Difference between revisions of "2021 Fall AMC 12B Problems/Problem 20"

Ehuang0531 (talk | contribs) (→Solution 1 (Direct Counting)) |

m (minor grammar edits) |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{duplicate|[[2021 Fall AMC 12B Problems#Problem 20|2021 Fall AMC 12B #20]] and [[2021 Fall AMC 10B Problems#Problem 24|2021 Fall AMC | + | {{duplicate|[[2021 Fall AMC 12B Problems#Problem 20|2021 Fall AMC 12B #20]] and [[2021 Fall AMC 10B Problems#Problem 24|2021 Fall AMC 10B #24]]}} |

==Problem== | ==Problem== | ||

| − | A cube is constructed from <math>4</math> white unit cubes and <math>4</math> | + | A cube is constructed from <math>4</math> white unit cubes and <math>4</math> blue unit cubes. How many different ways are there to construct the <math>2 \times 2 \times 2</math> cube using these smaller cubes? (Two constructions are considered the same if one can be rotated to match the other.) |

<math>\textbf{(A)}\ 7 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 8 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 9 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ | <math>\textbf{(A)}\ 7 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 8 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 9 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ | ||

10 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 11</math> | 10 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 11</math> | ||

| − | ==Solution 1 ( | + | ==Solution 1 (Graph Theory)== |

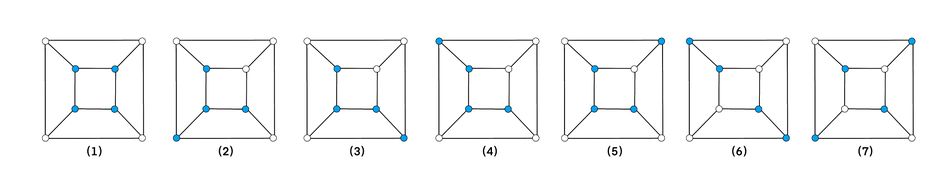

| − | + | This problem is about the relationships between the white unit cubes and the blue unit cubes, which can be solved by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_theory Graph Theory]. We use a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planar_graph Planar Graph] to represent the larger cube. Each vertex of the planar graph represents a unit cube. Each edge of the planar graph represents a shared face between <math>2</math> neighboring unit cubes. Each face of the planar graph represents a face of the larger cube. | |

| − | # '''Case 1: Each layer contains 2 cubes of each color.''' Note that we only need to consider the configuration of the white cubes because all the other cubes will be | + | Now the problem becomes a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_coloring Graph Coloring] problem of how many ways to assign <math>4</math> vertices blue and <math>4</math> vertices white with [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homeomorphism Topological Equivalence]. For example, in Figure <math>(1)</math>, as long as the <math>4</math> blue vertices belong to the same planar graph face, the different planar graphs are considered to be topological equivalent by rotating the larger cube. |

| − | ## '''Case 1.1: Both layers have 2 white cubes adjacent to each other.''' Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top edge of the front layer. Now, the white cubes in the back layer can be along the top, bottom, right, or left edges. | + | |

| − | ## '''Case 1.2: One layer has 2 white cubes adjacent to each other, and the other has 2 white cubes diagonal from each other.''' Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top of the front layer. The white cubes in the back layer can be at the top-left and bottom-right or at the top-right and bottom-left. If we rotate the | + | [[File:Topology.jpg | 950px]] |

| + | |||

| + | Here is how the <math>4</math> blue unit cubes are arranged: | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure <math>(1)</math>: <math>4</math> blue unit cubes are on the same layer (horizontal or vertical). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure <math>(2)</math>: <math>4</math> blue unit cubes are in <math>T</math> shape. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure <math>(3)</math> and <math>(4)</math>: <math>4</math> blue unit cubes are in <math>S</math> shape. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure <math>(5)</math>: <math>3</math> blue unit cubes are in <math>L</math> shape, and the other is isolated without a shared face. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure <math>(6)</math>: <math>2</math> pairs of neighboring blue unit cubes are isolated from each other without a shared face. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Figure <math>(7)</math>: <math>4</math> blue unit cubes are isolated from each other without a shared face. | ||

