Difference between revisions of "2007 AIME I Problems/Problem 10"

(→Problem) |

m |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | __TOC__ | ||

| + | |||

== Problem == | == Problem == | ||

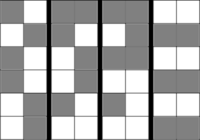

In a 6 x 4 grid (6 rows, 4 columns), 12 of the 24 squares are to be shaded so that there are two shaded squares in each row and three shaded squares in each column. Let <math>N</math> be the number of shadings with this property. Find the remainder when <math>N</math> is divided by 1000. | In a 6 x 4 grid (6 rows, 4 columns), 12 of the 24 squares are to be shaded so that there are two shaded squares in each row and three shaded squares in each column. Let <math>N</math> be the number of shadings with this property. Find the remainder when <math>N</math> is divided by 1000. | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:AIME I 2007-10.png]] | [[Image:AIME I 2007-10.png]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:12, 28 November 2023

Contents

Problem

In a 6 x 4 grid (6 rows, 4 columns), 12 of the 24 squares are to be shaded so that there are two shaded squares in each row and three shaded squares in each column. Let ![]() be the number of shadings with this property. Find the remainder when

be the number of shadings with this property. Find the remainder when ![]() is divided by 1000.

is divided by 1000.

Solution

Solution 1

Consider the first column. There are  ways that the rows could be chosen, but without loss of generality let them be the first three rows. (Change the order of the rows to make this true.) We will multiply whatever answer we get by 20 to get our final answer.

ways that the rows could be chosen, but without loss of generality let them be the first three rows. (Change the order of the rows to make this true.) We will multiply whatever answer we get by 20 to get our final answer.

Now consider the 3x3 that is next to the 3 boxes we have filled in. We must put one ball in each row (since there must be 2 balls in each row and we've already put one in each). We split into three cases:

- All three balls are in the same column. In this case, there are 3 choices for which column that is. From here, the bottom half of the board is fixed.

- Two balls are in one column, and one is in the other. In this case, there are 3 ways to choose which column gets 2 balls and 2 ways to choose which one gets the other ball. Then, there are 3 ways to choose which row the lone ball is in. Now, what happens in the bottom half of the board? Well, the 3 boxes in the column with no balls in the top half must all be filled in, so there are no choices here. In the column with two balls already, we can choose any of the 3 boxes for the third ball. This forces the location for the last two balls. So we have

.

.

- All three balls are in different columns. Then there are 3 ways to choose which row the ball in column 2 goes and 2 ways to choose where the ball in column 3 goes. (The location of the ball in column 4 is forced.) Again, we think about what happens in the bottom half of the board. There are 2 balls in each row and column now, so in the 3x3 where we still have choices, each row and column has one square that is not filled in. But there are 6 ways to do this. So in all there are 36 ways.

So there are ![]() different shadings, and the solution is

different shadings, and the solution is ![]() .

.

Solution 2

We start by showing that every group of ![]() rows can be grouped into

rows can be grouped into ![]() complementary pairs.

We proceed with proof by contradiction. Without loss of generality, assume that the first row has columns

complementary pairs.

We proceed with proof by contradiction. Without loss of generality, assume that the first row has columns ![]() and

and ![]() shaded. Note how if there is no complement to this, then all the other five rows must have at least one square in the first two columns shaded. That means that in total, the first two rows have

shaded. Note how if there is no complement to this, then all the other five rows must have at least one square in the first two columns shaded. That means that in total, the first two rows have ![]() squares shaded in- that is false since it should only be

squares shaded in- that is false since it should only be ![]() .

Thus, there exists another row that is complementary to the first. We remove those two and use a similar argument again to show that every group of

.

Thus, there exists another row that is complementary to the first. We remove those two and use a similar argument again to show that every group of ![]() rows can be grouped into

rows can be grouped into ![]() complementary pairs.

complementary pairs.

Now we proceed with three cases.

