Difference between revisions of "Basic Programming With Python"

m (→Program Example 6: congrats added) |

(→Overloading) |

||

| (96 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Important: It is extremely recommended that you read [[Getting Started With Python Programming]] before reading this unless you already know some programming knowledge.''' | '''Important: It is extremely recommended that you read [[Getting Started With Python Programming]] before reading this unless you already know some programming knowledge.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | (Note: This is a really long article. To learn the most from this article, you need to read everything in order and skip nothing, unless you are '''absolutely absolutely sure that that content is way too easy for you.''') | ||

This article will talk about some basic Python programming. If you don't even know how to install Python, look [[Getting Started With Python Programming|here]]. | This article will talk about some basic Python programming. If you don't even know how to install Python, look [[Getting Started With Python Programming|here]]. | ||

| + | Note that this article has lots of program examples. It is recommended (but not required) to try these on your own before looking at the solutions. | ||

| + | ==Booleans== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Print all two-digit positive integers <math>\boldsymbol{x}</math> such that <math>\boldsymbol{5x}</math> is a two-digit positive integer.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can create a function with our previous code. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We will have to slightly modify our function so we can use it in a for loop at the end: | ||

| + | |||

| + | def check(x): | ||

| + | if x*5 > 9 and x*5 < 100: | ||

| + | return True | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | return False | ||

| + | |||

| + | True and False are what are called '''booleans'''. When an if or elif statement receives True, the code inside of the statement happens. When an if or elif statement receives False, the code inside of the statement does not happen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We must create a for loop that will iterate through all two digit positive integers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | def check(x): | ||

| + | if x*5 > 9 and x*5 < 100: | ||

| + | return True | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | return False | ||

| + | for i in range(10,100): | ||

| + | if check(i): | ||

| + | print(i) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The final for loop checks if <math>5i</math> is a two digit integer. If it is, the function returns True and the code inside the if statement gets run. If it isn't, the function returns False and the code inside the if statement gets ignored. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If we run this, we will get the answer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All two digit integers from 10 to 19 inclusive work! | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Flow== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Flow consists of if statements, elif (else if) statements, and else statements. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *An if statement checks if a comparison is true. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *An else statement checks if a comparison is not true. It is used after an if statement (and all elif statements after the if statement) and it shares the same comparison as the if statement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *An elif statement checks for two things: if a comparison is true, and if a comparison is not true. It is used right after the if statement. | ||

| + | ===Program Example=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''if you multiply 10 by 5, do you get a two digit number?''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | This problem is super easy to solve without a program, but let's write a program to solve this anyway. We will use an if statement to check if <math>10\cdot 5</math> is less than 100 and greater than 9. | ||

| + | |||

| + | if 10*5 > 9: | ||

| + | if 10*5 < 100: | ||

| + | print("Yes") | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | print("No") | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | print("No") | ||

| + | |||

| + | This code means, if 10*5 > 9, then we will check if it is less than 100. If it is not greater than 9, however, we will print No. If it is greater than 9, we check if it is less than 100. If it is, we print Yes. If it isn't we print No. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These nested if statements can be very confusing. Luckily, there is a faster an easier way to do this. | ||

| + | |||

| + | if 10*5 > 9 and 10*5 < 100: | ||

| + | print("Yes") | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | print("No") | ||

| + | |||

| + | This code checks for the two conditions at the same time. If we run it, we get our answer of Yes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Always remember; the simpler your code is the better it will preform! | ||

==Loops== | ==Loops== | ||

| Line 15: | Line 88: | ||

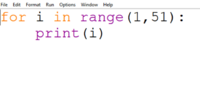

[[File:Capture.PNG|200px]] | [[File:Capture.PNG|200px]] | ||

| − | This for loop iterates over the list of integers from 1 to 51, | + | This for loop iterates over the list of integers from 1 to 51, but excludes 51. This is because python will always think of the last number as a barrier and the number before as the stopping point; Python will count the 1st number though as it is the starting point. That means it is a list from 1 to 50, inclusive. On every iteration, Python will print the number that the loop is iterating through. |

For example, in the first iteration, i = 1, so Python prints 1. | For example, in the first iteration, i = 1, so Python prints 1. | ||

| Line 22: | Line 95: | ||

This continues so on until the number, 50, is reached. Therefore, the last number Python will print out is 50. | This continues so on until the number, 50, is reached. Therefore, the last number Python will print out is 50. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We call the range function a generator because it returns a list (find out more in the later section!). When we do | ||

| + | for i in something | ||

| + | the something is an iterable object (string, list, tuple, so on). The variable i is just an item! | ||

====Program Example==== | ====Program Example==== | ||

| − | '''Find <math>\sum_{n=1}^{50} 2^{n}.</math>''' | + | '''Find <math>\boldsymbol{\sum_{n=1}^{50} 2^{n}.}</math>''' |

To do this task, we must create a for loop and loop over the integers from 1 to 50 inclusive: | To do this task, we must create a for loop and loop over the integers from 1 to 50 inclusive: | ||

| − | + | for i in range(1,51): | |

| − | |||

| − | for i in range(1,51): | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Now what? We must keep a running total and increase it by <math>2^i</math> every time: | Now what? We must keep a running total and increase it by <math>2^i</math> every time: | ||

| − | + | total = 0 | |

| − | + | for i in range(1,51): | |

| − | total = 0 | + | total += 2**i |

| − | |||

| − | for i in range(1,51): | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

We must not forget to print the total at the end! | We must not forget to print the total at the end! | ||

| − | + | total = 0 | |

| − | + | for i in range(1,51): | |

| − | total = 0 | + | total += 2**i |

| − | + | print(total) | |

| − | for i in range(1,51): | ||

| − | |||

| − | print(total) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

You must exit out of the for loop one you reach the print(total) line by pressing backspace. | You must exit out of the for loop one you reach the print(total) line by pressing backspace. | ||

| − | Once you run your program, you should get an answer of <math>\boxed{2,251,799,813,685,246.}</math> | + | Once you run your program, you should get an answer of <math>\boxed{2,\! 251, \! 799,\! 813, \! 685,\!246.}</math> |

===The While Loop=== | ===The While Loop=== | ||

| Line 66: | Line 129: | ||

While loops don't loop over a list. They loop over and over and over...'''until'''...a condition becomes false. | While loops don't loop over a list. They loop over and over and over...'''until'''...a condition becomes false. | ||

| + | i = 10 | ||

| + | total = 0 | ||

| + | while i < 1000: | ||

| + | total += i | ||

| + | i += 10 | ||

| + | print(total) | ||

| − | < | + | In this code, the while loop loops 100 times, until <math>i</math> becomes greater than or equal to 1000. |

| − | i | ||

| − | + | ====Program Example==== | |

| − | + | '''Find <math>\boldsymbol{\sum_{n=1}^{50} 2^n}</math> using a while loop.''' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| + | We must create a while loop that will iterate until n is greater than <math>50.</math> | ||

| − | + | n = 1 | |

| + | total = 0 | ||

| + | while n <= 50: | ||

| + | total += 2**n | ||

| + | n += 1 | ||

| + | print(total) | ||

| − | = | + | We must not forget to include the n += 1 line at the end of the while loop! |

| − | + | If we run this, we will get the same answer as last time, <math>2,251,799,813,685,246.</math> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Notes/key | ||

| − | < | + | -just for any one who forgot, <= means less than or equal |

| − | |||

| − | + | -The double ** means "too the power of" as in 5**2 = 25, in this program (it can have other meanings with different key phrases) | |

| − | + | - += This operator means increment. For example 2 += 5 gives seven. This is one of the assigment operators[https://www.w3schools.com/python/gloss_python_assignment_operators.asp] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | (To anyone who is annoyed that I'm writing these notes, I'm sorry and all, but this text book does not seem to have much basic explanation, so I'm adding some.) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Functions== | ==Functions== | ||

| Line 113: | Line 175: | ||

===Program Example 1=== | ===Program Example 1=== | ||

| − | '''Find <math>[2 \uparrow \downarrow (1 \uparrow \downarrow 2)] \uparrow \downarrow 2.</math>''' | + | '''Find <math>\boldsymbol{[2 \uparrow \downarrow (1 \uparrow \downarrow 2)] \uparrow \downarrow 2.}</math>''' |

