Difference between revisions of "2020 AIME II Problems/Problem 13"

Topnotchmath (talk | contribs) m |

(→Solution 8 (The same circle)) |

||

| (58 intermediate revisions by 26 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Convex pentagon <math>ABCDE</math> has side lengths <math>AB=5</math>, <math>BC=CD=DE=6</math>, and <math>EA=7</math>. Moreover, the pentagon has an inscribed circle (a circle tangent to each side of the pentagon). Find the area of <math>ABCDE</math>. | Convex pentagon <math>ABCDE</math> has side lengths <math>AB=5</math>, <math>BC=CD=DE=6</math>, and <math>EA=7</math>. Moreover, the pentagon has an inscribed circle (a circle tangent to each side of the pentagon). Find the area of <math>ABCDE</math>. | ||

| − | + | ==Solution 1== | |

| − | == | + | Assume the incircle touches <math>AB</math>, <math>BC</math>, <math>CD</math>, <math>DE</math>, <math>EA</math> at <math>P,Q,R,S,T</math> respectively. Then let <math>PB=x=BQ=RD=SD</math>, <math>ET=y=ES=CR=CQ</math>, <math>AP=AT=z</math>. So we have <math>x+y=6</math>, <math>x+z=5</math> and <math>y+z</math>=7, solve it we have <math>x=2</math>, <math>z=3</math>, <math>y=4</math>. Let the center of the incircle be <math>I</math>, by SAS we can proof triangle <math>BIQ</math> is congruent to triangle <math>DIS</math>, and triangle <math>CIR</math> is congruent to triangle <math>SIE</math>. Then we have <math>\angle AED=\angle BCD</math>, <math>\angle ABC=\angle CDE</math>. Extend <math>CD</math>, cross ray <math>AB</math> at <math>M</math>, ray <math>AE</math> at <math>N</math>, then by AAS we have triangle <math>END</math> is congruent to triangle <math>BMC</math>. Thus <math>\angle M=\angle N</math>. Let <math>EN=MC=a</math>, then <math>BM=DN=a+2</math>. So by law of cosine in triangle <math>END</math> and triangle <math>ANM</math> we can obtain <cmath>\frac{2a+8}{2(a+7)}=\cos N=\frac{a^2+(a+2)^2-36}{2a(a+2)}</cmath>, solved it gives us <math>a=8</math>, which yield triangle <math>ANM</math> to be a triangle with side length 15, 15, 24, draw a height from <math>A</math> to <math>NM</math> divides it into two triangles with side lengths 9, 12, 15, so the area of triangle <math>ANM</math> is 108. Triangle <math>END</math> is a triangle with side lengths 6, 8, 10, so the area of two of them is 48, so the area of pentagon is <math>108-48=\boxed{60}</math>. |

| + | |||

| + | -Fanyuchen20020715 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 2 (Complex Bash)== | ||

| + | Suppose that the circle intersects <math>\overline{AB}</math>, <math>\overline{BC}</math>, <math>\overline{CD}</math>, <math>\overline{DE}</math>, and <math>\overline{EA}</math> at <math>P</math>, <math>Q</math>, <math>R</math>, <math>S</math>, and <math>T</math> respectively. Then <math>AT = AP = a</math>, <math>BP = BQ = b</math>, <math>CQ = CR = c</math>, <math>DR = DS = d</math>, and <math>ES = ET = e</math>. So <math>a + b = 5</math>, <math>b + c = 6</math>, <math>c + d = 6</math>, <math>d + e = 6</math>, and <math>e + a = 7</math>. Then <math>2a + 2b + 2c + 2d + 2e = 30</math>, so <math>a + b + c + d + e= 15</math>. Then we can solve for each individually. <math>a = 3</math>, <math>b = 2</math>, <math>c = 4</math>, <math>d = 2</math>, and <math>e = 4</math>. To find the radius, we notice that <math>4 \arctan(\frac{2}{r}) + 4 \arctan(\frac{4}{r}) + 2 \arctan (\frac{3}{r}) = 360 ^ \circ</math>, or <math>2 \arctan(\frac{2}{r}) + 2 \arctan(\frac{4}{r}) + \arctan (\frac{3}{r}) = 180 ^ \circ</math>. Each of these angles in this could be represented by complex numbers. When two complex numbers are multiplied, their angles add up to create the angle of the resulting complex number. Thus, <math>(r + 2i)^2 \cdot (r + 4i)^2 \cdot (r + 3i)</math> is real. Expanding, we get: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(r^2 + 4ir - 4)(r^2 + 8ir -16)(r + 3i)</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(r^4 + 12ir^3 - 52r^2 - 96ir + 64)(r + 3i)</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the last expanding, we only multiply the reals with the imaginaries and vice versa, because we only care that the imaginary component equals 0. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>15ir^4 - 252ir^2 + 192i = 0</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>5r^4 - 84r^2 + 64 = 0</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(5r^2 - 4)(r^2 - 16) = 0</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>r</math> must equal 4, as r cannot be negative or be approximately equal to 1. | ||

