Difference between revisions of "Pascal's triangle"

(Added proof) |

|||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''Pascal's triangle''' is a triangle which contains the values from the [[binomial expansion]]; its various properties play a large role in [[combinatorics]]. | '''Pascal's triangle''' is a triangle which contains the values from the [[binomial expansion]]; its various properties play a large role in [[combinatorics]]. | ||

| Line 6: | Line 4: | ||

=== Binomial coefficients === | === Binomial coefficients === | ||

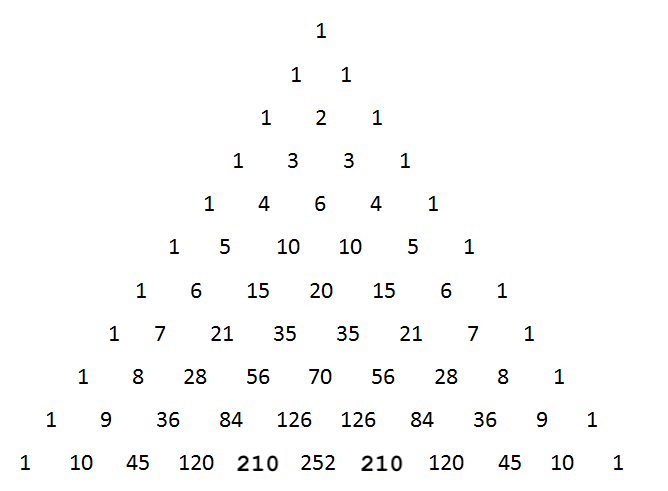

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Pascaltriangle.jpg|frame|right|110px|These are the first nine rows of Pascal's Triangle.]] Pascal's Triangle is defined such that the number in row <math>n</math> and column <math>k</math> is <math>{n\choose k}</math>. For this reason, [[mathematical convention|convention]] holds that both row numbers and column numbers start with 0. Thus, the apex of the triangle is row 0, and the first number in each row is column 0. As an example, the number in row 4, column 2 is <math>{4 \choose 2} = 6</math>. Pascal's Triangle thus can serve as a "look-up table" for binomial expansion values. Also, many of the characteristics of Pascal's Triangle are derived from [[combinatorial identities]]; for example, because <math>\sum_{k=0}^{n}{{n \choose k}}=2^n</math>, the sum of the values on row <math>n</math> of Pascal's Triangle is <math>2^n</math>. |

=== Sum of previous values === | === Sum of previous values === | ||

| − | One of the best known features of Pascal's Triangle is derived from the combinatorics identity <math>{n \choose k}+{n \choose k+1} = {n+1 \choose k+1}</math>. Thus, any number in the interior of Pascal's Triangle will be the sum of the two numbers appearing above it. For example, <math>{5 \choose 1}+{5 \choose 2} = 5 + 10 = 15 = {6 \choose 2}</math> | + | One of the best known features of Pascal's Triangle is derived from the combinatorics identity <math>{n \choose k}+{n \choose k+1} = {n+1 \choose k+1}</math>. Thus, any number in the interior of Pascal's Triangle will be the sum of the two numbers appearing above it. For example, <math>{5 \choose 1}+{5 \choose 2} = 5 + 10 = 15 = {6 \choose 2}</math>. This property allows the easy creation of the first few rows of Pascal's Triangle without having to calculate out each binomial expansion. |

=== Fibonacci numbers === | === Fibonacci numbers === | ||

| − | The [[Fibonacci sequence|Fibonacci numbers]] appear in Pascal's Triangle along the "shallow diagonals." That is, <math>{n \choose 0}+{n-1 \choose 1}+\cdots+{n-\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\rfloor \choose \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor} = F(n+1)</math>, where <math>F(n)</math> is the Fibonacci sequence. For example, <math>{6 \choose 0}+{5 \choose 1}+{4 \choose 2}+{3 \choose 3} = 1 + 5 + 6 + | + | The [[Fibonacci sequence|Fibonacci numbers]] appear in Pascal's Triangle along the "shallow diagonals." That is, <math>{n \choose 0}+{n-1 \choose 1}+\cdots+{n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor \choose \left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right \rfloor} = F(n+1)</math>, where <math>F(n)</math> is the Fibonacci sequence. For example, <math>{6 \choose 0}+{5 \choose 1}+{4 \choose 2}+{3 \choose 3} = 1 + 5 + 6 + 1 = 13 = F(7)</math>. A "shallow diagonal" is plotted in the diagram. |

| − | === Hockey- | + | === Hockey-Stick Identity === |

| − | The [[Hockey- | + | The [[Combinatorial identity#Hockey-Stick Identity|Hockey-Stick Identity]] states: |

| − | <math>{n \choose 0}+{n+1 \choose 1}+\cdots+{n+k \choose k} = {n+k+1 \choose k}</math>. Its name is due to the "hockey-stick" which appears when the numbers are plotted on Pascal's Triangle, as shown in the representation of the theorem | + | <math>{n \choose 0}+{n+1 \choose 1}+\cdots+{n+k \choose k} = {n+k+1 \choose k}</math>. Its name is due to the "hockey-stick" which appears when the numbers are plotted on Pascal's Triangle, as shown in the representation of the theorem below (where <math>n=2</math> and <math>k=3</math>). |