- There are

pairs of complementary pairs. The first case is that the three pairs are all different, meaning that every single possible pair of shaded squares is used once. This gives us

pairs of complementary pairs. The first case is that the three pairs are all different, meaning that every single possible pair of shaded squares is used once. This gives us

- Our second case is that two of the pairs are the same, and the third is different. We have

to choose the pair that shows up twice and

to choose the pair that shows up twice and  for the other, giving us

for the other, giving us

- Our final case is that all three pairs are the same. This is just

Our answer is thus ![]() leaving us with a final answer of

leaving us with a final answer of ![]()

Solution 3

We draw a bijection between walking from ![]() to

to ![]() as follows: if in the

as follows: if in the ![]() th row, the

th row, the ![]() th and

th and ![]() th columns are shaded, then the

th columns are shaded, then the ![]() st step is in the direction corresponding to

st step is in the direction corresponding to ![]() , and the

, and the ![]() th step is in the direction corresponding to

th step is in the direction corresponding to ![]() (

(![]() ) here. We can now use the Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion based on the stipulation that

) here. We can now use the Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion based on the stipulation that ![]() to solve the problem:

to solve the problem:

So that the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 4

There are ![]() to choose the arrangement of the shaded squares in each column. Examine the positioning of the shaded squares in the first two columns:

to choose the arrangement of the shaded squares in each column. Examine the positioning of the shaded squares in the first two columns:

- If column 1 and column 2 do not share any two filled squares on the same row, then there are

combinations for column 1, and then column 2 is fixed. Now, any row cannot have more than 2 shaded squares, so after we pick three more squares in the third column, the fourth column is also fixed. This gives

combinations for column 1, and then column 2 is fixed. Now, any row cannot have more than 2 shaded squares, so after we pick three more squares in the third column, the fourth column is also fixed. This gives  arrangements.

arrangements. - If column 1 and column 2 share 1 filled square on the same row (6 places), then they each share 1 filled square on a row (

places), share another empty square on a row, and have 2 squares each on different rows. This gives

places), share another empty square on a row, and have 2 squares each on different rows. This gives  . Now, the third and fourths columns must also share a fixed shared shaded square in the row in which the first two columns both had spaces, and another fixed empty square. The remaining shaded squares can only go in 4 places, so we get

. Now, the third and fourths columns must also share a fixed shared shaded square in the row in which the first two columns both had spaces, and another fixed empty square. The remaining shaded squares can only go in 4 places, so we get  . We get

. We get  .

. - If column 1 and column 2 share 2 filled squares on the same row (

places), they must also share 2 empty squares on the same row (

places), they must also share 2 empty squares on the same row ( ). The last two squares can be arranged in

). The last two squares can be arranged in  positions; this totals to

positions; this totals to  . Now, the third and fourth columns have a fixed 2 filled squares in common rows and 2 empty squares in common rows. The remaining 2 squares have

. Now, the third and fourth columns have a fixed 2 filled squares in common rows and 2 empty squares in common rows. The remaining 2 squares have  places, giving

places, giving  .

. - If column 1 and column 2 share 3 filled squares on the same row (

places), then the squares on columns 3 and 4 are fixed.

places), then the squares on columns 3 and 4 are fixed.

Thus, there are ![]() number of shadings, so the answer is

number of shadings, so the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 5

Consider all possible shadings for a single row. There are  ways to do so, and denote these as

ways to do so, and denote these as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() where

where ![]() indicates that columns

indicates that columns ![]() and

and ![]() are shaded. From our condition on the columns, we have

are shaded. From our condition on the columns, we have ![]() Summing the first two and the last two equations, we have

Summing the first two and the last two equations, we have ![]() , from which we have

, from which we have ![]() . Likewise,

. Likewise, ![]() and

and ![]() since these pairs shade in complimentary columns. So the six rows are paired up into a row and its compliment. In all, we can have 3 a's and 3 b's and similar setups for

since these pairs shade in complimentary columns. So the six rows are paired up into a row and its compliment. In all, we can have 3 a's and 3 b's and similar setups for ![]() /

/![]() and

and ![]() /

/![]() , 2 a's, 2 b's, 1 c and 1 d and similar setups for all six arrangements, or one of each. This first case gives

, 2 a's, 2 b's, 1 c and 1 d and similar setups for all six arrangements, or one of each. This first case gives  solutions; the second gives

solutions; the second gives  solutions, and the final case gives

solutions, and the final case gives ![]() solutions. In all, we have 1860 solutions, for an answer of

solutions. In all, we have 1860 solutions, for an answer of ![]() .