| + | Thus, the area of <math>ABCDE</math> is <math>4 \cdot (a + b + c + d + e) = 4 \cdot 15 = \boxed{60}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | -nihao4112 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 3 (Guess 1)== | ||

| + | This pentagon is very close to a regular pentagon with side lengths <math>6</math>. The area of a regular pentagon with side lengths <math>s</math> is <math>\frac{5s^2}{4\sqrt{5-2\sqrt{5}}}</math>. <math>5-2\sqrt{5}</math> is slightly greater than <math>\frac{1}{2}</math> given that <math>2\sqrt{5}</math> is slightly less than <math>\frac{9}{2}</math>. <math>4\sqrt{5-2\sqrt{5}}</math> is then slightly greater than <math>2\sqrt{2}</math>. We will approximate that to be <math>2.9</math>. The area is now roughly <math>\frac{180}{2.9}</math>, but because the actual pentagon is not regular, but has the same perimeter of the regular one that we are comparing to we can say that this is an overestimate on the area and turn the <math>2.9</math> into <math>3</math> thus turning the area into <math>\frac{180}{3}</math> which is <math>60</math> and since <math>60</math> is a multiple of the semiperimeter <math>15</math>, we can safely say that the answer is most likely <math>\boxed{60}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Lopkiloinm | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 4 (Guess 2)== | ||

| + | Because the AIME answers have to be a whole number it would meant the radius of the circle have to be a whole number, thus by drawing the diagram and experimenting, we can safely say the radius is 4 and the answer is 60 | ||

| + | |||

| + | (Edit: While the guess would be technically correct, the assumption that the radius would have to be a whole number for the ans to be a whole number is wrong) | ||

| + | |||

| + | By EtherealMidnight | ||

| + | |||

| + | (Edit: I think that will actually work because the area of <math>ABCDE</math> is equal to the semi-perimeter times the radius. By a simple calculation, we know that the semi-perimeter is an integer so the radius should also be an integer) | ||

| + | |||

| + | By YBSuburbanTea | ||

| + | |||

| + | ...the radius could be a fraction with denominator 3, 5, or 15, and the area of the pentagon would still be an integer. - GeometryJake | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 5 (Official MAA 1)== | ||

| + | Let <math>\omega</math> be the inscribed circle, <math>I</math> be its center, and <math>r</math> be its radius. The area of <math>ABCDE</math> is equal to its semiperimeter, <math>15,</math> times <math>r</math>, so the problem is reduced to finding <math>r</math>. Let <math>a</math> be the length of the tangent segment from <math>A</math> to <math>\omega</math>, and analogously define <math>b</math>, <math>c</math>, <math>d</math>, and <math>e</math>. Then <math>a+b=5</math>, <math>b+c= c+d=d+e=6</math>, and <math>e+a=7</math>, with a total of <math>a+b+c+d+e=15</math>. Hence <math>a=3</math>, <math>b=d=2</math>, and <math>c=e=4</math>. It follows that <math>\angle B= \angle D</math> and <math>\angle C= \angle E</math>. Let <math>Q</math> be the point where <math>\omega</math> is tangent to <math>\overline{CD}</math>. Then <math>\angle IAE = \angle IAB =\frac{1}{2}\angle A</math>. Now we claim that points <math>A, I, Q</math> are collinear, which can be proved if <math>\angle{AIQ}=\angle{QIA}=180^{\circ}</math>. The sum of the internal angles in polygons <math>ABCQI</math> and <math>AIQDE</math> are equal, so <math>\angle IAE + \angle AIQ + \angle IQD + \angle D + \angle E = \angle IAB + \angle B + \angle C + \angle CQI + \angle QIA</math>, which implies that <math>\angle AIQ</math> must be <math>180^\circ</math>. Therefore points <math>A</math>, <math>I</math>, and <math>Q</math> are collinear. | ||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | defaultpen(fontsize(8pt)); | ||