| + | |||

| + | So the answer is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)}\ 7}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~[https://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php/User:Isabelchen isabelchen] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 2 (Casework, Counting Down)== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let’s split the cube into two layers; a bottom and top. Note that there must be four of each color, so however many number of one color are in the bottom, there will be four minus that number of the color on the top. We do casework on the color distribution of the bottom layer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Case 1:''' 4, 0 | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this case, there is only one possibility for the top layer - all of the other color - <math>\binom{4}{4}</math>. Therefore there is 1 construction from this case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Case 2:''' 3, 1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this case, the top layer has four possibilities, because there are four different ways to arrange it so that it also has a 3, 1 color distribution - <math>\binom{4}{3}</math>. Therefore there are 4 constructions from this case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Case 3:''' 2, 2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this case, the top layer has six possibilities of arrangement - <math>\binom{4}{2}</math>. However, having adjacent colors one way can be rotated to having adjacent colors any other way, so there is only one construction for the adjacent colors subcase and similarly, only one for the diagonal color subcase. Therefore the total number of constructions for this case is 2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The total number of constructions for the cube is thus <math>1+4+2=7=\boxed{A}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~KingRavi | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 3 (Casework, Counting Up)== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Divide the <math>2 \times 2 \times 2</math> cube into two layers, say, front and back. Any possible construction can be rotated such that the front layer has the same or greater number of white cubes than blue cubes, so we only need to count the number of cases given that is true. | ||

| + | |||

| + | # '''Case 1: Each layer contains 2 cubes of each color.''' Note that we only need to consider the configuration of the white cubes because all the other cubes will be blue cubes. There are 2 ways that the 2 white cubes in each layer can be arranged: adjacent or diagonal to each other. | ||

| + | ## '''Case 1.1: Both layers have 2 white cubes adjacent to each other.''' Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top edge of the front layer. Now, the white cubes in the back layer can be along the top, bottom, right, or left edges. So, case 1.1 results in <math>4</math> constructions. | ||

| + | ## '''Case 1.2: One layer has 2 white cubes adjacent to each other, and the other has 2 white cubes diagonal from each other.''' Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top of the front layer. The white cubes in the back layer can be at the top-left and bottom-right or at the top-right and bottom-left. If we rotate the former case by 90 degrees clockwise into the page, it becomes the same as the latter case. So, case 1.2 results in <math>1</math> additional construction. | ||

## '''Case 1.3: Both layers have white cubes diagonal from each other.''' Rotate the cube such that there is a white cube at the top-left and bottom-right of the front layer. The back layer could also have white cubes at the top-left and bottom-right, but this is the same as case 1.1 with the white cubes in the back layer along the bottom edge. Alternatively, the back layer could have white cubes at the top-right and the bottom-left. This is a distinct case. So, case 1.3 results in <math>1</math> additional construction. | ## '''Case 1.3: Both layers have white cubes diagonal from each other.''' Rotate the cube such that there is a white cube at the top-left and bottom-right of the front layer. The back layer could also have white cubes at the top-left and bottom-right, but this is the same as case 1.1 with the white cubes in the back layer along the bottom edge. Alternatively, the back layer could have white cubes at the top-right and the bottom-left. This is a distinct case. So, case 1.3 results in <math>1</math> additional construction. | ||

## So, case 1 results in <math>4+1+1=6</math> distinct constructions. | ## So, case 1 results in <math>4+1+1=6</math> distinct constructions. | ||

| − | # '''Case 2: The front layer contains 3 white cubes.''' In this case, unless the sole | + | # '''Case 2: The front layer contains 3 white cubes, and the back layer contains one white cube.''' In this case, unless the sole white and sole blue cubes in the front and back layers are on opposite corners of the <math>2 \times 2 \times 2</math> cube, then that cube can be split into left and right layers with 2 cubes of each color in each layer. Those constructions were counted in case 1, so case 2 results in <math>1</math> additional construction. |

| − | # '''Case 3: The front layer contains 4 white cubes.''' | + | # '''Case 3: The front layer contains 4 white cubes, and the back layer contains no white cubes.''' If we split this construction into its left and right layers, then each layer will have 2 cubes of each color. So, this construction was counted in case 1, and case 3 results in <math>0</math> additional constructions. |