We know this will be a big number, so we should write a program to do it! We certainly don't want to do the exponentiation and multiplication every time we use the operation in our program, and that's where functions come in! Functions can take in parameters (<math>a</math> and <math>b</math>) and return a result depending on the parameters. | We know this will be a big number, so we should write a program to do it! We certainly don't want to do the exponentiation and multiplication every time we use the operation in our program, and that's where functions come in! Functions can take in parameters (<math>a</math> and <math>b</math>) and return a result depending on the parameters. | ||

| − | + | def up_down_arrow(a,b): | |

| − | + | return ((a**b) * (b**a)) | |

| − | |||

| − | def up_down_arrow(a,b): | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Above is the code to define our function. We need to print the final result at the end, so we must put a print statement at the end. | Above is the code to define our function. We need to print the final result at the end, so we must put a print statement at the end. | ||

| − | + | def up_down_arrow(a,b): | |

| − | + | return ((a**b) * (b**a)) | |

| − | + | print(up_down_arrow(up_down_arrow(2,up_down_arrow(1,2)),2) | |

| − | def up_down_arrow(a,b): | ||

| − | |||

| − | print(up_down_arrow(up_down_arrow(2,up_down_arrow(1,2)),2) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

All those nested up_down_arrow's might be confusing at first, but it really isn't that confusing. | All those nested up_down_arrow's might be confusing at first, but it really isn't that confusing. | ||

| Line 153: | Line 205: | ||

We will keep our up_down_arrow function because in the definition of our all_around function we will use it. Then, we will define the all_around function. | We will keep our up_down_arrow function because in the definition of our all_around function we will use it. Then, we will define the all_around function. | ||

| + | def up_down_arrow(a,b): | ||

| + | return ((a**b) * (b**a)) | ||

| + | def all_around(a,b): | ||

| + | return ((a * b * up_down_arrow(a,b)) ** 2) | ||

| − | + | We must print all_around(87,132) at the end. Once we do that, and we run our program, we get a super huge number that has over 800 digits! | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | We must print all_around(87,132) at the end. Once we do that, and we run our program, we get a | ||

===Understanding Functions=== | ===Understanding Functions=== | ||

| Line 175: | Line 222: | ||

How will the function know what number to add 1 to? We will input a '''parameter''' for the function to add 1 to. | How will the function know what number to add 1 to? We will input a '''parameter''' for the function to add 1 to. | ||

| + | def add_one(x): | ||

| + | return x + 1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this function, <math>x</math> is the parameter. | ||

| + | |||

| + | def add_one(x): | ||

| + | return x + 1 | ||

| + | print(add_one(2)) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the print statement, we set <math>x</math> as 2, and the function returns <math>2 + 1 = 3,</math> so the program prints <math>3</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Simple Program Example 2==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Define a function that prints out an input.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We will use a parameter again. | ||

| + | |||

| + | def print_function(x): | ||

| + | print(x) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Uh oh! We have nothing to return! Therefore, we will return nothing (or null), by just writing return. | ||

| + | |||

| + | def print_function(x): | ||

| + | print(x) | ||

| + | return | ||

| + | print_function("print_function") | ||

| + | |||

| + | This code prints out print_function. print_function() is said to be '''called''' in the final line of the code. Again, we set <math>x</math>, our parameter, as "print_function." | ||

| + | == Classes == | ||

| + | Classes are objects that can be "called" on to initialize objects! For example, you can define a <code>Dog</code> class, and when you call <code>Dog(...)</code> it will return a Dog object. Dog here is a data type, similar to stuff like str, int, etc. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Note: Classes are, in my opinion, one of the harder-to-understand parts of Python. The rest of this page does not really talk about classes, so you ''might'' want to skip this and come back to it later.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Defining a Class=== | ||

| + | We can define a class by doing the following: | ||

| + | class Example: | ||

| + | # stuff instead of pass goes here normally | ||

| + | pass | ||

| + | Usually, classes use CamelCase convention for capitalization. | ||

| + | We can "call" a class by doing the following: | ||

| + | Example() | ||

| + | which returns an instance of the class. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Setting Attributes=== | ||

| + | We can set attributes, which are the data an instance stores, like this: | ||

| + | e = Example() # get an example object | ||

| + | e.aaa = "aaa" | ||

| + | print(e.aaa) | ||

| + | You can also declare the attributes of a class in advance in the definiton: | ||

| + | class Example: | ||

| + | aaa = str | ||

| + | bbb = int | ||

| + | Note that those types that are specified are just for the programmer to read; they might not be enforced by the interpreter. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Methods=== | ||

| + | Methods are functions that apply to a class. You can define a method like below. In methods, you use <code>self.attributeName</code> to reference attributes: | ||

| + | class Dog: | ||

| + | name = str | ||

| + | def hello(self): # self is always required as the first parameter | ||

| + | print("Hello from a dog, ",self.name,"!",sep='') | ||

| + | and you can do stuff on it: | ||

| + | # create a dog object | ||

| + | d = Dog() | ||

| + | d.name = "helloDog" # set its name | ||

| + | # say hello from the Dog | ||

| + | d.hello() # note you omit the self parameter here. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===__init__=== | ||

| + | __init__ is where one should initialize class-wide variables; it is called when you "call" a class, like <code>Example()</code>. Even though you cannot directly do it, think of "calling" a class as <code>Example.__init__()</code>. For example: | ||

| + | class Person: | ||

| + | def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,age): | ||

| + | self.name=first_name+" "+last_name | ||

| + | self.age=age | ||

| + | Now I could use this class like this: | ||

| + | Person("Richard", "Rusczyk", 49) | ||

| + | Note, as described in the Methods section, self is also required in __init__ but omitted from the actual statement that calls it. Also note that the convention is to not declare attributes set in __init__ as shown in the Attributes section. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===__str__=== | ||

| + | __str__ changes the way a class appears in "print". | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let's say you want to print the python object we created: | ||

| + | p = Person("Richard", "Rusczyk", 49) | ||

| + | print(p) | ||

| + | but this is what we get: | ||

| + | <__main__.Person object at 0x7c24cb28b110> | ||

| + | (you might get different numbers; the string of numbers in hexadecimal at the end is the memory location of the object). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now, imagine being able to print the actual info of the person. Luckily, there's a way! You just need to define __str__ in your class. The class declaration is now as follows: | ||

| + | class Person: | ||

| + | def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,age): | ||

| + | self.name=first_name+" "+last_name | ||

| + | self.age=age | ||

| + | def __str__(self): | ||

| + | return self.name+', '+str(self.age)+' years old' | ||

| + | Now, when we do | ||

| + | p = Person("Richard", "Rusczyk", 49) | ||

| + | print(p) | ||

| + | we will get what is returned by the __str__ function, which is | ||

| + | Richard Rusczyk, 49 years old | ||

| + | in this case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Overloading=== | ||

| + | Overloading means changing a function of a parent class you are inheriting to do what you want it to do. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =="Soft Coding" Programs== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the next few examples, you will see why hard coding programs is bad. Hard coding programs refers to coding a program that is hard to modify. For example: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 1=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Print all two digit positive integers <math>\boldsymbol{x}</math> such that <math>\boldsymbol{5x}</math> is a three digit positive integer.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can keep our code and modify some parts of it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | def check(a, min, max): | ||

| + | if a*5 > min - 1 and a*5 < max + 1: | ||

| + | return True | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | return False | ||