| + | unitsize(0.025cm); | ||

| + | |||

| + | pair[] vertices = {(0,0), (5,0), (8.6,4.8), (3.8,8.4), (-1.96, 6.72)}; | ||

| + | string[] labels = {"$A$", "$B$", "$C$", "$D$", "$E$"}; | ||

| + | pair[] dirs = {SW, SE,E, N, NW}; | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | string[] smallLabels = {"$a$", "$b$", "$c$", "$d$", "$e$"}; | ||

| + | |||

| + | pair I = (3,4); | ||

| + | real rad = 4; | ||

| + | pair Q = foot(I, vertices[2], vertices[3]); | ||

| + | |||

| + | pair[] interpoints = {}; | ||

| + | for(int i =0; i<vertices.length; ++i){ | ||

| + | interpoints.push(foot(I, vertices[i], vertices[(i+1)%vertices.length])); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | for(int i = 0; i< vertices.length; ++i){ | ||

| + | draw(vertices[i]--vertices[(i+1)%vertices.length]); | ||

| + | dot(labels[i],vertices[i],dirs[i]); | ||

| + | draw(I--vertices[i]); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | draw(Circle(I, rad)); | ||

| + | dot("$I$", I, dir(200)); | ||

| + | draw(I--Q); | ||

| + | dot("$Q$", Q, NE); | ||

| + | |||

| + | for(int i = 0; i < vertices.length; ++i){ | ||

| + | label(smallLabels[i], vertices[i] --interpoints[i]); | ||

| + | //dot(interpoints[i], blue); | ||

| + | label(smallLabels[i], interpoints[(i-1)%vertices.length] -- vertices[i]); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | |||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | Because <math>\overline{AQ} \perp \overline{CD}</math>, it follows that<cmath>AC^2-AD^2=CQ^2-DQ^2=c^2-d^2=12.</cmath>Another expression for <math>AC^2-AD^2</math> can be found as follows. Note that <math>\tan \left(\frac{\angle B}{2}\right) = \frac{r}{2}</math> and <math>\tan \left(\frac{\angle E}{2}\right) = \frac{r}{4}</math>, so | ||

| + | <cmath>\cos (\angle B) =\frac{1-\tan^2 \left(\frac{\angle B}{2}\right)}{1+\tan^2 \left(\frac{\angle B}{2}\right)} = \frac{4-r^2}{4+r^2}</cmath>and | ||

| + | <cmath>\cos (\angle E) = \frac{1-\tan^2 \left(\frac{\angle E}{2}\right)}{1+\tan^2 \left(\frac{\angle E}{2}\right)}= \frac{16-r^2}{16+r^2}.</cmath>Applying the Law of Cosines to <math>\triangle ABC</math> and <math>\triangle AED</math> gives | ||

| + | <cmath>AC^2=AB^2+BC^2-2\cdot AB\cdot BC\cdot \cos (\angle B) = 5^2+6^2-2 \cdot 5 \cdot 6 \cdot \frac{4-r^2}{4+r^2}</cmath> | ||

| + | and | ||

| + | <cmath>AD^2=AE^2+DE^2-2 \cdot AE \cdot DE \cdot \cos(\angle E) = 7^2+6^2-2 \cdot 7 \cdot 6 \cdot \frac{16-r^2}{16+r^2}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Hence | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>12=AC^2- AD^2= 5^2-2\cdot 5 \cdot 6\cdot \frac{4-r^2}{4+r^2} -7^2+2\cdot 7 \cdot 6 \cdot \frac{16-r^2}{16+r^2},</cmath> | ||

| + | yielding | ||

| + | <cmath>2\cdot 7 \cdot 6 \cdot \frac{16-r^2}{16+r^2}- 2\cdot 5 \cdot 6\cdot \frac{4-r^2}{4+r^2}= 36;</cmath> | ||