| + | |||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | int chew(int n,int r){ | ||

| + | int res=1; | ||

| + | for(int i=0;i<r;++i){ | ||

| + | res=quotient(res*(n-i),i+1); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | return res; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | for(int n=0;n<9;++n){ | ||

| + | for(int i=0;i<=n;++i){ | ||

| + | if((i==2 && n<6)||(i==3 && n==6)){ | ||

| + | if(n==6){label(string(chew(n,i)),(11+n/2-i,-n),p=red+2.5);} | ||

| + | else{label(string(chew(n,i)),(11+n/2-i,-n),p=blue+2);} | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | else{ | ||

| + | label(string(chew(n,i)),(11+n/2-i,-n)); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

=== Number Parity === | === Number Parity === | ||

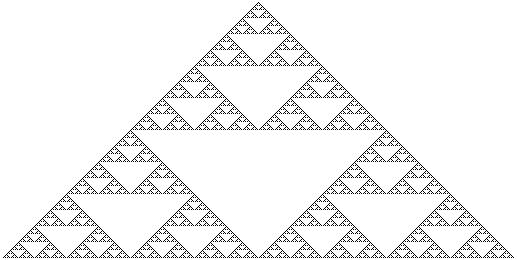

| − | Consider writing the row number <math>n</math> in [[base number | base]] two as <math>({n})_{10} = {(a_xa_{x-1} \cdots a_1a_0)}_2</math><math> = a_x 2^x+a_{x-1} 2^{x-1}+\cdots+a_1 2^1+a_0 2^0</math>. The number in the <math>k</math>th column of the <math>n</math>th row in Pascal's Triangle is [[odd integer | odd]] if and only if <math>k</math> can be expressed as the sum of some <math>a_i 2^i</math>. For example, <math>(9)_{10} = {(1001)}_{2} = 2^{3}+2^{0}</math>. Thus, the only 4 odd numbers in the 9th row will be in the <math>{(0000)}_{2} = 0</math>th, <math>{(0001)}_{2} = 2^0 = 1</math>st, <math>{(1000)}_{2} = 2^3 = 8</math>th, and <math>{(1001)}_{2} = 2^3+2^0 = 9</math>th columns. Additionally, marking each of these odd numbers in Pascal's Triangle creates a [[Sierpinski triangle]].[[Image:Sierpinski.jpg]] | + | Consider writing the row number <math>n</math> in [[base number | base]] two as <math>({n})_{10} = {(a_xa_{x-1} \cdots a_1a_0)}_2</math><math> = a_x 2^x+a_{x-1} 2^{x-1}+\cdots+a_1 2^1+a_0 2^0</math>. The number in the <math>k</math>th column of the <math>n</math>th row in Pascal's Triangle is [[odd integer | odd]] if and only if <math>k</math> can be expressed as the sum of some <math>a_i 2^i</math>. For example, <math>(9)_{10} = {(1001)}_{2} = 2^{3}+2^{0}</math>. Thus, the only 4 odd numbers in the 9th row will be in the <math>{(0000)}_{2} = 0</math>th, <math>{(0001)}_{2} = 2^0 = 1</math>st, <math>{(1000)}_{2} = 2^3 = 8</math>th, and <math>{(1001)}_{2} = 2^3+2^0 = 9</math>th columns. Additionally, marking each of these odd numbers in Pascal's Triangle creates a [[Sierpinski triangle]]. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Sierpinski.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Generalization ==== | ||

| + | This is a special case of Kummer's Theorem, which states that given a prime p and integers m,n, the highest power of p dividing <math>\binom{m}{n}</math> is the number of carries in adding <math>m-n</math> and n in base p. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Patterns and Properties of the Pascal's Triangle === | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Rows ==== | ||

| + | The zeroth row has a sum of <math> 1=2^0 </math>. The first row has a sum of <math> 2=2^1 </math>. The <math>n^{th} </math> row has a sum of <math> 2^n </math>, which means there are <math>2^n</math> ways to get to that row from the zeroth row. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Proof''': To find the number of ways to get to the <math>n^{th}</math> row of Pascal's Triangle, let's start with the zeroth row. There are <math>2</math> ways to get to the next row because there are <math>2</math> numbers in the first row. Now to get to the second row, we realize that starting from any number on the first row, we have two options to go to in the second row. This means we need to multiply the number of ways to get to the first row by <math>2</math>, which gives us <math>2 \cdot 2 = 2^2 = 4</math>. This pattern continues, so the number of ways to get to the <math>n^{th}</math> row of Pascal's Triangle is <math>2^n</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Diagonals === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 1st downward diagonal is a row of 1's, the 2nd downward diagonal on each side consists of the [[natural numbers]], the 3rd diagonal the [[triangular numbers]], and the 4th the [[pyramidal numbers]]. | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Latest revision as of 16:20, 3 January 2023

Pascal's triangle is a triangle which contains the values from the binomial expansion; its various properties play a large role in combinatorics.

Contents

Properties

Binomial coefficients

Pascal's Triangle is defined such that the number in row ![]() and column

and column ![]() is

is ![]() . For this reason, convention holds that both row numbers and column numbers start with 0. Thus, the apex of the triangle is row 0, and the first number in each row is column 0. As an example, the number in row 4, column 2 is

. For this reason, convention holds that both row numbers and column numbers start with 0. Thus, the apex of the triangle is row 0, and the first number in each row is column 0. As an example, the number in row 4, column 2 is  . Pascal's Triangle thus can serve as a "look-up table" for binomial expansion values. Also, many of the characteristics of Pascal's Triangle are derived from combinatorial identities; for example, because

. Pascal's Triangle thus can serve as a "look-up table" for binomial expansion values. Also, many of the characteristics of Pascal's Triangle are derived from combinatorial identities; for example, because  , the sum of the values on row

, the sum of the values on row ![]() of Pascal's Triangle is

of Pascal's Triangle is ![]() .

.

Sum of previous values

One of the best known features of Pascal's Triangle is derived from the combinatorics identity  . Thus, any number in the interior of Pascal's Triangle will be the sum of the two numbers appearing above it. For example,

. Thus, any number in the interior of Pascal's Triangle will be the sum of the two numbers appearing above it. For example,  . This property allows the easy creation of the first few rows of Pascal's Triangle without having to calculate out each binomial expansion.

. This property allows the easy creation of the first few rows of Pascal's Triangle without having to calculate out each binomial expansion.

Fibonacci numbers

The Fibonacci numbers appear in Pascal's Triangle along the "shallow diagonals." That is,  , where

, where ![]() is the Fibonacci sequence. For example,

is the Fibonacci sequence. For example,  . A "shallow diagonal" is plotted in the diagram.

. A "shallow diagonal" is plotted in the diagram.

Hockey-Stick Identity

The Hockey-Stick Identity states:

. Its name is due to the "hockey-stick" which appears when the numbers are plotted on Pascal's Triangle, as shown in the representation of the theorem below (where

. Its name is due to the "hockey-stick" which appears when the numbers are plotted on Pascal's Triangle, as shown in the representation of the theorem below (where ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

![[asy] int chew(int n,int r){ int res=1; for(int i=0;i<r;++i){ res=quotient(res*(n-i),i+1); } return res; } for(int n=0;n<9;++n){ for(int i=0;i<=n;++i){ if((i==2 && n<6)||(i==3 && n==6)){ if(n==6){label(string(chew(n,i)),(11+n/2-i,-n),p=red+2.5);} else{label(string(chew(n,i)),(11+n/2-i,-n),p=blue+2);} } else{ label(string(chew(n,i)),(11+n/2-i,-n)); } } } [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/1/5/f/15f56f8b93b4a5a45ce3644c2c13105f8423aa00.png)

Number Parity

Consider writing the row number ![]() in base two as

in base two as ![]()

![]() . The number in the

. The number in the ![]() th column of the

th column of the ![]() th row in Pascal's Triangle is odd if and only if

th row in Pascal's Triangle is odd if and only if ![]() can be expressed as the sum of some

can be expressed as the sum of some ![]() . For example,

. For example, ![]() . Thus, the only 4 odd numbers in the 9th row will be in the

. Thus, the only 4 odd numbers in the 9th row will be in the ![]() th,

th, ![]() st,

st, ![]() th, and

th, and ![]() th columns. Additionally, marking each of these odd numbers in Pascal's Triangle creates a Sierpinski triangle.

th columns. Additionally, marking each of these odd numbers in Pascal's Triangle creates a Sierpinski triangle.

Generalization

This is a special case of Kummer's Theorem, which states that given a prime p and integers m,n, the highest power of p dividing ![]() is the number of carries in adding

is the number of carries in adding ![]() and n in base p.

and n in base p.

Patterns and Properties of the Pascal's Triangle

Rows

The zeroth row has a sum of ![]() . The first row has a sum of

. The first row has a sum of ![]() . The

. The ![]() row has a sum of

row has a sum of ![]() , which means there are

, which means there are ![]() ways to get to that row from the zeroth row.

ways to get to that row from the zeroth row.

Proof: To find the number of ways to get to the ![]() row of Pascal's Triangle, let's start with the zeroth row. There are

row of Pascal's Triangle, let's start with the zeroth row. There are ![]() ways to get to the next row because there are

ways to get to the next row because there are ![]() numbers in the first row. Now to get to the second row, we realize that starting from any number on the first row, we have two options to go to in the second row. This means we need to multiply the number of ways to get to the first row by

numbers in the first row. Now to get to the second row, we realize that starting from any number on the first row, we have two options to go to in the second row. This means we need to multiply the number of ways to get to the first row by ![]() , which gives us

, which gives us ![]() . This pattern continues, so the number of ways to get to the

. This pattern continues, so the number of ways to get to the ![]() row of Pascal's Triangle is

row of Pascal's Triangle is ![]() .

.

Diagonals

The 1st downward diagonal is a row of 1's, the 2nd downward diagonal on each side consists of the natural numbers, the 3rd diagonal the triangular numbers, and the 4th the pyramidal numbers.