| + | |||

| + | def print_check(range_min, range_max, check_min, check_max): | ||

| + | for i in range(range_min, range_max + 1): | ||

| + | if check(i, check_min, check_max): | ||

| + | print(i) | ||

| + | return | ||

| + | |||

| + | print_check(10, 99, 100, 999) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Why did we add so many functions? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Well, if the numbers in a problem change (and the words stay the same), and you need to change a lot of numbers in your program, your program is considered '''hard-coded'''. We want our programs to be as '''soft-coded''' as possible. In our new program, we only need to change 4 numbers (in the print_check() statement) if the numbers in the problem change. Therefore, our program is relatively soft-coded. There are still ways to soft-code this program even more, though. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If we run our program, we get our answer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All numbers from 20 to 99 work! | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 2=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Print all three digit positive integers <math>\boldsymbol{x}</math> such that <math>\boldsymbol{5x}</math> is a three digit positive integer.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can just change the print_check line at the end to | ||

| + | |||

| + | print_check(100, 999, 100, 999) | ||

| + | |||

| + | and our program will be ready to be run. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All numbers from 100 to 199 work. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 3=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Print all two digit positive integers <math>\boldsymbol x</math> such that <math>\boldsymbol{3x}</math> is a three digit positive integer.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Uh oh. Only changing the print_check line won't work. We will need to change our functions! | ||

| + | |||

| + | def check(a, min, max, factor): | ||

| + | if a*factor > min - 1 and a*factor < max + 1: | ||

| + | return True | ||

| + | else: | ||

| + | return False | ||

| + | |||

| + | def print_check(range_min, range_max, check_min, check_max, check_factor): | ||

| + | for i in range(range_min, range_max + 1): | ||

| + | if check(i, check_min, check_max, check_factor): | ||

| + | print(i) | ||

| + | return | ||

| + | |||

| + | print_check(10, 99, 100, 999, 3) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this step, we added a parameter in both functions. We also soft-coded our program even more! Hooray! | ||

| + | |||

| + | All integers from 34 to 99 work. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 4=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Print all two digit positive integers <math>\boldsymbol x</math> such that <math>\boldsymbol{12x}</math> is a positive integer from 500 to 900.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | This problem may look a bit different from the other ones, but it really is the same thing, except that the factor is 12 and check_min and check_max are 500 and 900, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once we change the final print_check() line to satisfy our needs, we can run our program. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All numbers from 42 to 75 work! | ||

| + | |||

| + | Congrats! You have written your first programs above 10 lines of code! | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Random== | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is a package in Python that allows the use of random numbers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 1=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Generate a random number from 1 to 6.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Easy peasy. We will just generate a random number from 1 to 6 with the package like this: | ||

| + | |||

| + | import random | ||

| + | print(random.randint(1,6)) | ||

| + | |||

| + | As you can see, when you run this program, you get a random integer from 1 to 6. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 2=== | ||

| − | + | '''Simulate the rolling of 1000 dice. Now, count the number of times you roll 6. Print that number out.''' | |

| − | + | We can create a function that returns a random number from 1 to 6. Then, we can make a for loop that rolls the dice 1000 times and check if it is a 6. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | import random | ||

| + | count = 0 | ||

| + | |||

| + | def roll(): | ||

| + | return random.randint(1,6) | ||

| + | |||

| + | for i in range(1, 1001): | ||

| + | if roll() == 6: | ||

| + | count += 1 | ||

| − | + | print(count) | |

| + | |||

| + | If we run this, we will get a number around 170. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Program Example 3=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Simulate the rolling of 10,000 dice. Now, count the amount of times you roll 3. Print that amount out.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can keep our roll function and our code inside the for loop, but we need to change our for loop statement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can actually soft-code our program more. Let's turn the whole for loop into a function! | ||

| + | |||

| + | import random | ||

| + | |||

| + | def roll(): | ||

| + | return random.randint(1,6) | ||

| + | |||

| + | def count(amount): | ||

| + | count_ = 0 | ||

| + | |||

| + | for i in range(1, amount+1): | ||

| + | if roll() == 3: | ||

| + | count_ += 1 | ||

| + | return count_ | ||

| + | |||

| + | print(count(10000)) | ||

| + | |||

| + | If we run this code, it works. | ||

| + | ===Program Example 4=== | ||

| − | < | + | '''One of my friends loves rolling dice. He is going to roll 1 die tomorrow, 2 dice two days from now, 3 dice three days from now, and so on so that he rolls <math>\boldsymbol a</math> dice <math>\boldsymbol a</math> days from now. He gets tired rolling dice after rolling dice for 365 days (so the last day he rolls 365 dice). In Python, simulate this. How many times does he roll 3 after 365 days of rolling dice?''' |

| − | + | We can use a for loop that calls a function multiple times. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | import random | ||

| + | |||

| + | def roll(): | ||

| + | return random.randint(1,6) | ||

| + | |||

| + | def count(amount): | ||

| + | count_ = 0 | ||

| + | for i in range(1, amount+1): | ||

| + | if roll() == 3: | ||

| + | count_ += 1 | ||

| + | return count_ | ||

| + | |||

| + | total = 0 | ||

| + | |||

| + | for i in range(1, 366): | ||

| + | total += count(i) | ||

| + | |||

| + | print(total) | ||

| − | + | This is a really long program, but the whole program should make sense if you look at it for a while. We defined our count function in the previous example, and now we are using it with a for loop and a running total. | |

| − | + | You should get a number around 11,000 when you run it. Wow, lots of 3's! | |

| − | + | ===Program Example 5=== | |

| − | + | '''20 of my friends love rolling dice. They are all going to roll 1 die each tomorrow, 2 dice each two days from now, 3 dice each three days from now, and so on so that they roll <math>\boldsymbol a</math> dice each <math>\boldsymbol a</math> days from now. But, one of my friends gets tired very quickly and he only rolls dice for 1 day and stops. Another friend only will roll dice for 2 days, and another will roll dice for three days only, and so on up to the fact that my last friend will roll dice for 20 days. In Python, simulate this. How many times does someone roll 3 after everything?''' | |

| + | We will have to make our for loop into a function again. | ||

| − | + | import random | |

| + | |||

| + | def roll(): | ||

| + | return random.randint(1,6) | ||

| + | |||

| + | def count(amount): | ||

| + | count_ = 0 | ||

| + | for i in range(1, amount+1): | ||

| + | if roll() == 3: | ||

| + | count_ += 1 | ||

| + | return count_ | ||

| + | |||

| + | def count2(amount): | ||

| + | total = 0 | ||

| + | for i in range(1, amount + 1): | ||

| + | total += count(i) | ||

| + | return total | ||

| + | |||

| + | def count3(amount): | ||

| + | total = 0 | ||

| + | for i in range(1, amount + 1): | ||

| + | total += count2(i) | ||

| + | return total | ||

| + | |||

| + | print(count3(20)) | ||

| − | + | (Our program is so long!) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | I also made a new function just in case we needed to turn that into a function later. | ||

| − | + | '''Make sure''' you read the code carefully and you fully understand it. If you don't understand every single line of code, then you will get confused later on in this article. | |

| + | When you run this program, you might be surprised that the answer isn't so big. | ||

| − | + | ===Program Example 6=== | |

| − | + | '''365 of my friends love rolling dice. They are all going to roll 1 die each tomorrow, 2 dice each two days from now, 3 dice each three days from now, and so on so that they roll <math>\boldsymbol a</math> dice each <math>\boldsymbol a</math> days from now. But, one of my friends gets tired very quickly and he only rolls dice for 1 day and stops. Another friend only will roll dice for 2 days, and another will roll dice for three days only, and so on up to the fact that my last friend will roll dice for 365 days. In Python, simulate this. How many times does someone roll 3 after everything?''' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | + | Because we soft-coded our program so much, all we have to do is change the last line so the parameter of count3() is 365. | |

| − | + | If we run it...we get a big answer, as expected. It also takes quite a while! | |