| + | equivalently | ||

| + | <cmath>7(16-r^2)(4+r^2)-5(4-r^2)(16+r^2) = 3(16+r^2)(4+r^2).</cmath> | ||

| + | Substituting <math>x=r^2</math> gives the quadratic equation <math>5x^2-84x+64=0</math>, with solutions <math>\frac{42 - 38}{5}=\frac45</math>, and <math>\frac{42 + 38}{5}= 16</math>. The solution <math>r^2=\frac45</math> corresponds to a five-pointed star, which is not convex. Indeed, if <math>r<3</math>, then <math> \tan \left(\frac{\angle A}{2}\right)</math>, <math>\tan \left(\frac{\angle C}{2}\right)</math>, and <math>\tan \left(\frac{\angle E}{2}\right)</math> are less than <math>1,</math> implying that <math>\angle A</math>, <math>\angle C</math>, and <math>\angle E</math> are acute, which cannot happen in a convex pentagon. Thus <math>r^2=16</math> and <math>r=4</math>. The requested area is <math>15\cdot4 = \boxed{60}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 6 (Official MAA 2)== | ||

| + | Define <math>a</math>, <math>b</math>, <math>c</math>, <math>d</math>, <math>e</math>, and <math>r</math> as in Solution 5. Then, as in Solution 5, <math>a=3</math>, <math>b=d=2</math>, <math>c=e=4</math>, <math>\angle B= \angle D</math>, and <math>\angle C= \angle E</math>. Let <math>\alpha =\frac{\angle A}{2}</math>, <math>\beta = \frac{\angle B}{2}</math>, and <math>\gamma=\frac{\angle C}{2}</math>. It follows that <math>540^{\circ} = 2\alpha + 4 \beta + 4 \gamma</math>, so <math>270^{\circ} = \alpha + 2\beta + 2 \gamma</math>. Thus | ||

| + | <cmath>\tan(2\beta + 2 \gamma) = \frac{1}{\tan \alpha},</cmath> | ||

| + | <math>\tan(\beta) = \frac{r}{2}</math>, <math>\tan(\gamma) = \frac{r}{4}</math>, and <math>\tan(\alpha) = \frac {r}{3}</math>. By the Tangent Addition Formula, | ||

| + | <cmath>\tan(\beta +\gamma) = \frac{6r}{8-r^2}</cmath> | ||

| + | and | ||

| + | <cmath>\tan(2\beta + 2\gamma) = \frac{\frac{12r}{8-r^2}}{1-\frac{36r^2}{(8-r^2)^2}} = \frac{12r(8-r^2)}{(8-r^2)^2-36r^2}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Therefore | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{12r(8-r^2)}{(8-r^2)^2-36r^2} = \frac{3}{r},</cmath> | ||

| + | which simplifies to <math>5r^4 - 84r^2 + 64 = 0</math>. Then the solution proceeds as in Solution 5. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 7 (Official MAA 3)== | ||

| + | Define <math>a</math>, <math>b</math>, <math>c</math>, <math>d</math>, <math>e</math>, and <math>r</math> as in Solution 5. Note that | ||

| + | <cmath>\arctan\left(\frac{a}{r}\right) + \arctan\left(\frac{b}{r}\right) + \arctan\left(\frac{c}{r}\right) + \arctan\left(\frac{d}{r}\right) + \arctan\left(\frac{e}{r}\right) = 180^{\circ}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Hence | ||

| + | <cmath>\operatorname{Arg}(r + 3i) + 2\cdot \operatorname{Arg}(r + 2i) + 2\cdot \operatorname{Arg}(r + 4i) = 180^{\circ}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Therefore | ||

| + | <cmath>\operatorname{Im} \big( (r + 3i)(r+2i)^2(r+4i)^2 \big) = 0.</cmath> | ||

| + | Simplifying this equation gives the same quadratic equation in <math>r^2</math> as in Solution 5. | ||

| + | |||

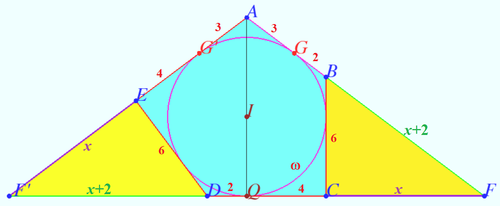

| + | ==Solution 8 (The same circle)== | ||

| + | [[File:2020 AIME II 13.png|500px|right]] | ||

| + | Notation shown on diagram. As in solution 5, we get <math>\overline{AQ} \perp \overline{CD}, AG = 3, GB = 2, CQ = 4</math> and so on. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math> \overline{AB}</math> cross <math> \overline{CD}</math> at <math>F, \overline{AE}</math> cross <math> \overline{CD}</math> at <math>F', CF = x.</math> | ||