Therefore, our answer is <math>6+1+0=\boxed{\textbf{(A)}\ 7}</math>. | Therefore, our answer is <math>6+1+0=\boxed{\textbf{(A)}\ 7}</math>. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Solution 4 (Burnside Lemma)== |

| − | 1 | + | |

| + | Burnside lemma is used to counting number of orbit where the element on the same orbit can be achieved by the defined operator, naming rotation, reflection and etc. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The facts for Burnside lemma are | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. the sum of stabilizer on the same orbit equals to the # of operators; | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. the sum of stabilizer can be counted as <math>fix(g)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. the sum of the <math>fix(g)/|G|</math> equals the # of orbit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Let's start with defining the operator for a cube, | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. <math>\textbf{e (identity)}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For identity, there are <math>\frac{8!}{4!4!} = 70</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 2. <math>{\bf r^{1}, r^{2}, r^{3}}</math> to be the rotation axis along three pair of opposite face, | ||

| + | |||

| + | each contains <math>r^{i}_{90}, r^{i}_{180}, r^{i}_{270}</math> where <math>i= 1, 2, 3</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>fix(r^{i}_{90}) = fix(r^{i}_{270}) = 2\cdot1 = 2 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>fix(r^{i}_{180}) = \frac{4!}{2!\cdot2!} = 6 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | therefore <math>fix(\bf r^{i}) = 2+2+6 = 10 </math>, and <math>fix(\bf r^{1})+fix(\bf r^{2})+fix(\bf r^{3}) = 30 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 3. <math>{\bf r^{4}, r^{5}, r^{6}, r^{7}}</math> to the rotation axis along four cube diagonals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | each contains <math>r^{i}_{120}, r^{i}_{240}</math> where <math>i= 4, 5, 6, 7</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>fix(r^{i}_{120}) = fix(r^{i}_{240}) = 2\cdot1\cdot2\cdot1 = 4 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | therefore <math>fix(\bf r^{i}) = 4+4 = 8 </math>, and <math>fix(\bf r^{4})+fix(\bf r^{5})+fix(\bf r^{6})+fix(\bf r^{7}) = 32 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 4. <math>{\bf r^{8}, r^{9}, r^{10}, r^{11}, r^{12}, r^{13}}</math> to be the rotation axis along 6 pairs of diagonally opposite sides | ||

| + | |||

| + | each contains <math>r^{i}_{180}</math> where <math>i= 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>fix(r^{i}_{180}) = \frac{4!}{2!\cdot2!} = 6 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | therefore <math>fix(\bf r^{8})+fix(\bf r^{9})+fix(\bf r^{10})+fix(\bf r^{11})+fix(\bf r^{12})+fix(\bf r^{13}) = 36 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 5. The total number of operators are | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>|G| = 1 + 3\cdot3 + 4\cdot2 + 6\cdot1 = 24 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Based on 1, 2, 3, 4 the total number of stabilizers is | ||

| + | <math>70 + 30 + 32 + 36 = 168</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | therefore the number of orbits <math>= \frac{168}{G=24} = \boxed{7} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ~wwei.yu | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 5 (Quick 'n Easy but not rigorous)== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since rotations of a single pattern are considered indistinguishable, we can assume that the forward upper right corner of the 2-by-2-by-2 cube is a blue cube (since we can always rotate the big cube to place a blue cube in that spot). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once we've assigned this cube to be blue, we note that 3 1-by-1-by-1 cubes share a side with it, 3 1-by-1-by-1 cubes share a corner with it, and 1 1-by-1-by-1 cube does not touch the assigned cube at all, from the perspective of someone who can only see the cube's faces. We'll call the first 3 "adjacent", the second 3 "cornering", and the last one "opposite." | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can use a little bit of intuition to confirm that due to the rotation condition, we should treat all adjacents as indistinguishable, all cornerings as indistinguishable, and of course the opposite one is unique from all the others. Thus, we can list out like so (keeping in mind that there are 3 adjacents, 3 cornerings, and 1 opposite, and that we're choosing the positions of the remaining 3 blue cubes): | ||

| + | |||

| + | OAA, OAC, OCC, CCC, CAA, CCA, AAA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This gives the answer to be <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)}\ 7}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~ Curious_crow | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 1== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/Khnq5ZMTwXQ | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 2== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/Va_leSKAjRw | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Interstigation | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 3== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/nBL8mXHblHE | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~savannahsolver | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

{{AMC12 box|year=2021 Fall|ab=B|num-a=21|num-b=19}} | {{AMC12 box|year=2021 Fall|ab=B|num-a=21|num-b=19}} | ||

{{AMC10 box|year=2021 Fall|ab=B|num-a=25|num-b=23}} | {{AMC10 box|year=2021 Fall|ab=B|num-a=25|num-b=23}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Intermediate Combinatorics Problems]] | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:19, 15 September 2024

- The following problem is from both the 2021 Fall AMC 12B #20 and 2021 Fall AMC 10B #24, so both problems redirect to this page.