| − | + | You may not have realized that we soft-coded our program at all, but the whole point of functions is to soft-code programs! | |

| − | + | Congrats on writing a program that is around 25 lines long! | |

| − | + | ==Very Basic Datatypes== | |

| − | + | An integer is a basic datatype in Python. Basically, all variables with the datatype of '''int''' is an integer. | |

| − | + | A string is another basic datatype, and it is a string of characters enclosed by quotes. | |

| − | + | ===Why Are Datatypes So Important?=== | |

| − | + | Let's say we wanted to make a program that would add 2 and 3. Some bogus code would be: | |

| + | x="2" | ||

| + | y="3" | ||

| + | print(x+y) | ||

| − | + | If you ran this code, you would get 23. Why is that? | |

| − | + | Well, here, x and y are strings. When you perform the addition operator to strings in Python, it concatenates the strings, giving 23. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The real code is: | ||

| − | + | x=2 | |

| + | y=3 | ||

| + | print(x+y) | ||

| − | + | If you run this, you will get <math>5</math>, which is correct. | |

| + | Here's another reason datatypes are important. Now, we will introduce the datatype called the '''floating point number''', or '''float'''. A floating-point number is a number with a decimal point. | ||

| − | + | Let's go back to the IDLE. Type "0.1*10". The result is 1.0. Notice the decimal point. | |

| − | + | Let's type something different. Type <code>0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1</code>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </code> | ||

| + | '''WHAT!?''' | ||

| − | + | You would have expected the answer to be 1, but it isn't 1. What happened? | |

| − | + | '''Float approximation''' happened. Most (almost all) programming languages have a bad float approximation. That means that 1.0 can turn into 0.99999999999999 and 0.5 can turn into 0.49999999999999999993. That only happens with floats, so we should try to use floats as sparingly as possible. | |

| − | == | + | ==Lists== |

| − | ''' | + | A for loop iterates over a '''list'''. A list is a bunch of objects stored in one variable. (Hey! A list is a datatype!) For loops are highly related to lists. |

| − | + | Let's say we wanted to make a program to print all the items in a list. | |

| − | We will | + | We will first create the list, using the code: |

| + | myList = [1,4,6,8] | ||

| − | + | This is a list with four items: 1, 4, 6, and 8. | |

| − | + | We must now print all elements of it with a for loop: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | myList = [1,4,6,8] | ||

| + | for i in myList: | ||

| + | print(i) | ||

| − | + | When we run this program, we get the numbers 1, 4, 6, and 8, as expected. | |

| − | + | ===Accessing Values=== | |

| + | Let's say we wanted to print out the second item in a list. We will use '''indexes'''. | ||

| − | < | + | The index of the first item in a list is always 0. The index of the second is 1. The index of the <math>n</math>th is <math>n-1.</math> |

| − | + | To print out the second item, we will use an index of 1, like this: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | myList = [1,4,6,8] | ||

| + | print(myList[1]) | ||

| − | + | Notice that the index is inside of the square brackets. | |

| − | + | ===Adding Values=== | |

| − | + | We can use the list.append() function to add an object to the end of a list. | |

| − | + | myList.append(10) | |

| − | + | will add 10 to the list, which makes myList = [1,4,6,8,10]. | |

| − | === | + | ===Removing Items From Lists=== |

| − | + | We can use the list.remove() function to remove a specific item in a list. | |

| − | + | For example, consider this code. | |

| + | myList = [1,2,3] | ||

| + | myList.remove(3) | ||

| − | + | This code will make myList turn into [1,2]. The element, 3, gets removed. | |

| − | + | ===len(list)=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The len(list) function returns the length of a list. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | This code will print 3. | |

| − | |||

| + | myList = [1,2,3] | ||

| + | print(len(myList)) | ||

| − | + | The length of myList is 3, so Python prints 3. | |

| − | + | ===All Kinds Of Lists=== | |

| − | + | Lists don't have to be only integers! | |

| − | + | myList = [1,"Hi","Hello world", 3.5, 3.14159265358979323] | |

| − | + | If fact, there can be lists inside of lists! | |

| − | + | myList = [[1,2,3], [3,4,5], [5,6,"Hello world"], "BOB", 3.1415926] | |

| − | + | Even this! | |

| + | myList = [[1, [1, [1,2,3],3],3], [[[3,["Hello world", 4],5],4,5],4,5], [5,6,7,[1,[1,2,3],3],"Hello world"], "BOB", 3.1415926, True] | ||

| − | + | If you look at that list carefully, you will find lists inside of lists inside of lists inside of lists! And, a boolean at the end! | |

| − | + | Like variables, you can have as many lists in a program as you want (a list is a variable)! | |

| − | |||

| + | myList = [1,2,3,4] | ||

| + | yourList = [5,6,7,8] | ||

| + | hisList = [9,10,11,12] | ||

| + | herList = [13,14,15,16] | ||

| + | theirList = [17,18,19,20] | ||

| + | ourList = [21,22,23,24] | ||

| + | listsOfLists = [[1,2,3,4],[5,6,7,8],[9,10,11,12],[13,14,15,16],[17,18,19,20],[21,22,23,24]] | ||

| − | and our | + | ===Splitting Lists=== |

| + | Split Operator Basics: | ||

| + | genericList[where to start:where to end:what size steps to take] | ||

| + | The value where to start is inclusive, and denotes the index where your split list begins. It has a default value of 0. | ||

| + | The value where to end is exclusive, and denotes the index where your split list ends. It has a default value of len(genericList). | ||

| + | The value what size steps denotes the size of the steps your split takes(more on that later). It has a default value of 1. | ||

| + | Say you want to split a list and only return certain indices, for example if you wanted to split a list called data and put the first two elements into a list called head and the last two into a list called tail, you would split like this: | ||

| + | data = [1, 3, 4, 23.5, 40, 55] | ||

| + | head = data[:2] | ||

| + | tail = data[-2:] # negative list indices represent the end of a list, so -1 is the last element and -2 is the second-to-last | ||

| + | Step Size: | ||

| + | We will practice writing a few functions that select every other element and will reverse in a list using step size. | ||

| + | A step size of two means skip every other list index, so we can write our first function. | ||

| + | def selectEveryOtherElement(list): | ||

| + | return list[::2] | ||

| + | But which step size will get us our desired reversed list? We could start at the end of the list and iterate backwards, but how would we do that? | ||

| + | Negative Step Size: | ||

| + | A step size that is negative means skip a certain amount of elements, but backwards. If we were to start at 0, with a step size of -1, we would be able to iterate backwards over the list! | ||

| + | def reverse(list): | ||

| + | return list[::-1] | ||

| + | Splitting lists with ratios: | ||

| + | What if we wanted to be able to split a list based upon a ratio. For example, the common 80:20 train to test ratio in machine learning? Here is how you would do it: | ||

| + | def eighty-twenty(list): | ||

| + | train = list[:int(len(list) * (4 / 5))] # We must include the int() method to convert to an integer if len(list) % 5 != 0 | ||

| + | test = list[int(len(list) * 4 / 5)] | ||

| + | return [train, test] # We then return a list with the train and test lists inside | ||

| − | + | ===List Comprehension=== | |

| + | List Comprehension is a shorthand way to initialize an array. Let's say that you want to remove duplicate values from an array. | ||

| + | arr = [3, 4, 3, 5, 1, 5, 9] | ||

| + | new_arr = [] | ||

| + | new_arr = [x for x in arr if x not in new_arr] # this loops through each value in arr, and checks if it is already in new_arr | ||

| − | == | + | ==Tuples== |

| + | Tuples are an immutable alternative to lists! You can create them similar to lists, but instead with parentheses instead of brackets! | ||