| + | <math>FQ = FG \implies FB = x+2.</math> | ||

| + | <math>\angle BAQ = \angle EAQ \implies DF' = x + 2, EF' = x.</math> | ||

| + | Triangle <math>\triangle AFF'</math> has semiperimeter <math>s = 2x + 11.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The radius of <i><b>incircle</b></i> <math>\omega</math> is | ||

| + | <math>r =\sqrt{\frac{s-FF’}{s}}(s-AF) = \sqrt{\frac{3}{2x +11}}(x+4). </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Triangle <math>\triangle BCF</math> has semiperimeter <math>s = x + 4.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The radius of <i><b>excircle </b></i> <math>\omega</math> is | ||

| + | <math>r = \sqrt{\frac{s(s-BF)(s-CF)}{s-BC}} = \sqrt{ \frac{(x+4)\cdot 2 \cdot 4}{x - 2}}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is the same radius, therefore | ||

| + | <cmath> \sqrt{\frac{3}{2x +11}}(x+4) = \sqrt{\frac{8(x+4)}{x – 2}} \implies \frac {3(x+4)}{2x+11} = \frac {8}{x-2} \implies (x-8)(3x + 14) = 0 \implies x = 8, r = 4.</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then the solution proceeds as in Solution 5. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 1 by MOP 2024== | ||

| + | https://youtube.com/watch?v=BXEXcCNXrlM | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~r00tsOfUnity | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 2== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/bz5N-jI2e0U?t=327 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 3== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/_fwkGTdMd8U | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution 4== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/kn3c2LStiHA | ||

| + | (solve in 5 minutes) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~MathProblemSolvingSkills.com | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{{AIME box|year=2020|n=II|num-b=12|num-a=14}} | {{AIME box|year=2020|n=II|num-b=12|num-a=14}} | ||

| + | [[Category: Intermediate Geometry Problems]] | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:00, 8 January 2024

Contents

- 1 Problem

- 2 Solution 1

- 3 Solution 2 (Complex Bash)

- 4 Solution 3 (Guess 1)

- 5 Solution 4 (Guess 2)

- 6 Solution 5 (Official MAA 1)

- 7 Solution 6 (Official MAA 2)

- 8 Solution 7 (Official MAA 3)

- 9 Solution 8 (The same circle)

- 10 Video Solution 1 by MOP 2024

- 11 Video Solution 2

- 12 Video Solution 3

- 13 Video Solution 4

Problem

Convex pentagon ![]() has side lengths

has side lengths ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Moreover, the pentagon has an inscribed circle (a circle tangent to each side of the pentagon). Find the area of

. Moreover, the pentagon has an inscribed circle (a circle tangent to each side of the pentagon). Find the area of ![]() .

.

Solution 1

Assume the incircle touches ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() at

at ![]() respectively. Then let

respectively. Then let ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() . So we have

. So we have ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() =7, solve it we have

=7, solve it we have ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() . Let the center of the incircle be

. Let the center of the incircle be ![]() , by SAS we can proof triangle

, by SAS we can proof triangle ![]() is congruent to triangle

is congruent to triangle ![]() , and triangle

, and triangle ![]() is congruent to triangle

is congruent to triangle ![]() . Then we have

. Then we have ![]() ,

, ![]() . Extend

. Extend ![]() , cross ray

, cross ray ![]() at

at ![]() , ray

, ray ![]() at

at ![]() , then by AAS we have triangle

, then by AAS we have triangle ![]() is congruent to triangle

is congruent to triangle ![]() . Thus

. Thus ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() , then

, then ![]() . So by law of cosine in triangle

. So by law of cosine in triangle ![]() and triangle

and triangle ![]() we can obtain

we can obtain ![]() , solved it gives us

, solved it gives us ![]() , which yield triangle

, which yield triangle ![]() to be a triangle with side length 15, 15, 24, draw a height from

to be a triangle with side length 15, 15, 24, draw a height from ![]() to

to ![]() divides it into two triangles with side lengths 9, 12, 15, so the area of triangle

divides it into two triangles with side lengths 9, 12, 15, so the area of triangle ![]() is 108. Triangle

is 108. Triangle ![]() is a triangle with side lengths 6, 8, 10, so the area of two of them is 48, so the area of pentagon is

is a triangle with side lengths 6, 8, 10, so the area of two of them is 48, so the area of pentagon is ![]() .

