Difference between revisions of "Pythagorean Theorem"

Michael5210 (talk | contribs) m (→Proofs) |

m (Fixed LaTeX) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | The '''Pythagorean Theorem''' states that for a [[right triangle]] with | + | The '''Pythagorean Theorem''' states that for a [[right triangle]] with [[leg]]s of length <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> and [[hypotenuse]] of length <math>c</math> we have the relationship <math>a^2+b^2=c^2</math>. This theorem has been known since antiquity and is a classic to prove; hundreds of proofs have been published and many can be demonstrated entirely visually. The Pythagorean Theorem is one of the most frequently used theorems in [[geometry]], and is one of the many tools in a good geometer's arsenal. A very large number of geometry problems can be solved by building right triangles and applying the Pythagorean Theorem. |

| − | This is generalized by the [[Geometric inequality#Pythagorean_Inequality | Pythagorean Inequality]] and the [[Law of Cosines]]. | + | This is generalized by the [[Geometric inequality#Pythagorean_Inequality|Pythagorean Inequality]] and the [[Law of Cosines]]. |

== Proofs == | == Proofs == | ||

| − | In these proofs, we will let <math>ABC </math> be any right triangle with a right angle at <math>\angle ACB</math>. | + | In these proofs, we will let <math>ABC</math> be any right triangle with a right angle at <math>\angle ACB</math>, and we use <math>[ABC]</math> to denote the area of triangle <math>ABC</math>. |

=== Proof 1 === | === Proof 1 === | ||

| − | + | Let <math>D</math> be the foot of the [[altitude]] from <math>C</math>. <math>ABC</math>, <math>ACD</math>, <math>BCD</math> are similar triangles, so <math>\frac{AC}{AD}=\frac{AB}{AC} \implies AC^2=(AD)(AB)</math> and <math>\frac{BC}{BD}=\frac{AB}{BC} \implies BC^2=(BD)(AB)</math>. Adding these equations gives us <math>AC^2+BC^2=(AD)(AB)+(BD)(AB) \implies AC^2+BC^2=(AB)(AD+BD) \implies AC^2+BC^2=AB^2</math> | |

| − | Let <math>H </math> be the | + | === Proof 2 === |

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>H</math> be the foot of the [[altitude]] from <math>C</math>. | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 34: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | Since <math>ABC, CBH, ACH</math> are similar right triangles, and the areas of similar triangles are proportional to the squares of corresponding side lengths, | + | Since <math>ABC</math>, <math>CBH</math>, <math>ACH</math> are similar right triangles, and the areas of similar triangles are proportional to the squares of corresponding side lengths, |

| − | < | + | <cmath>\frac{[ABC]}{AB^2} = \frac{[CBH]}{CB^2} = \frac{[ACH]}{AC^2}.</cmath> |

| − | + | But since triangle <math>ABC</math> is composed of triangles <math>CBH</math> and <math>ACH</math>, <math>[ABC] = [CBH]+[ACH]</math>, so <math>AB^2 = CB^2 + AC^2</math>. {{Halmos}} | |

| − | </ | ||

| − | But since triangle <math>ABC </math> is composed of triangles <math>CBH </math> and <math>ACH </math>, <math>[ABC] = [CBH] + [ACH] </math>, so <math>AB^2 = CB^2 + AC^2 </math>. {{Halmos}} | ||

| − | === Proof | + | === Proof 3 === |

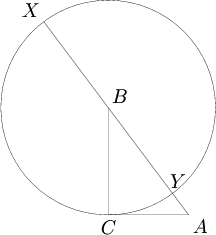

| − | Consider a circle <math>\omega </math> with center <math>B </math> and radius <math>BC </math>. Since <math>BC </math> and <math>AC </math> are perpendicular, <math>AC </math> is tangent to <math>\omega </math>. Let the line <math>AB </math> meet <math>\omega </math> at <math>Y </math> and <math>X </math>, as shown in the diagram: | + | Consider a circle <math>\omega</math> with center <math>B</math> and radius <math>BC</math>. Since <math>BC</math> and <math>AC</math> are perpendicular, <math>AC</math> is tangent to <math>\omega</math>. Let the line <math>AB</math> meet <math>\omega</math> at <math>Y</math> and <math>X</math>, as shown in the diagram: |

<center>[[Image:Pyth2.png]]</center> | <center>[[Image:Pyth2.png]]</center> | ||

| − | Evidently, <math>AY = AB - BC </math> and <math>AX = AB + BC </math>. By considering the [[Power of a Point | + | Evidently, <math>AY = AB-BC</math> and <math>AX = AB+BC</math>. By considering the [[Power of a Point]] <math>A</math> with respect to <math>\omega</math>, we see |

| − | + | <cmath>AC^2 = AY \cdot AX = (AB-BC)(AB+BC) = AB^2 - BC^2.</cmath> {{Halmos}} | |

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | === Proof | + | === Proof 4 === |