.

Solution 6

Each shading can be brought, via row swapping operations, to a state with a ![]() shaded

shaded ![]() in the lower left hand corner. The number of such arrangements multiplied by

in the lower left hand corner. The number of such arrangements multiplied by  will be the total. Consider rows 2 and 3 up from the bottom: they each have one of their allotted two squares shaded. Depending how the remaining three shades are distributed, the column totals of columns 2,3, and 4 from the left can be of the form

will be the total. Consider rows 2 and 3 up from the bottom: they each have one of their allotted two squares shaded. Depending how the remaining three shades are distributed, the column totals of columns 2,3, and 4 from the left can be of the form ![]() .

Form 1: The entire lower left

.

Form 1: The entire lower left ![]() rectangle is shaded, forcing the opposite

rectangle is shaded, forcing the opposite ![]() rectangle to also be shaded; thus 1 arrangement

Form 2: There is a column with nothing shaded in the bottom right

rectangle to also be shaded; thus 1 arrangement

Form 2: There is a column with nothing shaded in the bottom right ![]() , so it must be completely shaded in the upper right

, so it must be completely shaded in the upper right ![]() . Now consider the upper right half column that will have

. Now consider the upper right half column that will have ![]() shade. There are

shade. There are ![]() ways of choosing this shade, and all else is determined from here; thus 3 arrangements

Form 3: The upper right

ways of choosing this shade, and all else is determined from here; thus 3 arrangements

Form 3: The upper right ![]() will have exactly

will have exactly ![]() shades per column and row. This is equivalent to the number of terms in a

shades per column and row. This is equivalent to the number of terms in a ![]() determinant, or

determinant, or ![]() arrangements

arrangements

Of the ![]() ways of choosing to complete the bottom half of the

ways of choosing to complete the bottom half of the ![]() , form 1 is achieved in exactly 1 way; form 2 is achieved in

, form 1 is achieved in exactly 1 way; form 2 is achieved in ![]() ways; and form

ways; and form ![]() in the remaining

in the remaining ![]() ways.

Thus, the weighted total is

ways.

Thus, the weighted total is ![]() .

Complete:

.

Complete: ![]()

Solution 7

Note that if we find a valid shading of the first 3 columns, the shading of the last column is determined. We also note that within the first 3 columns, there will be 3 rows with 1 shaded square and 3 rows with 2 shaded squares.

There are ![]() ways to choose which rows have 1 shaded square (which we'll call a "1-row") within the first 3 columns and which rows have 2 (we'll call these "2-rows") within the first 3 columns. Next, we do some casework:

ways to choose which rows have 1 shaded square (which we'll call a "1-row") within the first 3 columns and which rows have 2 (we'll call these "2-rows") within the first 3 columns. Next, we do some casework:

- If all of the shaded squares in the first column are in a 1-row, then the squares in the second and third columns must be in the 2-rows. Thus there is only

valid shading in this case.

valid shading in this case.

- If 2 of the shaded squares in the first column are in a 1-row, and the third shaded square is in a 2-row, then the other shaded square in that 2-row can either be in column 3 or column 4. Once we determine that, the other shaded squares are uniquely determined. Thus, there are

valid shadings in this case.

valid shadings in this case.

- If 1 shaded square in the first column is in a 1-row, and the other 2 are in 2-rows, then the 2-row without a shaded square in the first column must have shaded squares in both column 2 and column 3. This leaves 4 possible squares in the second column to be shaded (since there can't be another shaded square in the occupied 1-row). Thus, there are

valid shadings in this case. (We only need to choose 2, since 1 of the shaded squares in the third column must go to the unoccupied 2-row).

valid shadings in this case. (We only need to choose 2, since 1 of the shaded squares in the third column must go to the unoccupied 2-row).