.

-Fanyuchen20020715

Solution 2 (Complex Bash)

Suppose that the circle intersects ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() at

at ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() respectively. Then

respectively. Then ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . So

. So ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Then we can solve for each individually.

. Then we can solve for each individually. ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . To find the radius, we notice that

. To find the radius, we notice that ![]() , or

, or ![]() . Each of these angles in this could be represented by complex numbers. When two complex numbers are multiplied, their angles add up to create the angle of the resulting complex number. Thus,

. Each of these angles in this could be represented by complex numbers. When two complex numbers are multiplied, their angles add up to create the angle of the resulting complex number. Thus, ![]() is real. Expanding, we get:

is real. Expanding, we get:

![]()

![]()

On the last expanding, we only multiply the reals with the imaginaries and vice versa, because we only care that the imaginary component equals 0.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() must equal 4, as r cannot be negative or be approximately equal to 1.

Thus, the area of

must equal 4, as r cannot be negative or be approximately equal to 1.

Thus, the area of ![]() is

is ![]()

-nihao4112

Solution 3 (Guess 1)

This pentagon is very close to a regular pentagon with side lengths ![]() . The area of a regular pentagon with side lengths

. The area of a regular pentagon with side lengths ![]() is

is ![]() .

. ![]() is slightly greater than

is slightly greater than ![]() given that

given that ![]() is slightly less than

is slightly less than ![]() .

. ![]() is then slightly greater than

is then slightly greater than ![]() . We will approximate that to be

. We will approximate that to be ![]() . The area is now roughly

. The area is now roughly ![]() , but because the actual pentagon is not regular, but has the same perimeter of the regular one that we are comparing to we can say that this is an overestimate on the area and turn the

, but because the actual pentagon is not regular, but has the same perimeter of the regular one that we are comparing to we can say that this is an overestimate on the area and turn the ![]() into

into ![]() thus turning the area into

thus turning the area into ![]() which is

which is ![]() and since

and since ![]() is a multiple of the semiperimeter

is a multiple of the semiperimeter ![]() , we can safely say that the answer is most likely

, we can safely say that the answer is most likely ![]() .

.

~Lopkiloinm

Solution 4 (Guess 2)

Because the AIME answers have to be a whole number it would meant the radius of the circle have to be a whole number, thus by drawing the diagram and experimenting, we can safely say the radius is 4 and the answer is 60

(Edit: While the guess would be technically correct, the assumption that the radius would have to be a whole number for the ans to be a whole number is wrong)

By EtherealMidnight

(Edit: I think that will actually work because the area of ![]() is equal to the semi-perimeter times the radius. By a simple calculation, we know that the semi-perimeter is an integer so the radius should also be an integer)

is equal to the semi-perimeter times the radius. By a simple calculation, we know that the semi-perimeter is an integer so the radius should also be an integer)

By YBSuburbanTea

...the radius could be a fraction with denominator 3, 5, or 15, and the area of the pentagon would still be an integer. - GeometryJake

Solution 5 (Official MAA 1)

Let ![]() be the inscribed circle,

be the inscribed circle, ![]() be its center, and

be its center, and ![]() be its radius. The area of

be its radius. The area of ![]() is equal to its semiperimeter,

is equal to its semiperimeter, ![]() times

times ![]() , so the problem is reduced to finding

, so the problem is reduced to finding ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the length of the tangent segment from

be the length of the tangent segment from ![]() to

to ![]() , and analogously define

, and analogously define ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , with a total of

, with a total of ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() and

and ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the point where

be the point where ![]() is tangent to

is tangent to ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() . Now we claim that points

. Now we claim that points ![]() are collinear, which can be proved if

are collinear, which can be proved if ![]() . The sum of the internal angles in polygons

. The sum of the internal angles in polygons ![]() and

and ![]() are equal, so

are equal, so ![]() , which implies that

, which implies that ![]() must be

must be ![]() . Therefore points

. Therefore points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are collinear.

are collinear.