<math>ABCD</math> and <math>EFGH</math> are squares. | <math>ABCD</math> and <math>EFGH</math> are squares. | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<asy> | <asy> | ||

| − | pair A, B,C,D; | + | pair A,B,C,D; |

A = (-10,10); | A = (-10,10); | ||

B = (10,10); | B = (10,10); | ||

| Line 93: | Line 90: | ||

</asy> | </asy> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | <math>(a+b)^2=c^2+4\left(\frac{1}{2}ab\right)\implies a^2+2ab+b^2=c^2+2ab\implies a^2 + b^2=c^2</math>. {{Halmos}} | + | <math>(a+b)^2=c^2+4\left(\frac{1}{2}ab\right)\implies a^2+2ab+b^2=c^2+2ab\implies a^2+b^2=c^2</math>. {{Halmos}} |

| + | |||

| + | == Pythagorean Triples == | ||

| − | + | {{main|Pythagorean triple}} | |

| − | A [[Pythagorean | + | A [[Pythagorean triple]] is a [[triple]] of [[positive integer]]s such that <math>a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}</math>. All such triples contain numbers which are side lengths of the sides of a right triangle. Among these, the [[Primitive Pythagorean triple]]s, are those in which the three numbers are [[coprime]]. A few of them are: |

<cmath>3-4-5</cmath> | <cmath>3-4-5</cmath> | ||

| Line 107: | Line 106: | ||

<cmath>11-60-61</cmath> | <cmath>11-60-61</cmath> | ||

| + | Note that (3,4,5) is the only Pythagorean triple that consists of consecutive integers. | ||

| − | + | Any triple created by multiplying all three numbers in a Pythagorean triple by a positive integer is Pythagorean. In other words, if (a,b,c) is a Pythagorean triple it follows that (ka,kb,kc) will also form a Pythagorean triple for any positive integer constant k. | |

For example, | For example, | ||

<cmath>6-8-10 = (3-4-5)*2</cmath> | <cmath>6-8-10 = (3-4-5)*2</cmath> | ||

<cmath>21-72-75 = (7-24-25)*3</cmath> | <cmath>21-72-75 = (7-24-25)*3</cmath> | ||

<cmath>10-24-26 = (5-12-13)*2</cmath> | <cmath>10-24-26 = (5-12-13)*2</cmath> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Problems == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Introductory === | === Introductory === | ||

* [[2006_AIME_I_Problems/Problem_1 | 2006 AIME I Problem 1]] | * [[2006_AIME_I_Problems/Problem_1 | 2006 AIME I Problem 1]] | ||

* [[2007 AMC 12A Problems/Problem 10 | 2007 AMC 12A Problem 10]] | * [[2007 AMC 12A Problems/Problem 10 | 2007 AMC 12A Problem 10]] | ||

| − | === | + | === Problem 1 === |

Right triangle <math>ABC</math> has legs of length <math>333</math> and <math>444</math>. Find the hypotenuse of <math>ABC</math>. | Right triangle <math>ABC</math> has legs of length <math>333</math> and <math>444</math>. Find the hypotenuse of <math>ABC</math>. | ||

==== Solution 1 (Bash) ==== | ==== Solution 1 (Bash) ==== | ||

| − | <math>\sqrt{333^2 + 444^2} = 555</math>. | + | <math>\sqrt{333^2+444^2} = \boxed{555}</math>. |

==== Solution 2 (Using 3-4-5) ==== | ==== Solution 2 (Using 3-4-5) ==== | ||

| − | + | <math>333-444-555</math> is the resulting Pythagorean triple when <math>3-4-5</math> is multiplied by <math>11</math>, so the answer is <math>\boxed{555}</math>. | |

| − | === | + | === Problem 2 === |

Right triangle <math>ABC</math> has side lengths of <math>3</math> and <math>4</math>. Find the sum of all the possible hypotenuses. | Right triangle <math>ABC</math> has side lengths of <math>3</math> and <math>4</math>. Find the sum of all the possible hypotenuses. | ||

==== Solution (Casework) ==== | ==== Solution (Casework) ==== | ||

| Line 142: | Line 138: | ||

3 is a leg and 4 is the hypotenuse. | 3 is a leg and 4 is the hypotenuse. | ||

| − | There are no more cases as the hypotenuse has to be greater than the leg | + | There are no more cases as the hypotenuse has to be greater than the leg, so the sum is <math>4+5=\boxed{9}</math>. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| Line 150: | Line 144: | ||

[[Category:Geometry]] | [[Category:Geometry]] | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Theorems]] | [[Category:Theorems]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:44, 17 January 2025

The Pythagorean Theorem states that for a right triangle with legs of length ![]() and

and ![]() and hypotenuse of length

and hypotenuse of length ![]() we have the relationship

we have the relationship ![]() . This theorem has been known since antiquity and is a classic to prove; hundreds of proofs have been published and many can be demonstrated entirely visually. The Pythagorean Theorem is one of the most frequently used theorems in geometry, and is one of the many tools in a good geometer's arsenal. A very large number of geometry problems can be solved by building right triangles and applying the Pythagorean Theorem.