Contents

Problem

A cube is constructed from ![]() white unit cubes and

white unit cubes and ![]() blue unit cubes. How many different ways are there to construct the

blue unit cubes. How many different ways are there to construct the ![]() cube using these smaller cubes? (Two constructions are considered the same if one can be rotated to match the other.)

cube using these smaller cubes? (Two constructions are considered the same if one can be rotated to match the other.)

![]()

Solution 1 (Graph Theory)

This problem is about the relationships between the white unit cubes and the blue unit cubes, which can be solved by Graph Theory. We use a Planar Graph to represent the larger cube. Each vertex of the planar graph represents a unit cube. Each edge of the planar graph represents a shared face between ![]() neighboring unit cubes. Each face of the planar graph represents a face of the larger cube.

neighboring unit cubes. Each face of the planar graph represents a face of the larger cube.

Now the problem becomes a Graph Coloring problem of how many ways to assign ![]() vertices blue and

vertices blue and ![]() vertices white with Topological Equivalence. For example, in Figure

vertices white with Topological Equivalence. For example, in Figure ![]() , as long as the

, as long as the ![]() blue vertices belong to the same planar graph face, the different planar graphs are considered to be topological equivalent by rotating the larger cube.

blue vertices belong to the same planar graph face, the different planar graphs are considered to be topological equivalent by rotating the larger cube.

Here is how the ![]() blue unit cubes are arranged:

blue unit cubes are arranged:

In Figure ![]() :

: ![]() blue unit cubes are on the same layer (horizontal or vertical).

blue unit cubes are on the same layer (horizontal or vertical).

In Figure ![]() :

: ![]() blue unit cubes are in

blue unit cubes are in ![]() shape.

shape.

In Figure ![]() and

and ![]() :

: ![]() blue unit cubes are in

blue unit cubes are in ![]() shape.

shape.

In Figure ![]() :

: ![]() blue unit cubes are in

blue unit cubes are in ![]() shape, and the other is isolated without a shared face.

shape, and the other is isolated without a shared face.

In Figure ![]() :

: ![]() pairs of neighboring blue unit cubes are isolated from each other without a shared face.

pairs of neighboring blue unit cubes are isolated from each other without a shared face.

In Figure ![]() :

: ![]() blue unit cubes are isolated from each other without a shared face.

blue unit cubes are isolated from each other without a shared face.

So the answer is ![]()

Solution 2 (Casework, Counting Down)

Let’s split the cube into two layers; a bottom and top. Note that there must be four of each color, so however many number of one color are in the bottom, there will be four minus that number of the color on the top. We do casework on the color distribution of the bottom layer.

Case 1: 4, 0

In this case, there is only one possibility for the top layer - all of the other color - ![]() . Therefore there is 1 construction from this case.

. Therefore there is 1 construction from this case.

Case 2: 3, 1

In this case, the top layer has four possibilities, because there are four different ways to arrange it so that it also has a 3, 1 color distribution - ![]() . Therefore there are 4 constructions from this case.

. Therefore there are 4 constructions from this case.

Case 3: 2, 2

In this case, the top layer has six possibilities of arrangement - ![]() . However, having adjacent colors one way can be rotated to having adjacent colors any other way, so there is only one construction for the adjacent colors subcase and similarly, only one for the diagonal color subcase. Therefore the total number of constructions for this case is 2.

. However, having adjacent colors one way can be rotated to having adjacent colors any other way, so there is only one construction for the adjacent colors subcase and similarly, only one for the diagonal color subcase. Therefore the total number of constructions for this case is 2.

The total number of constructions for the cube is thus ![]()

~KingRavi

Solution 3 (Casework, Counting Up)

Divide the ![]() cube into two layers, say, front and back. Any possible construction can be rotated such that the front layer has the same or greater number of white cubes than blue cubes, so we only need to count the number of cases given that is true.

cube into two layers, say, front and back. Any possible construction can be rotated such that the front layer has the same or greater number of white cubes than blue cubes, so we only need to count the number of cases given that is true.

- Case 1: Each layer contains 2 cubes of each color. Note that we only need to consider the configuration of the white cubes because all the other cubes will be blue cubes. There are 2 ways that the 2 white cubes in each layer can be arranged: adjacent or diagonal to each other.