| − | + | Immutable means unable to be changed. | |

| − | + | ===Initialization=== | |

| + | my_tuple = (1, 2) # can be any size you want! | ||

| + | print(my_tuple[0]) # returns 1 | ||

| + | print(len(my_tuple)) # returns 2 | ||

| + | my_tuple[0] = 2 # WRONGO: you cannot do item assignment on tuples, similar to how you cannot on strings! This is because of their immutable aspect! To do so, you must create a new tuple and reasign my_tuple! | ||

| + | ===But Why? (IMPORTANT NOTE)=== | ||

| + | Tuples are useful because the keys and items of dictionaries and sets (respectively) must be immutable (thus hashable). This is why numbers, strings, and tuples (all immutable) can be used as dictionary keys whereas lists cannot! | ||

| − | + | In addition, tuples take up less memory. Lists often pre-allocate a bunch of memory because allocating memory is slow, and a list often needs to be appended to. | |

| − | + | ===Lists Inside Tuples=== | |

| − | + | my_tuple=([1,2],2) | |

| − | + | my_tuple[0][1]=1 | |

| − | + | print(my_tuple) | |

| − | + | This outputs ([1, 1], 2). But why can be a tuple changed in this case? | |

| − | + | That's because we have a list inside. In Python, what's inside the tuple a reference to the list instead of the actual list contents. So when you access my_tuple[0] it is giving you the reference to the list, which is actually change-able. That is why you can change a list inside a tuple. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | However, tuples which contains mutable items are not hashable. For example, if we run | |

| − | < | + | a = {my_tuple:1, 1:2} |

| + | after the above code box, this is what we get: | ||

| + | Traceback (most recent call last): | ||

| + | File "<main.py>", line 4, in <module> | ||

| + | TypeError: unhashable type: 'list' | ||

| + | ==Dictionaries (Hash Maps)== | ||

| − | + | A dictionary (a type of datatype) is a bunch of keys and values. There is a major difference between dictionaries and lists. Lists are ordered; dictionaries are not. | |

| − | + | Here is the '''syntax''' of creating a dictionary: | |

| − | = | + | myDictionary = {1:"one",2:"two"} |

| − | + | This dictionary has two key/value pairs. Notice it is surrounded in curly braces. The keys are 1 and 2; the values are "one" and "two." | |

| − | + | How is this useful? Let's make a simple program to test it out. | |

| − | + | myDictionary = {1:"one",2:"two"} | |

| + | print(myDictionary[1]) | ||

| + | print(myDictionary[2]) | ||

| − | + | ===Accessing Values=== | |

| − | + | To access a value in a dictionary, you put in the key. | |

| − | + | myDictionary[1] | |

| − | + | returns one, because 1 is the key to "one." | |

| − | === | + | ===Adding New Values=== |

| − | + | To overwrite a value, we do this. | |

| − | + | myDictionary[1] = "won" | |

| + | The value to the key 1 is now "won." | ||

| − | + | To add a value, we do the same thing! | |

| − | + | myDictionary[3] = "three" | |

| − | + | This adds a key 3 with a value of "three." | |

| − | |||

| + | ==Sets (Hash Sets)== | ||

| − | + | Sets in python are quite similar to those in mathematics! A set cannot contain duplicate values and may only contain immutable objects (strings, tuples, but not lists!) Just like dictionaries, lookups for items are \(\mathcal O(1)\), and insertions are as well! | |

| − | = | + | my_set = set() |

| + | my_set.add(1) | ||

| + | print("Is 1 in the set?", 1 in my_set) | ||

| + | print("Size of set", len(my_set)) | ||

| + | my_set.add(1) | ||

| + | print("Size of set", len(my_set)) # still equals 1! make sure you see why! | ||

| − | + | Note: \(\mathcal O(1)\) means a constant time complexity. It means in this context that whatever size the set and/or other parameters are, the time is approximately constant. | |

| − | + | ==Misc Concepts== | |

| + | This section will talk about some concepts that we haven't learned yet. | ||

| − | + | ====Concatenating Strings==== | |

| − | + | Concatenating strings is putting them together. For example, "one" concatenated with "two" gives "onetwo." You use the + operator, just like numbers, to concatenate strings. | |

| − | + | In case the previous sentence causes confusion, note: "1"+"2" is "12" not "3". | |

| − | + | The following string, | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | "Hello, " + person2 + "! How are you?" | ||

| − | If | + | depends on what person2 was. If person2 was Bob, the string would be: |

| − | + | "Hello, Bob! How are you?" | |

| − | + | It fits together perfectly! | |

| − | + | You cannot concatenate strings with integers. For example, doing this: | |

| − | + | "2" + 3 | |

| + | will not work. Instead, to get an answer of "23", you must do this: | ||

| − | + | "2" + str(3) | |

| − | + | That turns 3 into a string so it is "3", and the result will be "23". | |

| + | ====Formatting Strings==== | ||

| + | There is a faster way to do the stuff in the above section: | ||

| + | name="aops" | ||

| + | "hello %s" % name | ||

| − | + | or even faster | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | wiki_name="AOPS WIKI" | ||

| + | "This is the {0}".format(wiki_name) | ||

| − | + | Later versions might support f-strings: | |

| − | = | + | method="apple method" |

| + | f"Use the {method}!" | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | This is useful in cases like this: | |

| + | answer = 10 # in reality this will be computed | ||

| + | print(f"The answer is {answer}") | ||

| + | It can make the code a lot more elegant. Without this we have to say | ||

| + | print("The answer is", answer) | ||

| + | While it might seem redundant right now, if you have to deal with formatting in output, than format or f-strings are a perfect option. | ||

| − | + | ====Line Breaks==== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | We can use multiple line breaks to make our code more organized. There are some places that you cannot line break. For example, this code will produce an error: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | myList = | |

| − | + | [1,2,3] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | This code does not work. | |

| − | + | This code '''does work''': | |

| − | |||

| − | + | myList = [ | |

| − | + | 1,2,3] | |

| + | It is accepted when you break a line right after the [. It is also accepted right after a comma. (And right before the ending ].) | ||

| − | + | myList = [ | |

| + | 1, | ||

| + | 2, | ||

| + | 3 | ||

| + | ] | ||

| − | + | ==Challenge Program== | |

| − | + | In this section, we will attempt the hardest program so far in this article. | |

| − | ''' | + | '''Make a conversation generator that will generate random conversations between different people.''' |

| − | We | + | First, we will generate the people. We can use a list and generate two random numbers. |

| + | import random | ||

| + | |||

| + | peopleNames = [ | ||

| + | "Bob", | ||

| + | "Kyle", | ||

| + | "James", | ||

| + | "Richard", | ||

| + | "Zachary", | ||

| + | "Olivia", | ||

| + | "Jonathan", | ||

| + | "Will", | ||

| + | "Bobby", | ||

| + | "Kevin" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | person1 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | peopleNames.remove(person1) | ||

| + | person2 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| − | + | (I made it more organized by separating the long lines of code into multiple lines. It only works when you have a line break right after each item in the list.) | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Here, we use the remove() function to remove person1 from the list to make sure we don't use the same name twice. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | We also used the len() function to find the length of the list (soft-coding!) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Now, we need to create a list of possible values for the first thing that person1 says (person1 will always be the first one to talk). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Then, we will print it out. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | print( | + | import random |

| − | + | ||

| + | peopleNames = [ | ||

| + | "Bob", | ||

| + | "Kyle", | ||

| + | "James", | ||

| + | "Richard", | ||

| + | "Zachary", | ||

| + | "Olivia", | ||

| + | "Jonathan", | ||

| + | "Will", | ||

| + | "Bobby", | ||

| + | "Kevin" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | person1 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | peopleNames.remove(person1) | ||

| + | person2 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | |||

| + | first = [ | ||

| + | "Hi!", | ||

| + | "Hello!", | ||

| + | "Good morning!", | ||

| + | "Hello, " + person2 + "!", | ||

| + | "Hi.", | ||

| + | "Hi, " + person2 + "!" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person1 + ": " + first[random.randint(0, (len(first) - 1))]) | ||