- If all of the shaded squares in the first column are in the 3 2-rows, then if we choose any 3 squares in the second column to be shaded, then the third column is uniquely determined to create a valid shading. Thus, there are

valid shadings in this case.

valid shadings in this case.

In total, we have  . Thus our answer is

. Thus our answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 8

We can use generating functions. Suppose that the variables ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() represent shading a square that appears in the first, second, third, or fourth columns, respectively. Then if two squares in the row are shaded, then the row is represented by the generating function

represent shading a square that appears in the first, second, third, or fourth columns, respectively. Then if two squares in the row are shaded, then the row is represented by the generating function ![]() , which we can write as

, which we can write as ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() represents all of the possible ways to color six rows such that each row has two shaded squares. We only want the possibilities when each column has three shaded squares, or rather, the coefficient of

represents all of the possible ways to color six rows such that each row has two shaded squares. We only want the possibilities when each column has three shaded squares, or rather, the coefficient of ![]() in

in ![]() .

.

By the Binomial Theorem,

![\[P(a,b,c,d)^6=\sum_{k=0}^6 \binom{6}{k} (ab+cd)^k(a+b)^{6-k}(c+d)^{6-k}.\tag{1}\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/e/c/7/ec784e66fce4df3cdc72a9bde582d7f5da104792.png) If we expand

If we expand ![]() , then the powers of

, then the powers of ![]() and

and ![]() are always equal. Therefore, to obtain terms of the form

are always equal. Therefore, to obtain terms of the form ![]() , the powers of

, the powers of ![]() and

and ![]() in

in ![]() must be equal. In particular, only the central term in the binomial expansion will contribute, and this implies that

must be equal. In particular, only the central term in the binomial expansion will contribute, and this implies that ![]() must be even. We can use the same logic for

must be even. We can use the same logic for ![]() and

and ![]() . Therefore, the coefficient of

. Therefore, the coefficient of ![]() in the following expression is the same as the coefficient of

in the following expression is the same as the coefficient of ![]() in (1).

in (1).

![\[\sum_{k=0}^3 \binom{6}{2k} (ab+cd)^{2k}(ab)^{3-k}(cd)^{3-k}\binom{6-2k}{3-k}^2.\tag{2}\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/1/e/2/1e2d487f8507a7264f744d3ae3917ee8af05dcac.png) Now we notice that the only way to obtain terms of the form

Now we notice that the only way to obtain terms of the form ![]() is if we take the central term in the binomial expansion of

is if we take the central term in the binomial expansion of ![]() . Therefore, the terms that contribute to the coefficient of

. Therefore, the terms that contribute to the coefficient of ![]() in (2) are

in (2) are

![\[\sum_{k=0}^3 \binom{6}{2k}\binom{2k}{k}\binom{6-2k}{3-k}^2(abcd)^3.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/4/5/0/450b87491dfb249da71fe0b355eb884b7ee2caf3.png) This sum is

This sum is ![]() so the answer is

so the answer is ![]() .

.

See also

| 2007 AIME I (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 9 |

Followed by Problem 11 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.

arrangements.

arrangements. . Now, the third and fourths columns must also share a fixed shared shaded square in the row in which the first two columns both had spaces, and another fixed empty square. The remaining shaded squares can only go in 4 places, so we get

. Now, the third and fourths columns must also share a fixed shared shaded square in the row in which the first two columns both had spaces, and another fixed empty square. The remaining shaded squares can only go in 4 places, so we get  . We get

. We get  places), they must also share 2 empty squares on the same row (

places), they must also share 2 empty squares on the same row ( positions; this totals to

positions; this totals to  valid shading in this case.

valid shading in this case. valid shadings in this case.

valid shadings in this case. valid shadings in this case. (We only need to choose 2, since 1 of the shaded squares in the third column must go to the unoccupied 2-row).

valid shadings in this case. (We only need to choose 2, since 1 of the shaded squares in the third column must go to the unoccupied 2-row). valid shadings in this case.

valid shadings in this case.