- Case 1.1: Both layers have 2 white cubes adjacent to each other. Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top edge of the front layer. Now, the white cubes in the back layer can be along the top, bottom, right, or left edges. So, case 1.1 results in

constructions.

constructions. - Case 1.2: One layer has 2 white cubes adjacent to each other, and the other has 2 white cubes diagonal from each other. Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top of the front layer. The white cubes in the back layer can be at the top-left and bottom-right or at the top-right and bottom-left. If we rotate the former case by 90 degrees clockwise into the page, it becomes the same as the latter case. So, case 1.2 results in

additional construction.

additional construction. - Case 1.3: Both layers have white cubes diagonal from each other. Rotate the cube such that there is a white cube at the top-left and bottom-right of the front layer. The back layer could also have white cubes at the top-left and bottom-right, but this is the same as case 1.1 with the white cubes in the back layer along the bottom edge. Alternatively, the back layer could have white cubes at the top-right and the bottom-left. This is a distinct case. So, case 1.3 results in

additional construction.

additional construction. - So, case 1 results in

distinct constructions.

distinct constructions.

- Case 1.1: Both layers have 2 white cubes adjacent to each other. Rotate the cube such that there are white cubes along the top edge of the front layer. Now, the white cubes in the back layer can be along the top, bottom, right, or left edges. So, case 1.1 results in

- Case 2: The front layer contains 3 white cubes, and the back layer contains one white cube. In this case, unless the sole white and sole blue cubes in the front and back layers are on opposite corners of the

cube, then that cube can be split into left and right layers with 2 cubes of each color in each layer. Those constructions were counted in case 1, so case 2 results in

cube, then that cube can be split into left and right layers with 2 cubes of each color in each layer. Those constructions were counted in case 1, so case 2 results in  additional construction.

additional construction. - Case 3: The front layer contains 4 white cubes, and the back layer contains no white cubes. If we split this construction into its left and right layers, then each layer will have 2 cubes of each color. So, this construction was counted in case 1, and case 3 results in

additional constructions.

additional constructions.

Therefore, our answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 4 (Burnside Lemma)

Burnside lemma is used to counting number of orbit where the element on the same orbit can be achieved by the defined operator, naming rotation, reflection and etc.

The facts for Burnside lemma are

1. the sum of stabilizer on the same orbit equals to the # of operators;

2. the sum of stabilizer can be counted as ![]()

3. the sum of the ![]() equals the # of orbit.

equals the # of orbit.

Let's start with defining the operator for a cube,

1. ![]()

For identity, there are ![]()

2. ![]() to be the rotation axis along three pair of opposite face,

to be the rotation axis along three pair of opposite face,

each contains ![]() where

where ![]()

![]()

![]()

therefore ![]() , and

, and ![]()

3. ![]() to the rotation axis along four cube diagonals.

to the rotation axis along four cube diagonals.

each contains ![]() where

where ![]()

![]()

therefore ![]() , and

, and ![]()

4. ![]() to be the rotation axis along 6 pairs of diagonally opposite sides

to be the rotation axis along 6 pairs of diagonally opposite sides

each contains ![]() where

where ![]()

![]()

therefore ![]()

5. The total number of operators are

![]()

Based on 1, 2, 3, 4 the total number of stabilizers is

![]()

therefore the number of orbits ![]()

~wwei.yu

Solution 5 (Quick 'n Easy but not rigorous)

Since rotations of a single pattern are considered indistinguishable, we can assume that the forward upper right corner of the 2-by-2-by-2 cube is a blue cube (since we can always rotate the big cube to place a blue cube in that spot).

Once we've assigned this cube to be blue, we note that 3 1-by-1-by-1 cubes share a side with it, 3 1-by-1-by-1 cubes share a corner with it, and 1 1-by-1-by-1 cube does not touch the assigned cube at all, from the perspective of someone who can only see the cube's faces. We'll call the first 3 "adjacent", the second 3 "cornering", and the last one "opposite."

We can use a little bit of intuition to confirm that due to the rotation condition, we should treat all adjacents as indistinguishable, all cornerings as indistinguishable, and of course the opposite one is unique from all the others. Thus, we can list out like so (keeping in mind that there are 3 adjacents, 3 cornerings, and 1 opposite, and that we're choosing the positions of the remaining 3 blue cubes):

OAA, OAC, OCC, CCC, CAA, CCA, AAA.

This gives the answer to be ![]() .

.

~ Curious_crow

Video Solution 1

Video Solution 2

~Interstigation

Video Solution 3

~savannahsolver

See Also

| 2021 Fall AMC 12B (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | |

| Preceded by Problem 19 |

Followed by Problem 21 |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 | |

| All AMC 12 Problems and Solutions | |

| 2021 Fall AMC 10B (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 23 |

Followed by Problem 25 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 | ||

| All AMC 10 Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.