| − | + | If we test out this program, we can confirm that this part indeed does work. This program is already getting long! Now, we will use the same method and create the second message. | |

| − | + | import random | |

| + | |||

| + | peopleNames = [ | ||

| + | "Bob", | ||

| + | "Kyle", | ||

| + | "James", | ||

| + | "Richard", | ||

| + | "Zachary", | ||

| + | "Olivia", | ||

| + | "Jonathan", | ||

| + | "Will", | ||

| + | "Bobby", | ||

| + | "Kevin" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | person1 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | peopleNames.remove(person1) | ||

| + | person2 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | |||

| + | first = [ | ||

| + | "Hi!", | ||

| + | "Hello!", | ||

| + | "Good morning!", | ||

| + | "Hello, " + person2 + "!", | ||

| + | "Hi.", | ||

| + | "Hi, " + person2 + "!" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person1 + ": " + first[random.randint(0, (len(first) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | second = [ | ||

| + | "Hi! How are you today?", | ||

| + | "Hello! How are you?", | ||

| + | "Good morning! How are you today?", | ||

| + | "Hello, " + person1 + "! How are you?", | ||

| + | "Hi. How are you?", | ||

| + | "Hi, " + person1 + "! How are you today?" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person2 + ": " + second[random.randint(0, (len(second) - 1))]) | ||

| − | + | We will repeat this for the rest of the conversation: | |

| − | === | + | import random |

| + | |||

| + | peopleNames = [ | ||

| + | "Bob", | ||

| + | "Kyle", | ||

| + | "James", | ||

| + | "Richard", | ||

| + | "Zachary", | ||

| + | "Olivia", | ||

| + | "Jonathan", | ||

| + | "Will", | ||

| + | "Bobby", | ||

| + | "Kevin" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | person1 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | peopleNames.remove(person1) | ||

| + | person2 = peopleNames[random.randint(0, (len(peopleNames) - 1))] | ||

| + | |||

| + | first = [ | ||

| + | "Hi!", | ||

| + | "Hello!", | ||

| + | "Good morning!", | ||

| + | "Hello, " + person2 + "!", | ||

| + | "Hi.", | ||

| + | "Hi, " + person2 + "!" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person1 + ": " + first[random.randint(0, (len(first) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | second = [ | ||

| + | "Hi! How are you today?", | ||

| + | "Hello! How are you?", | ||

| + | "Good morning! How are you today?", | ||

| + | "Hello, " + person1 + "! How are you?", | ||

| + | "Hi. How are you?", | ||

| + | "Hi, " + person1 + "! How are you today?" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person2 + ": " + second[random.randint(0, (len(second) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | third = [ | ||

| + | "I'm feeling awesome! And you?", | ||

| + | "I'm feeling alright! How are you?", | ||

| + | "I'm good, thank you. How are you feeling?", | ||

| + | "I'm fine!" , | ||

| + | "How are you today?" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person1 + ": " + third[random.randint(0, (len(third) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | fourth = [ | ||

| + | "I'm feeling great!", | ||

| + | "I'm awesome!", | ||

| + | "Thanks for asking! I am feeling good today!", | ||

| + | "I'm feeling awesome today! Yippee!" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person2 + ": " + fourth[random.randint(0, (len(fourth) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | fifth = [ | ||

| + | "It's so nice out today!", | ||

| + | "Today is such a cloudy day.", | ||

| + | "I hate it when it is so cloudy outside!", | ||

| + | "It's partly cloudy today!" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person1 + ": " + fifth[random.randint(0, (len(fifth) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | sixth = [ | ||

| + | "I know, right?", | ||

| + | "I know.", | ||

| + | "Yeah!", | ||

| + | "True." | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person2 + ": " + sixth[random.randint(0, (len(sixth) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | seventh = [ | ||

| + | "Sorry, I need to leave. Bye!", | ||

| + | "I gotta go. Bye!", | ||

| + | "Sorry, I don't have time to stay and chat. I've got to go somewhere. Bye!" | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person1 + ": " + seventh[random.randint(0, (len(seventh) - 1))]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | eighth = [ | ||

| + | "Bye!", | ||

| + | "Good-bye!", | ||

| + | "Bye, " + person1 + "." | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | print(person2 + ": " + eighth[random.randint(0, (len(eighth) - 1))]) | ||

| − | + | Whew! So long! | |

| − | + | Once we run our program. It works! This program really wasn't that hard. | |

| − | + | Congrats! You've made it so far! | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Now, try making this with ''functions''.'' | |

Latest revision as of 20:58, 3 October 2024

Important: It is extremely recommended that you read Getting Started With Python Programming before reading this unless you already know some programming knowledge.

(Note: This is a really long article. To learn the most from this article, you need to read everything in order and skip nothing, unless you are absolutely absolutely sure that that content is way too easy for you.)

This article will talk about some basic Python programming. If you don't even know how to install Python, look here.

Note that this article has lots of program examples. It is recommended (but not required) to try these on your own before looking at the solutions.

Contents

Booleans

Program Example

Print all two-digit positive integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a two-digit positive integer.

is a two-digit positive integer.

We can create a function with our previous code.

We will have to slightly modify our function so we can use it in a for loop at the end:

def check(x):

if x*5 > 9 and x*5 < 100:

return True

else:

return False

True and False are what are called booleans. When an if or elif statement receives True, the code inside of the statement happens. When an if or elif statement receives False, the code inside of the statement does not happen.

We must create a for loop that will iterate through all two digit positive integers.

def check(x):

if x*5 > 9 and x*5 < 100:

return True

else:

return False

for i in range(10,100):

if check(i):

print(i)

The final for loop checks if ![]() is a two digit integer. If it is, the function returns True and the code inside the if statement gets run. If it isn't, the function returns False and the code inside the if statement gets ignored.

is a two digit integer. If it is, the function returns True and the code inside the if statement gets run. If it isn't, the function returns False and the code inside the if statement gets ignored.

If we run this, we will get the answer.

All two digit integers from 10 to 19 inclusive work!

Flow

Flow consists of if statements, elif (else if) statements, and else statements.

- An if statement checks if a comparison is true.

- An else statement checks if a comparison is not true. It is used after an if statement (and all elif statements after the if statement) and it shares the same comparison as the if statement.

- An elif statement checks for two things: if a comparison is true, and if a comparison is not true. It is used right after the if statement.

Program Example

if you multiply 10 by 5, do you get a two digit number?

This problem is super easy to solve without a program, but let's write a program to solve this anyway. We will use an if statement to check if ![]() is less than 100 and greater than 9.

is less than 100 and greater than 9.

if 10*5 > 9:

if 10*5 < 100:

print("Yes")

else:

print("No")

else:

print("No")

This code means, if 10*5 > 9, then we will check if it is less than 100. If it is not greater than 9, however, we will print No. If it is greater than 9, we check if it is less than 100. If it is, we print Yes. If it isn't we print No.

These nested if statements can be very confusing. Luckily, there is a faster an easier way to do this.

if 10*5 > 9 and 10*5 < 100:

print("Yes")

else:

print("No")

This code checks for the two conditions at the same time. If we run it, we get our answer of Yes.

Always remember; the simpler your code is the better it will preform!

Loops

There are two different kinds of loops in Python: the for loop and the while loop.

The For Loop

The for loop iterates over a list, or an array, of objects. You have probably seen this code before:

This for loop iterates over the list of integers from 1 to 51, but excludes 51. This is because python will always think of the last number as a barrier and the number before as the stopping point; Python will count the 1st number though as it is the starting point. That means it is a list from 1 to 50, inclusive. On every iteration, Python will print the number that the loop is iterating through.

For example, in the first iteration, i = 1, so Python prints 1.

In the second iteration, i = 2, so Python prints 2.

This continues so on until the number, 50, is reached. Therefore, the last number Python will print out is 50.