. This theorem has been known since antiquity and is a classic to prove; hundreds of proofs have been published and many can be demonstrated entirely visually. The Pythagorean Theorem is one of the most frequently used theorems in geometry, and is one of the many tools in a good geometer's arsenal. A very large number of geometry problems can be solved by building right triangles and applying the Pythagorean Theorem.

This is generalized by the Pythagorean Inequality and the Law of Cosines.

Contents

Proofs

In these proofs, we will let ![]() be any right triangle with a right angle at

be any right triangle with a right angle at ![]() , and we use

, and we use ![]() to denote the area of triangle

to denote the area of triangle ![]() .

.

Proof 1

Let ![]() be the foot of the altitude from

be the foot of the altitude from ![]() .

. ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are similar triangles, so

are similar triangles, so ![]() and

and ![]() . Adding these equations gives us

. Adding these equations gives us ![]()

Proof 2

Let ![]() be the foot of the altitude from

be the foot of the altitude from ![]() .

.

![[asy] pair A, B, C, H; A = (0, 0); B = (4, 3); C = (4, 0); H = foot(C, A, B); draw(A--B--C--cycle); draw(C--H); draw(rightanglemark(A, C, B)); draw(rightanglemark(C, H, B)); label("$A$", A, SSW); label("$B$", B, ENE); label("$C$", C, SE); label("$H$", H, NNW); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/a/1/9/a19bed9f5ac971139756a395da4e29366d45fc52.png)

Since ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are similar right triangles, and the areas of similar triangles are proportional to the squares of corresponding side lengths,

are similar right triangles, and the areas of similar triangles are proportional to the squares of corresponding side lengths,

![]() But since triangle

But since triangle ![]() is composed of triangles

is composed of triangles ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() , so

, so ![]() . ∎

. ∎

Proof 3

Consider a circle ![]() with center

with center ![]() and radius

and radius ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() and

and ![]() are perpendicular,

are perpendicular, ![]() is tangent to

is tangent to ![]() . Let the line

. Let the line ![]() meet

meet ![]() at

at ![]() and

and ![]() , as shown in the diagram:

, as shown in the diagram:

Evidently, ![]() and

and ![]() . By considering the Power of a Point

. By considering the Power of a Point ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() , we see

, we see

![]() ∎

∎

Proof 4

![]() and

and ![]() are squares.

are squares.

![[asy] pair A,B,C,D; A = (-10,10); B = (10,10); C = (10,-10); D = (-10,-10); pair E,F,G,H; E = (7,10); F = (10, -7); G = (-7, -10); H = (-10, 7); draw(A--B--C--D--cycle); label("$A$", A, NNW); label("$B$", B, ENE); label("$C$", C, ESE); label("$D$", D, SSW); draw(E--F--G--H--cycle); label("$E$", E, N); label("$F$", F,SE); label("$G$", G, S); label("$H$", H, W); label("a", A--B,N); label("a", B--F,SE); label("a", C--G,S); label("a", H--D,W); label("b", E--B,N); label("b", F--C,SE); label("b", G--D,S); label("b", A--H,W); label("c", E--H,NW); label("c", E--F); label("c", F--G,SE); label("c", G--H,SW); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/4/1/a/41a647e5a19503aef099a12685b97760238aaa77.png)

![]() . ∎

. ∎

Pythagorean Triples

- Main article: Pythagorean triple

A Pythagorean triple is a triple of positive integers such that ![]() . All such triples contain numbers which are side lengths of the sides of a right triangle. Among these, the Primitive Pythagorean triples, are those in which the three numbers are coprime. A few of them are:

. All such triples contain numbers which are side lengths of the sides of a right triangle. Among these, the Primitive Pythagorean triples, are those in which the three numbers are coprime. A few of them are:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Note that (3,4,5) is the only Pythagorean triple that consists of consecutive integers.

Any triple created by multiplying all three numbers in a Pythagorean triple by a positive integer is Pythagorean. In other words, if (a,b,c) is a Pythagorean triple it follows that (ka,kb,kc) will also form a Pythagorean triple for any positive integer constant k.

For example,

![]()

![]()

![]()

Problems

Introductory

Problem 1

Right triangle ![]() has legs of length

has legs of length ![]() and

and ![]() . Find the hypotenuse of

. Find the hypotenuse of ![]() .

.

Solution 1 (Bash)

![]() .

.

Solution 2 (Using 3-4-5)

![]() is the resulting Pythagorean triple when

is the resulting Pythagorean triple when ![]() is multiplied by

is multiplied by ![]() , so the answer is

, so the answer is ![]() .

.

Problem 2

Right triangle ![]() has side lengths of

has side lengths of ![]() and

and ![]() . Find the sum of all the possible hypotenuses.

. Find the sum of all the possible hypotenuses.

Solution (Casework)

Case 1:

3 and 4 are the legs. Then 5 is the hypotenuse.

Case 2:

3 is a leg and 4 is the hypotenuse.

There are no more cases as the hypotenuse has to be greater than the leg, so the sum is ![]() .

.