![[asy] defaultpen(fontsize(8pt)); unitsize(0.025cm); pair[] vertices = {(0,0), (5,0), (8.6,4.8), (3.8,8.4), (-1.96, 6.72)}; string[] labels = {"$A$", "$B$", "$C$", "$D$", "$E$"}; pair[] dirs = {SW, SE,E, N, NW}; string[] smallLabels = {"$a$", "$b$", "$c$", "$d$", "$e$"}; pair I = (3,4); real rad = 4; pair Q = foot(I, vertices[2], vertices[3]); pair[] interpoints = {}; for(int i =0; i<vertices.length; ++i){ interpoints.push(foot(I, vertices[i], vertices[(i+1)%vertices.length])); } for(int i = 0; i< vertices.length; ++i){ draw(vertices[i]--vertices[(i+1)%vertices.length]); dot(labels[i],vertices[i],dirs[i]); draw(I--vertices[i]); } draw(Circle(I, rad)); dot("$I$", I, dir(200)); draw(I--Q); dot("$Q$", Q, NE); for(int i = 0; i < vertices.length; ++i){ label(smallLabels[i], vertices[i] --interpoints[i]); //dot(interpoints[i], blue); label(smallLabels[i], interpoints[(i-1)%vertices.length] -- vertices[i]); } [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/0/4/9/049059ae12c804f8c02f35d5ccc0c92683085c54.png) Because

Because ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that![]() Another expression for

Another expression for ![]() can be found as follows. Note that

can be found as follows. Note that ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so

![]() and

and

![]() Applying the Law of Cosines to

Applying the Law of Cosines to ![]() and

and ![]() gives

gives

![]() and

and

![]() Hence

Hence

![]() yielding

yielding

![]() equivalently

equivalently

![]() Substituting

Substituting ![]() gives the quadratic equation

gives the quadratic equation ![]() , with solutions

, with solutions ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The solution

. The solution ![]() corresponds to a five-pointed star, which is not convex. Indeed, if

corresponds to a five-pointed star, which is not convex. Indeed, if ![]() , then

, then ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are less than

are less than ![]() implying that

implying that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are acute, which cannot happen in a convex pentagon. Thus

are acute, which cannot happen in a convex pentagon. Thus ![]() and

and ![]() . The requested area is

. The requested area is ![]() .

.

Solution 6 (Official MAA 2)

Define ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() as in Solution 5. Then, as in Solution 5,

as in Solution 5. Then, as in Solution 5, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Thus

. Thus

![]()

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . By the Tangent Addition Formula,

. By the Tangent Addition Formula,

![]() and

and

![\[\tan(2\beta + 2\gamma) = \frac{\frac{12r}{8-r^2}}{1-\frac{36r^2}{(8-r^2)^2}} = \frac{12r(8-r^2)}{(8-r^2)^2-36r^2}.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/4/e/f/4ef015648462c699b9612d9bf6515c2be8d22276.png) Therefore

Therefore

![]() which simplifies to

which simplifies to ![]() . Then the solution proceeds as in Solution 5.

. Then the solution proceeds as in Solution 5.

Solution 7 (Official MAA 3)

Define ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() as in Solution 5. Note that

as in Solution 5. Note that

![]() Hence

Hence

![]() Therefore

Therefore

![]() Simplifying this equation gives the same quadratic equation in

Simplifying this equation gives the same quadratic equation in ![]() as in Solution 5.

as in Solution 5.

Solution 8 (The same circle)

Notation shown on diagram. As in solution 5, we get ![]() and so on.

and so on.

Let ![]() cross

cross ![]() at

at ![]() cross

cross ![]() at

at ![]()

![]()

![]() Triangle

Triangle ![]() has semiperimeter

has semiperimeter ![]()

The radius of incircle ![]() is

is

![]()

Triangle ![]() has semiperimeter

has semiperimeter ![]()

The radius of excircle ![]() is

is

It is the same radius, therefore

![]()

Then the solution proceeds as in Solution 5.

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

Video Solution 1 by MOP 2024

https://youtube.com/watch?v=BXEXcCNXrlM

~r00tsOfUnity

Video Solution 2

https://youtu.be/bz5N-jI2e0U?t=327

Video Solution 3

Video Solution 4

https://youtu.be/kn3c2LStiHA (solve in 5 minutes)

~MathProblemSolvingSkills.com

| 2020 AIME II (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 12 |

Followed by Problem 14 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.