We call the range function a generator because it returns a list (find out more in the later section!). When we do

for i in something

the something is an iterable object (string, list, tuple, so on). The variable i is just an item!

Program Example

Find

To do this task, we must create a for loop and loop over the integers from 1 to 50 inclusive:

for i in range(1,51):

Now what? We must keep a running total and increase it by ![]() every time:

every time:

total = 0

for i in range(1,51):

total += 2**i

We must not forget to print the total at the end!

total = 0

for i in range(1,51):

total += 2**i

print(total)

You must exit out of the for loop one you reach the print(total) line by pressing backspace.

Once you run your program, you should get an answer of ![]()

The While Loop

While loops don't loop over a list. They loop over and over and over...until...a condition becomes false.

i = 10

total = 0

while i < 1000:

total += i

i += 10

print(total)

In this code, the while loop loops 100 times, until ![]() becomes greater than or equal to 1000.

becomes greater than or equal to 1000.

Program Example

Find  using a while loop.

using a while loop.

We must create a while loop that will iterate until n is greater than ![]()

n = 1

total = 0

while n <= 50:

total += 2**n

n += 1

print(total)

We must not forget to include the n += 1 line at the end of the while loop!

If we run this, we will get the same answer as last time, ![]()

Notes/key

-just for any one who forgot, <= means less than or equal

-The double ** means "too the power of" as in 5**2 = 25, in this program (it can have other meanings with different key phrases)

- += This operator means increment. For example 2 += 5 gives seven. This is one of the assigment operators[1]

(To anyone who is annoyed that I'm writing these notes, I'm sorry and all, but this text book does not seem to have much basic explanation, so I'm adding some.)

Functions

In this section, we will define new operations and do arithmetic with them in Python.

The New Operation

Let's say that you defined a new binary operation, the ![]() You want it to be so

You want it to be so ![]() Therefore,

Therefore, ![]() and

and ![]() Let's call this operation an up down arrow.

Let's call this operation an up down arrow.

Program Example 1

Find ![]()

We know this will be a big number, so we should write a program to do it! We certainly don't want to do the exponentiation and multiplication every time we use the operation in our program, and that's where functions come in! Functions can take in parameters (![]() and

and ![]() ) and return a result depending on the parameters.

) and return a result depending on the parameters.

def up_down_arrow(a,b):

return ((a**b) * (b**a))

Above is the code to define our function. We need to print the final result at the end, so we must put a print statement at the end.

def up_down_arrow(a,b):

return ((a**b) * (b**a))

print(up_down_arrow(up_down_arrow(2,up_down_arrow(1,2)),2)

All those nested up_down_arrow's might be confusing at first, but it really isn't that confusing.

If you run your program, you should get your answer: ![]()

You might be surprised that the answer is so big. If you actually start calculating the real answer without a program, you will really quickly find that the final result is ![]() which does turn out to be 16,777,216 if you use a calculator.

which does turn out to be 16,777,216 if you use a calculator.

Let's make another operation!

We will define the operation ![]() to be called all around.

to be called all around. ![]() That's an operation that will make really big numbers!

That's an operation that will make really big numbers!

Program Example 2

Find 87 all around 132.

The answer is bound to be a huge number, so we must make a program to solve it.

We will keep our up_down_arrow function because in the definition of our all_around function we will use it. Then, we will define the all_around function.

def up_down_arrow(a,b):

return ((a**b) * (b**a))

def all_around(a,b):

return ((a * b * up_down_arrow(a,b)) ** 2)

We must print all_around(87,132) at the end. Once we do that, and we run our program, we get a super huge number that has over 800 digits!

Understanding Functions

Every single function has a return value. If a function does not return anything, the return value is null. Null is a term used in programming as a placeholder that stands for nothing.

Simple Program Example 1

Define a function that adds 1 to an input.

How will the function know what number to add 1 to? We will input a parameter for the function to add 1 to.

def add_one(x):

return x + 1

In this function, ![]() is the parameter.

is the parameter.

def add_one(x):

return x + 1

print(add_one(2))

In the print statement, we set ![]() as 2, and the function returns

as 2, and the function returns ![]() so the program prints

so the program prints ![]() .

.

Simple Program Example 2

Define a function that prints out an input.

We will use a parameter again.

def print_function(x):

print(x)

Uh oh! We have nothing to return! Therefore, we will return nothing (or null), by just writing return.

def print_function(x):

print(x)

return

print_function("print_function")

This code prints out print_function. print_function() is said to be called in the final line of the code. Again, we set ![]() , our parameter, as "print_function."

, our parameter, as "print_function."

Classes

Classes are objects that can be "called" on to initialize objects! For example, you can define a Dog class, and when you call Dog(...) it will return a Dog object. Dog here is a data type, similar to stuff like str, int, etc.

Note: Classes are, in my opinion, one of the harder-to-understand parts of Python. The rest of this page does not really talk about classes, so you might want to skip this and come back to it later.

Defining a Class

We can define a class by doing the following:

class Example:

# stuff instead of pass goes here normally

pass

Usually, classes use CamelCase convention for capitalization. We can "call" a class by doing the following:

Example()

which returns an instance of the class.

Setting Attributes

We can set attributes, which are the data an instance stores, like this:

e = Example() # get an example object e.aaa = "aaa" print(e.aaa)

You can also declare the attributes of a class in advance in the definiton:

class Example:

aaa = str

bbb = int

Note that those types that are specified are just for the programmer to read; they might not be enforced by the interpreter.

Methods

Methods are functions that apply to a class. You can define a method like below. In methods, you use self.attributeName to reference attributes:

class Dog:

name = str

def hello(self): # self is always required as the first parameter

print("Hello from a dog, ",self.name,"!",sep=)

and you can do stuff on it:

# create a dog object d = Dog() d.name = "helloDog" # set its name # say hello from the Dog d.hello() # note you omit the self parameter here.

__init__

__init__ is where one should initialize class-wide variables; it is called when you "call" a class, like Example(). Even though you cannot directly do it, think of "calling" a class as Example.__init__(). For example:

class Person:

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,age):

self.name=first_name+" "+last_name

self.age=age

Now I could use this class like this:

Person("Richard", "Rusczyk", 49)

Note, as described in the Methods section, self is also required in __init__ but omitted from the actual statement that calls it. Also note that the convention is to not declare attributes set in __init__ as shown in the Attributes section.

__str__

__str__ changes the way a class appears in "print".

Let's say you want to print the python object we created:

p = Person("Richard", "Rusczyk", 49)

print(p)

but this is what we get:

<__main__.Person object at 0x7c24cb28b110>

(you might get different numbers; the string of numbers in hexadecimal at the end is the memory location of the object).

Now, imagine being able to print the actual info of the person. Luckily, there's a way! You just need to define __str__ in your class. The class declaration is now as follows:

class Person:

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,age):

self.name=first_name+" "+last_name

self.age=age

def __str__(self):

return self.name+', '+str(self.age)+' years old'

Now, when we do

p = Person("Richard", "Rusczyk", 49)

print(p)

we will get what is returned by the __str__ function, which is

Richard Rusczyk, 49 years old

in this case.

Overloading

Overloading means changing a function of a parent class you are inheriting to do what you want it to do.

"Soft Coding" Programs

In the next few examples, you will see why hard coding programs is bad. Hard coding programs refers to coding a program that is hard to modify. For example:

Program Example 1

Print all two digit positive integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a three digit positive integer.

is a three digit positive integer.

We can keep our code and modify some parts of it.

def check(a, min, max):

if a*5 > min - 1 and a*5 < max + 1:

return True

else:

return False

def print_check(range_min, range_max, check_min, check_max):

for i in range(range_min, range_max + 1):

if check(i, check_min, check_max):

print(i)

return

print_check(10, 99, 100, 999)

Why did we add so many functions?

