2x^2 - 4x +3}</math>. Equating this to <math>(x)(\sqrt{2}</math>) and squaring both sides, we have the equation: |

| − | + | <math>2{x^2} - 4x + 3</math> = <math>2{x^2}</math> | |

| − | -4x + 3 = 0 | + | <math>-4x + 3 = 0</math> |

| − | x = 3/ | + | <math>x</math> = <math>\frac{3} {4}</math>. |

| − | Since the length of each side is x | + | Since the length of each side is <math>(x)(\sqrt{2}</math>), we have a final result of <math>\frac{3 \sqrt{2}}{4}</math>. Thus, Answer choice <math>\boxed{\text{A}}</math> is correct. |

| Line 21: | Line 67: | ||

--[[User:Jm314|Jm314]] 14:55, 26 February 2012 (EST) | --[[User:Jm314|Jm314]] 14:55, 26 February 2012 (EST) | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Solution 2 == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Standard 3D geometry, no coordinates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Let the tip of the octahedron on side <math>P_1P_3</math> be <math>K_1</math> and the opposite vertex be <math>K_2</math>. Our key is to examine the trapezoid <math>P_1K_1K_2P_3</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Let the side length of the octahedron be <math>s</math>. Then <math>P_1K_1 = \frac{s}{\sqrt{2}}</math> and <math>P_3K_2 = 1 - \frac{2}{\sqrt{2}}</math>. Then, we have <math>P_1P_3 = \sqrt{2}</math>. Finally, we want to find <math>K_1K_2</math>, which is just double the height of half the octahedron. We can use Pythagorean Theorem to find that height as <math>\sqrt{2}s</math>. Now, we use the Pythagorean Theorem on the trapezoid. We get | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(\sqrt{2})^2 + (2\sqrt{2}-1)^2 = (s\sqrt{2})^2</cmath> <cmath>s = \frac{3\sqrt{2}}{4}.</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~superagh | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 3== | ||

| + | |||

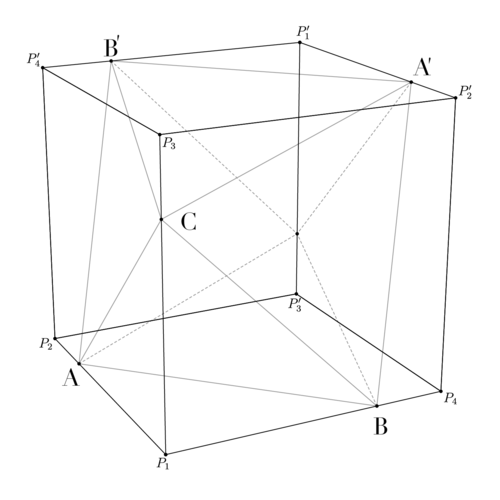

| + | [[File:2012AMC12BProblem19Solution3.png|center|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let the length of <math>P_1A = a</math>, <math>P_1B = b</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>AB = a^2 + b^2</math>, <math>AB' = (1-b)^2 + (1-a)^2 + 1</math>, <math>AB = AB'</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>a^2 + b^2 = (1-b)^2 + (1-a)^2 + 1</math>, <math>a^2 + b^2 = 1 - 2b + b^2 + 1 - 2a + a^2 + 1</math>, <math>a+ b = \frac32</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As <math>AC = BC</math>, <math>a^2 + P_1C^2 = b^2 + P_1C^2</math>, <math>a = b</math>, <math>a = \frac34</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>AB = \boxed{\textbf{(A) } \frac{3\sqrt{2}}{4}}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~[https://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php/User:Isabelchen isabelchen] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == See Also == | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{AMC12 box|year=2012|ab=B|num-b=18|num-a=20}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Introductory Geometry Problems]] | ||

| + | [[Category:3D Geometry Problems]] | ||

| + | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:59, 19 September 2023

Problem

A unit cube has vertices ![]() and

and ![]() . Vertices

. Vertices ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are adjacent to

are adjacent to ![]() , and for

, and for ![]() vertices

vertices ![]() and

and ![]() are opposite to each other. A regular octahedron has one vertex in each of the segments

are opposite to each other. A regular octahedron has one vertex in each of the segments ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . What is the octahedron's side length?

. What is the octahedron's side length?

![[asy] import three; size(7.5cm); triple eye = (-4, -8, 3); currentprojection = perspective(eye); triple[] P = {(1, -1, -1), (-1, -1, -1), (-1, 1, -1), (-1, -1, 1), (1, -1, -1)}; // P[0] = P[4] for convenience triple[] Pp = {-P[0], -P[1], -P[2], -P[3], -P[4]}; // draw octahedron triple pt(int k){ return (3*P[k] + P[1])/4; } triple ptp(int k){ return (3*Pp[k] + Pp[1])/4; } draw(pt(2)--pt(3)--pt(4)--cycle, gray(0.6)); draw(ptp(2)--pt(3)--ptp(4)--cycle, gray(0.6)); draw(ptp(2)--pt(4), gray(0.6)); draw(pt(2)--ptp(4), gray(0.6)); draw(pt(4)--ptp(3)--pt(2), gray(0.6) + linetype("4 4")); draw(ptp(4)--ptp(3)--ptp(2), gray(0.6) + linetype("4 4")); // draw cube for(int i = 0; i < 4; ++i){ draw(P[1]--P[i]); draw(Pp[1]--Pp[i]); for(int j = 0; j < 4; ++j){ if(i == 1 || j == 1 || i == j) continue; draw(P[i]--Pp[j]); draw(Pp[i]--P[j]); } dot(P[i]); dot(Pp[i]); dot(pt(i)); dot(ptp(i)); } label("$P_1$", P[1], dir(P[1])); label("$P_2$", P[2], dir(P[2])); label("$P_3$", P[3], dir(-45)); label("$P_4$", P[4], dir(P[4])); label("$P'_1$", Pp[1], dir(Pp[1])); label("$P'_2$", Pp[2], dir(Pp[2])); label("$P'_3$", Pp[3], dir(-100)); label("$P'_4$", Pp[4], dir(Pp[4])); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/5/9/d/59d2570727a6deab28e0d8d2be5154efc56b50ca.png)

![]()

Solution 1

Observe the diagram above. Each dot represents one of the six vertices of the regular octahedron. Three dots have been placed exactly x units from the ![]() corner of the unit cube. The other three dots have been placed exactly x units from the

corner of the unit cube. The other three dots have been placed exactly x units from the ![]() corner of the unit cube. A red square has been drawn connecting four of the dots to provide perspective regarding the shape of the octahedron. Observe that the three dots that are near

corner of the unit cube. A red square has been drawn connecting four of the dots to provide perspective regarding the shape of the octahedron. Observe that the three dots that are near ![]() are each

are each ![]() ) from each other. The same is true for the three dots that are near

) from each other. The same is true for the three dots that are near ![]() There is a unique

There is a unique ![]() for which the rectangle drawn in red becomes a square. This will occur when the distance from

for which the rectangle drawn in red becomes a square. This will occur when the distance from ![]() to

to ![]() is

is ![]() ).

).

Using the distance formula we find the distance between the two points to be: ![]() =

= ![]() . Equating this to

. Equating this to ![]() ) and squaring both sides, we have the equation:

) and squaring both sides, we have the equation:

![]() =

= ![]()

![]()

![]() =

= ![]() .

.

Since the length of each side is ![]() ), we have a final result of

), we have a final result of ![]() . Thus, Answer choice

. Thus, Answer choice ![]() is correct.

is correct.

(If someone can draw a better diagram with the points labeled P1,P2, etc., I would appreciate it).

--Jm314 14:55, 26 February 2012 (EST)

Solution 2

Standard 3D geometry, no coordinates.

Let the tip of the octahedron on side ![]() be

be ![]() and the opposite vertex be

and the opposite vertex be ![]() . Our key is to examine the trapezoid

. Our key is to examine the trapezoid ![]() .

.

Let the side length of the octahedron be ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() and

and ![]() . Then, we have

. Then, we have ![]() . Finally, we want to find

. Finally, we want to find ![]() , which is just double the height of half the octahedron. We can use Pythagorean Theorem to find that height as

, which is just double the height of half the octahedron. We can use Pythagorean Theorem to find that height as ![]() . Now, we use the Pythagorean Theorem on the trapezoid. We get

. Now, we use the Pythagorean Theorem on the trapezoid. We get

![]()

![]()

~superagh

Solution 3

Let the length of ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]()

As ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]()

See Also

| 2012 AMC 12B (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | |

| Preceded by Problem 18 |

Followed by Problem 20 |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 | |

| All AMC 12 Problems and Solutions | |

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.