Well, if the numbers in a problem change (and the words stay the same), and you need to change a lot of numbers in your program, your program is considered hard-coded. We want our programs to be as soft-coded as possible. In our new program, we only need to change 4 numbers (in the print_check() statement) if the numbers in the problem change. Therefore, our program is relatively soft-coded. There are still ways to soft-code this program even more, though.

If we run our program, we get our answer.

All numbers from 20 to 99 work!

Program Example 2

Print all three digit positive integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a three digit positive integer.

is a three digit positive integer.

We can just change the print_check line at the end to

print_check(100, 999, 100, 999)

and our program will be ready to be run.

All numbers from 100 to 199 work.

Program Example 3

Print all two digit positive integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a three digit positive integer.

is a three digit positive integer.

Uh oh. Only changing the print_check line won't work. We will need to change our functions!

def check(a, min, max, factor):

if a*factor > min - 1 and a*factor < max + 1:

return True

else:

return False

def print_check(range_min, range_max, check_min, check_max, check_factor):

for i in range(range_min, range_max + 1):

if check(i, check_min, check_max, check_factor):

print(i)

return

print_check(10, 99, 100, 999, 3)

In this step, we added a parameter in both functions. We also soft-coded our program even more! Hooray!

All integers from 34 to 99 work.

Program Example 4

Print all two digit positive integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a positive integer from 500 to 900.

is a positive integer from 500 to 900.

This problem may look a bit different from the other ones, but it really is the same thing, except that the factor is 12 and check_min and check_max are 500 and 900, respectively.

Once we change the final print_check() line to satisfy our needs, we can run our program.

All numbers from 42 to 75 work!

Congrats! You have written your first programs above 10 lines of code!

Random

There is a package in Python that allows the use of random numbers.

Program Example 1

Generate a random number from 1 to 6.

Easy peasy. We will just generate a random number from 1 to 6 with the package like this:

import random print(random.randint(1,6))

As you can see, when you run this program, you get a random integer from 1 to 6.

Program Example 2

Simulate the rolling of 1000 dice. Now, count the number of times you roll 6. Print that number out.

We can create a function that returns a random number from 1 to 6. Then, we can make a for loop that rolls the dice 1000 times and check if it is a 6.

import random

count = 0

def roll():

return random.randint(1,6)

for i in range(1, 1001):

if roll() == 6:

count += 1

print(count)

If we run this, we will get a number around 170.

Program Example 3

Simulate the rolling of 10,000 dice. Now, count the amount of times you roll 3. Print that amount out.

We can keep our roll function and our code inside the for loop, but we need to change our for loop statement.

We can actually soft-code our program more. Let's turn the whole for loop into a function!

import random

def roll():

return random.randint(1,6)

def count(amount):

count_ = 0

for i in range(1, amount+1):

if roll() == 3:

count_ += 1

return count_

print(count(10000))

If we run this code, it works.

Program Example 4

One of my friends loves rolling dice. He is going to roll 1 die tomorrow, 2 dice two days from now, 3 dice three days from now, and so on so that he rolls ![]() dice

dice ![]() days from now. He gets tired rolling dice after rolling dice for 365 days (so the last day he rolls 365 dice). In Python, simulate this. How many times does he roll 3 after 365 days of rolling dice?

days from now. He gets tired rolling dice after rolling dice for 365 days (so the last day he rolls 365 dice). In Python, simulate this. How many times does he roll 3 after 365 days of rolling dice?

We can use a for loop that calls a function multiple times.

import random

def roll():

return random.randint(1,6)

def count(amount):

count_ = 0

for i in range(1, amount+1):

if roll() == 3:

count_ += 1

return count_

total = 0

for i in range(1, 366):

total += count(i)

print(total)

This is a really long program, but the whole program should make sense if you look at it for a while. We defined our count function in the previous example, and now we are using it with a for loop and a running total.

You should get a number around 11,000 when you run it. Wow, lots of 3's!

Program Example 5

20 of my friends love rolling dice. They are all going to roll 1 die each tomorrow, 2 dice each two days from now, 3 dice each three days from now, and so on so that they roll ![]() dice each

dice each ![]() days from now. But, one of my friends gets tired very quickly and he only rolls dice for 1 day and stops. Another friend only will roll dice for 2 days, and another will roll dice for three days only, and so on up to the fact that my last friend will roll dice for 20 days. In Python, simulate this. How many times does someone roll 3 after everything?

days from now. But, one of my friends gets tired very quickly and he only rolls dice for 1 day and stops. Another friend only will roll dice for 2 days, and another will roll dice for three days only, and so on up to the fact that my last friend will roll dice for 20 days. In Python, simulate this. How many times does someone roll 3 after everything?

We will have to make our for loop into a function again.

import random

def roll():

return random.randint(1,6)

def count(amount):

count_ = 0

for i in range(1, amount+1):

if roll() == 3:

count_ += 1

return count_

def count2(amount):

total = 0

for i in range(1, amount + 1):

total += count(i)

return total

def count3(amount):

total = 0

for i in range(1, amount + 1):

total += count2(i)

return total

print(count3(20))

(Our program is so long!)

I also made a new function just in case we needed to turn that into a function later.

Make sure you read the code carefully and you fully understand it. If you don't understand every single line of code, then you will get confused later on in this article.

When you run this program, you might be surprised that the answer isn't so big.

Program Example 6

365 of my friends love rolling dice. They are all going to roll 1 die each tomorrow, 2 dice each two days from now, 3 dice each three days from now, and so on so that they roll ![]() dice each

dice each ![]() days from now. But, one of my friends gets tired very quickly and he only rolls dice for 1 day and stops. Another friend only will roll dice for 2 days, and another will roll dice for three days only, and so on up to the fact that my last friend will roll dice for 365 days. In Python, simulate this. How many times does someone roll 3 after everything?

days from now. But, one of my friends gets tired very quickly and he only rolls dice for 1 day and stops. Another friend only will roll dice for 2 days, and another will roll dice for three days only, and so on up to the fact that my last friend will roll dice for 365 days. In Python, simulate this. How many times does someone roll 3 after everything?

Because we soft-coded our program so much, all we have to do is change the last line so the parameter of count3() is 365.

If we run it...we get a big answer, as expected. It also takes quite a while!

You may not have realized that we soft-coded our program at all, but the whole point of functions is to soft-code programs!

Congrats on writing a program that is around 25 lines long!

Very Basic Datatypes

An integer is a basic datatype in Python. Basically, all variables with the datatype of int is an integer.

A string is another basic datatype, and it is a string of characters enclosed by quotes.

Why Are Datatypes So Important?

Let's say we wanted to make a program that would add 2 and 3. Some bogus code would be:

x="2" y="3" print(x+y)

If you ran this code, you would get 23. Why is that?

Well, here, x and y are strings. When you perform the addition operator to strings in Python, it concatenates the strings, giving 23.

The real code is:

x=2 y=3 print(x+y)

If you run this, you will get ![]() , which is correct.

, which is correct.

Here's another reason datatypes are important. Now, we will introduce the datatype called the floating point number, or float. A floating-point number is a number with a decimal point.

Let's go back to the IDLE. Type "0.1*10". The result is 1.0. Notice the decimal point.

Let's type something different. Type 0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1+0.1.

WHAT!?

You would have expected the answer to be 1, but it isn't 1. What happened?

Float approximation happened. Most (almost all) programming languages have a bad float approximation. That means that 1.0 can turn into 0.99999999999999 and 0.5 can turn into 0.49999999999999999993. That only happens with floats, so we should try to use floats as sparingly as possible.

Lists

A for loop iterates over a list. A list is a bunch of objects stored in one variable. (Hey! A list is a datatype!) For loops are highly related to lists.

Let's say we wanted to make a program to print all the items in a list.

We will first create the list, using the code:

myList = [1,4,6,8]

This is a list with four items: 1, 4, 6, and 8.

We must now print all elements of it with a for loop: